|

Paying Attention

Copyright © 2007 by Barry Spector. Copyright © 2007 by Barry Spector.

Barry Spector writes about American history and politics from the perspective of mythology and archetypal psychology. He is seeking a publisher for his book, Madness At The Gates Of The City: The Myth Of American Innocence. Barry is a regular performer at Great Night of Soul poetry events in the San Francisco Bay Area. He and his wife Maya present Oral Traditions Salons and facilitate an annual "Day of the Dead" grief ritual. Bay Area readers are encouraged to email him at shmoover@comcast.net to get on his mailing list for these events. Barry runs a furniture moving company, but he would rather move your soul.

Much spiritual and mystical literature speaks of the need for the individual to pay full attention, to be present moment to moment. Soul-work requires focusing one's awareness of both the outer and the inner worlds with a detached, witnessing perspective, even while, as Joseph Campbell wrote, participating in the joys and sorrows of the world. Paying attention (attention: from the Latin, "to stretch") inevitably forces the individual into the awareness of infinite complexity and mystery. Resisting the temptation to resolve the big questions of life into simple, black-white dualities and moralisms — the legacy of monotheistic thinking — we are called to hold the tension (from the same root, to stretch) of the opposites. Without being willing to pay attention and acknowledge that part of the self that is normally hidden from awareness, we run the eventual risk of experiencing a disruptive return of the repressed. This is the way of the indigenous, creative imagination: turning life's tragic contradictions and impossible choices into the images of art.

But what about a community? Is it necessary or even possible for an entire society to hold that kind of attention, if only for a brief but intense period of time? If so, it would need to evolve ways to acknowledge the presence of its own shadow. A community cannot enter a psychotherapeutic relationship; it can only approach an acceptance of the unconscious through communal ritual. In the case of a highly rational and structured society such as that of Classical Athens, the shadow is the unreasonable, violent and uncontrollable force of natural life. Like the ivy plant in a garden, it continually threatens to creep stealthily across the carefully contrived boundaries of the social role or mask — the persona — that we show to the world. But what about a community? Is it necessary or even possible for an entire society to hold that kind of attention, if only for a brief but intense period of time? If so, it would need to evolve ways to acknowledge the presence of its own shadow. A community cannot enter a psychotherapeutic relationship; it can only approach an acceptance of the unconscious through communal ritual. In the case of a highly rational and structured society such as that of Classical Athens, the shadow is the unreasonable, violent and uncontrollable force of natural life. Like the ivy plant in a garden, it continually threatens to creep stealthily across the carefully contrived boundaries of the social role or mask — the persona — that we show to the world.

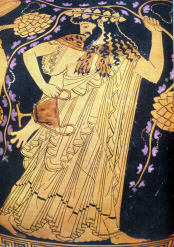

For the Athenians the mythic image that expressed the irrational, the paradoxical and the mysterious was Dionysus, the god of the extremes of both ecstasy and madness. In his inebriated yet exalted state, he could bring joyous celebration as well as the great art of tragic drama. He was paradox: the only god to suffer and die, and yet to always return. For a few centuries Greek myth and ritual struggled to hold the tension, the mystery and the tragedy of life that he represented. Classicist E. R. Dodds acknowledged that the rationalist elders of Athens "were deeply and imaginatively aware of the power, the wonder, and the peril of the Irrational."1

Ancient wisdom had told of the price that the psyche — and the community — paid for ignoring the mad god and his passions. Many of his myths told of the destructive vengeance he visited upon those mortals who denied the truth of reality — his reality. In story after story, Dionysus arrived from afar with his retinue of dancing maenads and drunken satyrs, only to be rejected by such mythic figures as Lykourgos, Minyas, Proetus, Eleuther, Perseus, and most famously in Thebes by Pentheus (in The Bacchae by Euripides.) And time after time, Dionysus punished the unbelievers or their kin with madness so severe that it caused them to unknowingly slaughter some of their own children. Consider the three daughters of King Proetus of Tiryns in the Peloponnesus. They refused to join Dionysus and his wild revels; in response he struck them mad. They infected the other women with their insanity, and all left their families. Some wandered as nymphomaniacs; others killed and ate their own children. One of the daughters died before the others were purified.

The Athenians themselves told an old story: once in the dim past they had not received the statue of Dionysus with appropriate respect when it was first brought to the city. Angered, the god had sent an affliction on the genitals of the men. They were cured only when they duly honored him by fashioning great phalluses for use in his worship. After that education in proper respect the Athenian Empire required its colonies to send phalluses (along with tribute) as part of the annual celebrations of the City Dionysia.

