|

Hephaestus: Sacred Fire in the Wound

© 2007 Wilhelm Oosthuizen, used by permission

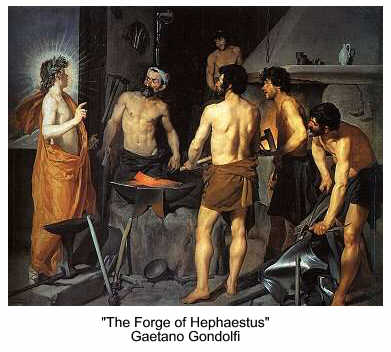

[Images: "Forge of Hephaestus" by Gaetano Gondalfi; "Thetis Receives Achilles Armor" by Anton Van Dyck ]

Within the context of this analysis, the archetypal motifs of the mother, the father, the abandoned child, and the wounded creative outsider, underscored by secrecy, herald the birth of Hephaestus. He is wounded at birth by his voraciously ambitious mother, Hera, who is disgusted by her son's physical deformity and ugliness. Claiming her son as an extension of herself, his imperfections cast a long shadow on her aspirations to godly perfection to prove herself superior to her husband and brother, Zeus. What lies at the root of the rejection of her son is a spirit of fierce competition in a marriage fueled by the tyranny of her aspiration to unattainable power (Homer Iliad I. 673-711). Within the context of this analysis, the archetypal motifs of the mother, the father, the abandoned child, and the wounded creative outsider, underscored by secrecy, herald the birth of Hephaestus. He is wounded at birth by his voraciously ambitious mother, Hera, who is disgusted by her son's physical deformity and ugliness. Claiming her son as an extension of herself, his imperfections cast a long shadow on her aspirations to godly perfection to prove herself superior to her husband and brother, Zeus. What lies at the root of the rejection of her son is a spirit of fierce competition in a marriage fueled by the tyranny of her aspiration to unattainable power (Homer Iliad I. 673-711).

Hephaestus's birth is shrouded in secrecy that is compounded by poor timing " ... because it occurred during the three hundred years in which Hera's relationship with Zeus was secret" (Kerényi 155). He speaks of his misbegetting and subsequent wounding when he laments: "I am not to blame for this nor is anyone else except both my parents who I wish had never begotten me" (Morford 127). Hera refuses to acknowledge her son as a being in his own right when she announces that he " ... was weak among all the gods, and his foot was shriveled, why it was a disgrace to me, a shame in heaven, so I took him in my own hands and threw him out into the deep sea" (Boer 168-69). With his mother's determined efforts that " ... had sought to keep his misbegetting secret " (Kerényi 155), he becomes a wounded outsider.

With the collision between Hera, who represents the feminine principle as an expression of the Mother archetype, and Zeus, who exemplifies the masculine principle as the Father archetype, the birth of the child is an unacceptable truth that becomes the tragic casualty of the hubristic relationship between two primary archetypal powers in the stand-off of duality. In another version of the story Hephaestus reminds his mother of how his father " ... on another occasion when I was eager to defend you ... grabbed me by the feet and hurled me from the divine threshold" (Morford 127). Thus, in that version it is as though Hephaestus' wound is inflicted by the masculine principle when he speaks out in defense of the feminine. Whether " ... Hephaestus is lame because he is thrown out of Olympus, or he is thrown out of Olympus because he is lame" (Gantz 75), his wounds are inflicted on separate occasions by either the feminine or the masculine principle, not because of who he is, but in response to his physical appearance that mirrors to others their own archetypal shadows. If patriarchy is understood as the forced submission of others with deliberate intent to exert power over the other, then both Hera and Zeus as the feminine and masculine archetypes respectively, demonstrate that regardless of gender, the violent expression of patriarchal values are not partial to either. With the collision between Hera, who represents the feminine principle as an expression of the Mother archetype, and Zeus, who exemplifies the masculine principle as the Father archetype, the birth of the child is an unacceptable truth that becomes the tragic casualty of the hubristic relationship between two primary archetypal powers in the stand-off of duality. In another version of the story Hephaestus reminds his mother of how his father " ... on another occasion when I was eager to defend you ... grabbed me by the feet and hurled me from the divine threshold" (Morford 127). Thus, in that version it is as though Hephaestus' wound is inflicted by the masculine principle when he speaks out in defense of the feminine. Whether " ... Hephaestus is lame because he is thrown out of Olympus, or he is thrown out of Olympus because he is lame" (Gantz 75), his wounds are inflicted on separate occasions by either the feminine or the masculine principle, not because of who he is, but in response to his physical appearance that mirrors to others their own archetypal shadows. If patriarchy is understood as the forced submission of others with deliberate intent to exert power over the other, then both Hera and Zeus as the feminine and masculine archetypes respectively, demonstrate that regardless of gender, the violent expression of patriarchal values are not partial to either.

Born of the collision of the Father and Mother archetypes, a third thing, the Child archetype, comes into being. Prominent elements of the child archetype as depicted in the story of Hephaestus are abandonment and wounding. His lameness is not his wound, but it is Hera's violent reaction to his lameness, and his distant, uncaring father's similar response to his advocacy of his mother that inflict the wounds.

Immense creative potential is blindly rejected by both parents who are myopically entangled with their fixed agendas. If from a Jungian depth psychological perspective the conniving Hera and Zeus represent aspects of the conscious mind, " ... that knows nothing beyond the opposites and, as a result, has no knowledge of the thing that unites them" (Jung, CW 9i: 285), then their surprising and unwanted creation brings into view the unconscious psychic process wherein as Jung says, " ... out of this collision of opposites the unconscious psyche always creates a third thing of an irrational nature, which the conscious mind neither expects nor understands" (CW 9i: 285). The psycho-spiritual tearing apart of Hephaestus by either or both of his parents augurs the presence of a greater transcendent divine principle, since " ... physical handicap, which combines the themes of sparagmos [tearing to pieces] and ritual death, is often the price of unusual wisdom or power, as it is in the figure of the crippled smith Weyland or Hephaestus ... " (Frye 193).

The wounded Hephaestus is completely separated from his origin of lofty Mount Olympus where quarrelsome gods go about their daily business. The severity of his severance from his ancestral roots is almost fatal as he falls " ... on Lemnos, almost unbreathing ... " (Kerényi 156). From an archetypal perspective, however, Jung says that " ... the 'child' is endowed with superior powers and, despite all dangers, will unexpectedly pull through" (CW 9i: 289) — and so he does. He survives and consequently thrives, since from an archetypal and psychological point of view, Jung observes "that though the child may be "insignificant," unknown, "a mere child," he is also divine" (CW 9i: 289). The wounded Hephaestus is completely separated from his origin of lofty Mount Olympus where quarrelsome gods go about their daily business. The severity of his severance from his ancestral roots is almost fatal as he falls " ... on Lemnos, almost unbreathing ... " (Kerényi 156). From an archetypal perspective, however, Jung says that " ... the 'child' is endowed with superior powers and, despite all dangers, will unexpectedly pull through" (CW 9i: 289) — and so he does. He survives and consequently thrives, since from an archetypal and psychological point of view, Jung observes "that though the child may be "insignificant," unknown, "a mere child," he is also divine" (CW 9i: 289).

The locations of the initial healing of his wounds are far removed from the original circumstances and environment where the wounds were inflicted. When he is found either by " ... Thetis, with her silver feet" (Boer 169) when Hera throws him into the sea, or, in Hephaestus's own words tells of how Zeus " ... seized my foot, he hurled me off the tremendous threshold ... down I plunged on Lemnos, little breath left in me" (Homer Iliad I.712-15), the life-threatening scope of his abandonment is evident. But a greater scope of power inherent in the archetypal life of the child assimilates the dimensions of his wound into its own womb of healing, wherein the conception of a second birth takes place. This second birth, as an aspect of individuation, is rooted in the secret depths of the ocean, or on the isolated island of Lemnos. There Thetis and Eurynome, or the Sintians respectively, facilitate a new beginning for the wounded Hephaestus. It is as though the second birth is an expression of "the urge and compulsion to self-realization [that] is a law of nature and thus of invincible power, even though its effect, at the start, is insignificant and improbable" (Jung, CW 9i: 289).

The acutely wounded, cast-out Hephaestus initially plunges into the dark ocean. Or on another occasion he recalls how " ... .when the sun went down, down I plunged on Lemnos ... " (Homer Iliad I. 714-15). Jung speaks of the relevant darkness or twilight in relation to the child archetype when he says: "The phenomenology of the "child's" birth always points back to an original psychological state of non-recognition, i.e., of darkness or twilight ... " (CW 9i: 290). Within darkness or twilight the sea-goddesses Thetis and Eurynome, or the Sintains, secretly come to the infant's rescue and nurture him back to life — in Hephaestus' own words: " ... no one knew. Not a single god or mortal, only Thetis and Eurynome knew — they saved me" (Homer Iliad 18. 472-73). Far removed from the battle between his parents, the wounded abandoned child points the symbolic way to the archetypal alchemical dissolution of the conflict, since "the conflict is not to be overcome by the conscious mind remaining caught between the opposites and for this very reason it needs a symbol to point out the necessity of detaching itself from its origins" (Jung, CW 9i: 287).