Scholars call these legends "myths of arrival," implying that they tell of the spread of a new cult.2 We, however, are looking for the archetypal implications. Why does the gentle and effeminate god of ecstasy arrive so often with such ferocity? Like alcohol itself, he loosens inhibitions. He was known as Lusios, the "Loosener." James Hillman points out that the word is connected to lysis, the last half of the word analysis, which means "loosening, setting free, deliverance, dissolution, collapse, breaking bonds and laws, and the final unraveling as of a plot in tragedy."3 A catalyst is an agent, chemical or otherwise, that precipitates a process or event, without being changed by the consequences.

What lies below the surface has great power because, like a diamond, it has been compressed. Is it not that, like all of the "Others" of the world, the god has experienced the shame of having been cast out of the city, beyond the pale, among the barbarians, into the underworld, to lick his wounds and nurse his resentment? Are we really surprised that when he is invoked unconsciously, passively, or literally (by consuming spirits!) he is as likely to bring rage as he is to bring ecstasy? It would seem that when he comes back — and he always does, like ivy — the psyche experiences his arrival as the violent return of the repressed. But it need not always be this way. Nor Hall comments on the story of the daughters of Proteus:

-

Their bodies become covered with white splotches, and they are set out upon the hills to wander like cows in heat. Only now are they fitting partners for the God in bull form. Had they joined the Dionysian company willingly (my italics), they would have enacted this state of wild abandon within a protective circle.4

Ritual, in order to retrieve a state of balance that has been lost, may involve — within such a protective circle — the symbolic enactment and emotional experience of our deepest conflicts and irreconcilable opposites, with the intention that such discord might not have to erupt — and disrupt — literally. The Athenian religious and political leaders were faced with the question of how to pay attention to Dionysus — something they would rather not have done. How could they consciously invite this mad, unreasonable god of vengeance and wild emotional extremes — the "Other" — into the center of the city in the hope that he wouldn't take vengeance? One way they accomplished this was in the annual productions of tragic drama in March, where the entire city endured the tension of holding irreconcilable opposites together, as enacted onstage in the Theater of Dionysus. Ritual, in order to retrieve a state of balance that has been lost, may involve — within such a protective circle — the symbolic enactment and emotional experience of our deepest conflicts and irreconcilable opposites, with the intention that such discord might not have to erupt — and disrupt — literally. The Athenian religious and political leaders were faced with the question of how to pay attention to Dionysus — something they would rather not have done. How could they consciously invite this mad, unreasonable god of vengeance and wild emotional extremes — the "Other" — into the center of the city in the hope that he wouldn't take vengeance? One way they accomplished this was in the annual productions of tragic drama in March, where the entire city endured the tension of holding irreconcilable opposites together, as enacted onstage in the Theater of Dionysus.

Another method was to celebrate an annual late winter (the previous month, in early- to mid-February) festival called the Anthesteria — the festival of flowers — during which the new wine was opened. The city invoked Dionysus "as a purifier, not as a destroyer," writes Charles Segal. The God arrived "bringing the life-enhancing benefits of viticulture and the drinking of wine."5

The Anthesteria was one of the earliest European all-souls' festivals, in which the citizens welcomed the spirits of the dead, and along with them, Dionysus, back into the city for three days of drinking and merry-making. But, difficult as it may seem to modern consciousness, historians tell us that the joy alternated with deep somberness, even grief. Apparently, the people retained a memory of the ancient knowledge that it was impossible to invoke one extreme of experience without also accepting the presence of its opposite. Dionysus, played by one of his priests, ceremonially returned from his annual sojourn in Persephone's palace in Hades. They towed him, wearing a bearded, two-faced mask, into the city on a "ship on wheels" which was crowned with vine tendrils. Images from those times show panthers pulling the cart. The citizens welcomed the god together with his wife Ariadne, the two of them returned from the sea, that universal symbol of the collective unconscious. We recall how Ariadne had helped save the hero Theseus from the Minotaur, the dreadful monster of the labyrinth; how Theseus had returned the favor by abandoning her on an island; and how Dionysus had saved her and married her. To celebrate their sacred marriage, Dionysus gave her a jeweled crown, which he later placed in the heavens as the constellation Corona Borealis.6

Dionysus is also the source of the tradition of wearing masks in these processions, as Walter Otto wrote: "Because it is his nature to appear suddenly and with overwhelming might before mankind, the mask serves as his symbol and his incarnation in cult... (the mask) is linked with the eternal enigmas of duality and paradox."7 The Greek word for mask was persona, and the mask reminded everyone of the untamed forces of nature that lay just below the surface of appearances. Dionysus is also the source of the tradition of wearing masks in these processions, as Walter Otto wrote: "Because it is his nature to appear suddenly and with overwhelming might before mankind, the mask serves as his symbol and his incarnation in cult... (the mask) is linked with the eternal enigmas of duality and paradox."7 The Greek word for mask was persona, and the mask reminded everyone of the untamed forces of nature that lay just below the surface of appearances.

Similar festivals were held in mid-winter in Egypt and Rome. In Later centuries Christian Europe celebrated carnival during this same season,8 despite the disapproval of the church, and to this day masked revelers often tow the carnival King and Queen through the streets, just like Dionysus and Ariadne, on a ship on wheels. Traditional European carnival was a time out of time, emphasizing both the liminal betwixt-and-between state as well as the cyclic nature of existence. It was a period of humor, paradox, wild behavior and a temporary inversion of the social order with a breaking of taboos that bordered on subversion. Anthropologist John Jervis writes that the people celebrated the body "... in all its messy materiality: eating, drinking, copulating, defecating, procreating, dying..."9 To an extent almost unimaginable today, entire communities participated — briefly — as equals, with little distinction between performers and audience, many of whom wore death masks. Amid the merriment, one can still observe the ancient theme of welcoming the spirits of the dead back to the world of the living for a few days.

But now, in the Christian context, the joy precedes the austerities of Lent, which is itself followed by more celebration. And the people invoke a different god of suffering and love — a spiritual god who is utterly disconnected from his dark, physical twin, a figure who remains in the underworld plotting his revenge. And in the Protestant and Moslem worlds, he is disconnected — unlike Dionysus — from his mother as well.

Indigenous people believed that the dead were always close by at the times of the greatest celebrations. The festivals of mid-winter, especially, looked forward to the annual restoration of the world that would come in springtime. But the elders taught that renewal would be unlikely unless due attention were paid to that which must die, as well as to those — like Dionysus — who had died and become ancestors.

Certainly in repressive and feudal systems the political and religious elites have often understood the importance of allowing the common people to let off a little steam for a few days once a year. Jervis notes that, "the symbolic inversion revealed the absurdity of a real one."10 Modern culture has long since literalized carnival to its "toxic mimic:" the secular, consumer-oriented spectacles of Mardi Gras, Las Vegas, "Spring Break" and the Superbowl. But even today, a festival called the Gynaekokracia ("rule of the women") is celebrated in the Greek town of Monoklissia in which the women and men trade their traditional roles for one day. Like all carnivals, it serves the two-fold purposes of releasing the tension produced by traditional repressive cultures and re-affirming their rules, revitalizing the social order by reenacting its conception.11 Travel writer Patricia Storace describes the scene: "The transvestism here is a social, even a political transvestism — the men are not just dressing like women, but being treated like women by women mocking men's behavior."12

But the original carnival, the festival of the Anthesteria was — or at least recalled as — something very significant from the more ancient past. Most important, for our purposes, the basilinna, the wife of the religious king of the city, or archon bassileus, engaged in a highly publicized, ritual copulation with Dionysus. The conventional scholarly explanation of this holiday is that, in addition to maintaining the social order, it celebrated and recapitulated the original marriage of Dionysus and Ariadne and was a fertility ritual intended to ensure good crops.

This may be accurate on a sociological level, but it is also undoubtedly true that many of the citizens were consciously re-enacting the hieros gamos,13 a mythic union that had its roots in the pre-patriarchal Minoan era. Why is this ritual marriage so meaningful? Karl Kerenyi wrote that just as Dionysus was the embodiment of zoe, "the archetypal image of indestructible life," so Ariadne was "the archetypal reality of the bestowal of soul, of what makes a living creature an individual." The union of this divine pair thus represented the "eternal passage of zoe into and through the genesis of living creatures."14 It was the sacred marriage of goddess and consort, or the inner king and queen who met each other in the sea of the unconscious. It was a reminder of the ultimate unity of opposites that lies behind the mask and the apparent dualities of the world.

The indigenous knowledge was still barely alive in classical Athens: the proximity of fertility and decomposition, of the goddess Persephone and her husband Hades (who was known as Ploutos, or "wealth") — and also of Dionysus in his many roles of divine child, mature initiator and, as the perpetual "Other," threat to the social order. The polytheistic imagination could still hold such paradox, even as the age of the rationalist philosophers approached. The indigenous knowledge was still barely alive in classical Athens: the proximity of fertility and decomposition, of the goddess Persephone and her husband Hades (who was known as Ploutos, or "wealth") — and also of Dionysus in his many roles of divine child, mature initiator and, as the perpetual "Other," threat to the social order. The polytheistic imagination could still hold such paradox, even as the age of the rationalist philosophers approached.