The silver feet of Thetis reflect her attributes of swiftness and unfettered mobility when her urgent departure with the gifts of armor for Achilles from Hephaestus' residence, is recounted: " ... down she flashed like a hawk from snowy Mount Olympus bearing the brilliant gear, the god of fire's gift" (Homer Iliad I. 719-20). Thetis acts as a guide to lead Hephaestus beyond his physical affliction to the depths of his authentic power from where he creatively affects the material world. The contrast between the silver feet of the sea-goddess, Thetis, and the deformed feet of Hephaestus, hints at the consequent healing transformation of Hephaestus's affliction from disability to the development and ultimate full expression of his creative and artistic genius. It is as though Thetis points Hephaestus in the direction of his true ground of being that is deeply seated in the terrestrial fire of his being. Not until he is able to tap into his spiritual ground of being is he able to transcend his physical afflictions. It is the spiritual fire that burns within his deepest, secret recesses that transforms what is crude and inert into brilliant beauty. The nearly fatal wound sets free within itself a sacred fire that creates and heals.

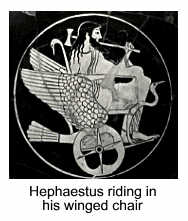

With the help of Thetis and the Sintians, Hephaestus transcends his physical disabilities of lameness and ugliness, beyond which he expresses his authentic power through the alchemical craft of the divine blacksmith. Through the art of the blacksmith, he sheds light on that which lies concealed under his superficial ugliness and physical deformity — the beauty and power of his divinity. Through the reflective light of his creative genius as a divine artisan, he makes visible about himself what others are blind to. Not only does his genius reflect his hidden beauty and strength outwardly, but serves to remind others of their own.

Within the dark, fertile soil of his involuntary introversion, the kernel of his power sprouts. On the spiritual-creative plane his mastery blossoms into brilliant beauty. His foundation, of which his feet are symbolic, is transformed from a wobbly base into an autonomous foundation from where he executes his craft.

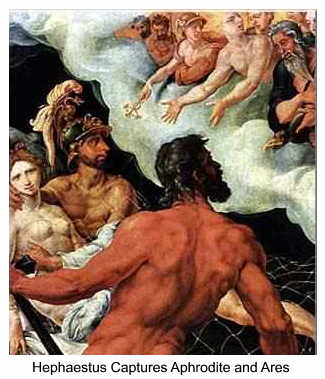

He is rejected by fixed reason as it is expressed by the masculine Zeus or the feminine Hera. He is welcomed by the sea-goddess, " ... Thetis of flowing robes ... " (Homer Iliad 18. 450) who conveys a sense of fluidity and with her " ... glistening feet ... " (Homer Iliad 18. 445), a sense of swiftly moving intuition. On Lemnos he is welcomed by the Sintians who are regarded as barbarians, representing that which is crude or undeveloped. With the intense alchemical heat of Spirit, base elements are transformed into exquisite beauty and the lowly location of his injury is elevated to " ... the well-built citadel of Lemnos, which of all lands was by far the most dear to him" (Morford 127). Once he is able to access his true power, he renders powerless the very things and people who, as a child, left him helpless. He captures Ares and Aphrodite in his invisible net, and renders his mother powerless on the very symbol of her power: the golden throne that Hephaestus had delivered to her as a gift.

Concealed within the tragedy lies humor, and within that humor, for those who wish to know, is a mirror that reflects truth. When Hephaestus hobbles amidst the amused gods, he gives expression to the archetype of the Court Jester who fills the gods' and goddesses' cups with nectar. His awkward movement is a source of amusement " ... as unquenchable laughter rose up among the blessed gods as they saw Hephaestus bustling about the house ... " (Morford 126). Crippled evidence — in the shape of Hephaestus that is the outcome of the battle of the sexes — escapes the awareness of the gods and goddesses: they pay no attention to the distorted movement born from the war of rejection by the feminine of the masculine, or vice versa.

The hubristic, seemingly sure-footed gods and goddesses fail to see, let alone heed, the warning inherent in the deeper meaning of Hephaestus' lameness. The crippled relationship between the colliding dysfunctional masculine and feminine principles is symbolically depicted by Hephaestus's misshapen feet and ugliness. The wounding takes place on a fundamental level, and thus distorts and delays overall mobility. The healing of the wound lies in deriving a deeper, concealed meaning from the essential elements that comprise the wound. Within the meaning extracted from the wound, immense creative and healing powers flow.

Both Zeus and Hera on Mount Olympus attempt to foster a secret relationship. Unbeknownst to them, their secret gives birth to its own kind that consequently and temporarily matches and arrests their power. The surprising revelatory appearance of the third thing, the child Hephaestus, is experienced as a premature annoyance they deny through his rejection. Out of sight and out of mind, however, does not prevent their secret creation from developing into its own powerful expression.

Once Hephaestus captures in his invisible net his wife Aphrodite with her secret lover Ares, he is able to capture the gods' attention. That which initially he had been vulnerable to out of lack — his distorted mobility and lack of beauty — he is now able to capture fully and, in their arrested state, bring into full view for all to see. He brings to light secrets when the anguished Hephaestus cries out " ... in a loud and terrible voice to all the gods: 'Father Zeus and you other blessed gods who live forever, come here so that you may see something that is laughable and cruel ...' " (Kerényi 127). Whereas Hephaestus had been the object of cruel laughter, he is able to deflect cruel humor by bringing to light greater truths or lies. Hephaestus becomes powerful because he recognizes his own power. His awareness of his innate power is what makes him powerful. The expression of his power stands firm, regardless of its acknowledgment or rejection by others. Once Hephaestus captures in his invisible net his wife Aphrodite with her secret lover Ares, he is able to capture the gods' attention. That which initially he had been vulnerable to out of lack — his distorted mobility and lack of beauty — he is now able to capture fully and, in their arrested state, bring into full view for all to see. He brings to light secrets when the anguished Hephaestus cries out " ... in a loud and terrible voice to all the gods: 'Father Zeus and you other blessed gods who live forever, come here so that you may see something that is laughable and cruel ...' " (Kerényi 127). Whereas Hephaestus had been the object of cruel laughter, he is able to deflect cruel humor by bringing to light greater truths or lies. Hephaestus becomes powerful because he recognizes his own power. His awareness of his innate power is what makes him powerful. The expression of his power stands firm, regardless of its acknowledgment or rejection by others.

Inherent in his fully-fledged creative power is also the power to bind, and within the power to bind, is the power of choice. Hephaestus is faced with the choice to release Aphrodite and Ares from his net, or to keep them captive. If he chooses to keep them captive, he would remain captured by his own creation. Seeing the two secret lovers arrested in his bed then serves as a perpetual reminder of his heartache. By keeping Aphrodite and Ares captive, Hephaestus binds himself to the painful reminder of the superficial beauty and outer mobility he lacks. The choice he faces is to release his captives, thereby liberating himself from painful past memories and reminders, or to perpetually relive his painful history until such time as he releases those who remind him of his imperfections. Should he decide to release his attachment to his history, then he would be able to return to present time and continue to live a highly creative life in service to all dimensions of life. His service to the gods and humans spreads beauty and comfort over whomever he serves or whoever approaches him for help. If he keeps Aphrodite and Ares captive, he would deprive others of his much needed service.

Hephaestus agrees to release Aphrodite and Ares when Poseidon promises compensation for the release of the captives. Poseidon, who is the regent of the ocean, is instrumental in Hephaestus's choice to release the lovers from captivity. In one of the versions, Aphrodite is returned to Hephaestus on his return to Mount Olympus, as if to imply that once one releases the need to possess something or someone, if one is truly meant to have it, it will become available on its own accord.

After the release of Aphrodite and Ares from his invisible net, Hephaestus re-enforces the most challenging and binding tie with his wounded past when he delivers to his mother a golden throne as a gift whereupon she " ... was suddenly bound with invisible chains" (Kerényi 157). Whereas the goddesses " ... in their modesty stayed at home one and all" (Morford 127), with the embarrassing situation of the captivity of Aphrodite and Ares, with Hera captive on her throne, none of the gods and goddesses are able to ignore the power of Hephaestus, since " ... none could release her and there was great consternation amongst the gods" (Kerényi 157).

He faces what is probably his most difficult choice: if he lets go of his need for revenge, he has to return to Mount Olympus to release his mother from captivity, and consequently take his rightful place amongst the gods. He has to return to his unhappy place of birth and the sources of his initial wound: Hera and Zeus. Instead of insisting " ... stubbornly that he had no mother" (Kerényi 157) and thus denying the existence of his primal wound, he has to forgive her and thereby release himself from ties that bind. But his reply to the Olympian gods and goddesses that " ... he had no mother" (Kerényi 157) implies that, in spite of his mother's rejection of him, both are still psychically tightly bound together — regardless of distance, he is not able to extricate himself of his own volition from his past relationship with her.