We cannot know what occurred when the queen met Dionysus, or what meaning the citizens saw in it. Whether she lay down with the king himself or a priest of Dionysus, or if either man was dressed and masked as the god, or whether their union was consummated literally, does not really concern us. The important thing, according to classicist Richard Seaford, is that there was an "invasion of the royal household by a publicly escorted stranger who symbolically destroys its potential autonomy by having sex with the king archon's wife."15 Dionysus Lusios — the "Loosener" — suddenly appeared at the head of a great procession, announcing his presence at the palace of the archon to claim the Queen for his own! And that night, all over Athens, men donned masks and impersonated the god at the doors of other men's wives. For one night, everyone ignored the normally rigid conventions of gender, class, fidelity and possessiveness. But soon after, in daylight, the citizens swept through the streets chasing the keres, the spirits of the dead, out of the city for another year.

Perhaps, just perhaps, we have here a partial record of an advanced urban civilization that recognized the absolute necessity of welcoming in the shadowy, wet, irrational, uncivilized stranger (xenos, the root of xenophobia, can mean both "stranger" and "guest") along with the spirits of all those who had died unreconciled and ungrieved. Perhaps the people hoped that their rituals might minimize the possibility of any violent eruption of the repressed energies that might topple the twin towers of religion and state. Perhaps they had reason to believe that, because of the ritual attention they paid to the Lord of the Darkness, there might not be an unintended, overwhelmingly destructive, literal return of the repressed, in the city or in their souls.

Clearly, there was a deep tension in Athenian life that could only be partially resolved by such institutions as the Anthesteria and other occasional opportunities for release from the rigid class and gender roles and the militaristic vigilance required to sustain an empire. Dionysus stood squarely at the center of this paradox, serving both the needs for release of the under-classes as well as pointing the way toward participation in the greater mysteries of the soul. And so, writes Arthur Evans, Dionysus represented the return of the repressed in several senses:

- ...return of the religious needs of the lower classes, return of the demands of the non-rational part of the self, and return of the (ancient) Minoan feeling for the living unity of nature. And so in return he threatened several repressors: the aristocracy of well-to-do male citizens, the domination of intellect over emotion, the alienated ethos of the city-state.16

Perhaps the subtle balance between citizen, psyche and city — the world's first experiment with democracy — could not have been expected to survive for long in such a world of slavery, misogyny and almost constant warfare. Eventually the repressed would return in the form of barbarians from without as well as demons from within. But the communal ritual of invoking and welcoming the spirits of madness, ancestry and the irrational remains an alternative, imaginative model for a modern culture that denies its own capacity for violence. Perhaps the subtle balance between citizen, psyche and city — the world's first experiment with democracy — could not have been expected to survive for long in such a world of slavery, misogyny and almost constant warfare. Eventually the repressed would return in the form of barbarians from without as well as demons from within. But the communal ritual of invoking and welcoming the spirits of madness, ancestry and the irrational remains an alternative, imaginative model for a modern culture that denies its own capacity for violence.

Reviving such festivals in all their paradox of chaotic ecstasy mixed with deep sadness — holding the tension of the opposites — could be a first step in drawing back the projection of the Other from gays, women, Muslims and people of color. Finally, paying attention to Dionysus could be a step in awakening America from its four centuries-long fantasy of innocence.

Notes:

- Dodds, E.R., The Greeks and the Irrational (Univ. of California Press, 1951), p. 254

- Kerenyi, Carl, Dionysus, Archetypal Image of Indestructible Life (Princeton Univ. Press, 1976), p. 175

- Hillman, James,"Dionysos In Jung's Writing," in Hillman, ed, Facing The Gods (Dallas, Spring Pubs.), p. 162

- Hall, Nor, Those Women (Dallas: Spring Publications, 1988), p. 31

- Segal, Charles, Dionysian Poetics (Princeton Univ. Press, 1982, 1997), p. 350

- Harrod, James, "Dionysos and the Muses," Spring 70 (Spring, 2004), p. 205-225

- Otto, Walter, Dionysus (Indiana Univ. Press, 1965), p. 90-91

- Orloff, Alexander, Carnival: Myth and Cult, (Worgl, Austria, Perlinger, 1981)

- Jervis, John, Transgressing The Modern (Oxford: Blackwell, 1999), p. 18

- Jervis, John, Transgressing The Modern, p. 21

- Girard, René, Violence and the Sacred (Johns Hopkins Univ. Press, 1972), p.10

- Storace, Patricia, Dinner With Persephone, Travels In Greece (NY: Vintage, 1996), p. 236

- Burkert, Walter, Greek Religion (Harvard Univ. Press, 1985), p.239

- Kerenyi, Dionysus, p. 124-5

- Seaford, Richard, "Dionysus As Destroyer Of The Household," in Masks of Dionysus (T.H.Carpenter and C.A. Faraone, eds.), p. 135

- Evans, Arthur, The God of Ecstasy (NY: St. Martin's Press, 1988), p. 61

Return to Mythic Passages Menu

Subscribe to the Mythic Passages e-magazine

|