At the time " ... that the council of the gods all were silent and did not know how Hephaest(u)s could be brought to Olympus" (Kerényi 157), a solution appears in the person of Dionysus, whom Hillman points out was also called " ... Lysios, the loosener" (Hilllman 77). Drunk, under the loosening influence of Dionysus' wine, Hephaestus reluctantly returns to the place and people of his wounding. Once on Mount Olympus, Hephaestus sets himself and his mother free from the binding ties of resentment whereafter he takes his rightful place amongst the divine gods. Hera remains firm in her attachment to her fixed ideas about power and perfection, (and) thus fails to realize that "identity does not make consciousness possible; it is only separation, detachment, and agonizing confrontation through opposition that produce consciousness and insight" (Jung CW 9i: 289).

Insisting on strengthening her immutable stance on power, Hera calls upon Earth, Heaven, and the Titan gods to give her " ... a child separate from Zeus, and yet one who isn't any weaker than him in strength" (Boer 170). She says: "In fact, make him stronger than Zeus ... " (170). The powers she implores get to work to grant her wish and at the allotted time " ... she bore something that didn't resemble the gods, or humans, at all: she bore the dreaded, the cruel, Typhaon, a sorrow for mankind" (171).

The poets leave it up to the reader's imagination to give free reign to how Hephaestus' life continues after he released Hera from her throne. I cherish the idea that Hephaestus continues to spread joy and beauty with his creative genius, inspired by Charis, " ... lithe and lovely in all her glittering headdress, the Grace the illustrious crippled Smith had married" (Homer Iliad 18. 447-48) whilst they continue to live joyfully in " ... Hephaestus' house, indestructible, bright as stars, shining among the gods, built of bronze by the crippled Smith with his own hands" (431-33).

Works Cited

- Boer, Charles, trans. The Homeric Hymns. Putnam, Connecticut: Spring, 1970.

- Eliade, Mircea. The Forge and the Crucible: The Origins and Structure of Alchemy. Trans. Stephen Corrin. 1962. New York: Harper Torchbooks-Harper, 1971.

- Frye, Northrop. Anatomy of Criticism: Four Essays. 1957. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1971.

- Gantz, Timothy. Early Greek Myth: A Guide to Literary and Artistic Sources. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1993.

- Hesiod. The Works and Days, Theogony, The Shield of Herakles. Trans. Richmond Lattimore. 1959. Ann Arbor Paperbacks — University of Michigan Press, 1991.

- Hillman, James, ed. "Hephaistos: A Pattern of Introversion." Facing the Gods. Dallas, Texas: Spring, 1980.

- Homer. The Iliad. Trans. Robert Fagles. New York: Penguin Classics, 1990.

- Homer. The Odyssey. Trans. Robert Fagles. New York: Penguin Classics, 1996.

- Janik, Vicki K., ed. "Hephaestus, Hermes, and Prometheus: Jesters to the Gods." Fools and Jesters in Literature, Art and History: A Bibliographical Sourcebook. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood, 1998.

- Jung, Carl Gustav. "The Psychology of the Child Archetype." Trans. R.F.C. Hull. The Collected Works of C.G. Jung. Vol. 9i. Bollingen Series 20. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1959. 259-305.

- Kerényi, C. The Gods of the Greeks. Ed. Joseph Campbell. London: Thames, 1951.

- Morford, Mark P.O., and Robert J. Lenardon. Classical Mythology. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Pagan, Isabelle M. From Pioneer to Poet or The Twelve Great Gates: An Expansion of the Signs of the Zodiac Analysed. 5th ed. London: Theosophical Publishing House, 1969.

- Stroud, Joanne H., ed. "Hephaistos" The Olympians: Ancient Deities as Archetypes. New York: Continuum, 1995.

Wilhelm Oosthuizen was born in Mpumalanga, South Africa, where he lived until he immigrated to the USA in 1992. Shortly after his arrival, he continued with his career as a medical/surgical traveling nurse followed by work as a hospice nurse. Some of his primary interests include: music, mysticism, intuition, film, and global humanitarian and ecological concerns. Wilhelm is currently enrolled in the MA/PhD Program in Mythological Studies with an emphasis on Depth Psychology at Pacifica Graduate Institute in California where he currently resides. Wilhelm Oosthuizen was born in Mpumalanga, South Africa, where he lived until he immigrated to the USA in 1992. Shortly after his arrival, he continued with his career as a medical/surgical traveling nurse followed by work as a hospice nurse. Some of his primary interests include: music, mysticism, intuition, film, and global humanitarian and ecological concerns. Wilhelm is currently enrolled in the MA/PhD Program in Mythological Studies with an emphasis on Depth Psychology at Pacifica Graduate Institute in California where he currently resides.

Return to Passages Menu

Subscribe to the Passages e-zine

|