|

A Clockwork Pattern:

A Clockwork Pattern:

Rites of Passage in Stanley Kubrick's

"A Clockwork Orange"

by Gershon Reiter

What would Arnold van Gennep, the Belgian anthropologist who coined the term rite of passage, have to say about Stanley Kubrick's A Clockwork Orange? What would he make of the disturbing movie that Kubrick called a "psychological myth"? Surely he would notice that the movie follows the three-part pattern that he had discerned in the initiation ceremonies of indigenous peoples. Perhaps he would see it as reflecting modern man's misusing these ceremonial rites, turning them into social events bereft of spirit, ceremonies more clockwork than rites. Were he alive at the time of Clockwork's release in 1971, von Gennep would no doubt appreciate Kubrick's playing "Pomp and Circumstance" in the ceremony where Alex, the movie's hero, graduates from prisoner to patient.

All things considered, A Clockwork Orange presents a cynical and highly entertaining picture of von Gennep's three-part pattern of transformation. Like an oracle, Kubrick's futuristic movie foretells what happens when there are no meaningful rites of passage to accompany the changes from one phase of life to another. That the movie is divided into the three parts that make up van Gennep's rite of passage is suggested right from the start by the three consecutive colors that take up the whole screen. As the red, blue and reddish orange suggest, by the end of the movie Alex is not the same person he was at the beginning. He undergoes a transformation through the three stages of separation, initiation and return. Kubrick underscores the three stages by opening each of the movie's first three scenes with identical shots, the camera pulling away from a closeup to reveal each scene's wider setting.

Ironically enough, Kubrick has spoken out against what he sees as the problem with the three-part movie. "The problem with movies is that since the talkies the film industry has historically been conservative and word-oriented. The three-act play has been the model. It's time to abandon the conventional view of the movie as an extension of the three-act play."1 Putting his money where his movie is, Kubrick divides each of Clockwork's three rite of passage parts in two. He forms six parts, six distinct "stations" in the hero's misadventures, making Alex's story a fable of man's six stations in this "stinking world," from unrepressed infancy through growing repression to death and resurrection.

1) Unconscious Infancy:

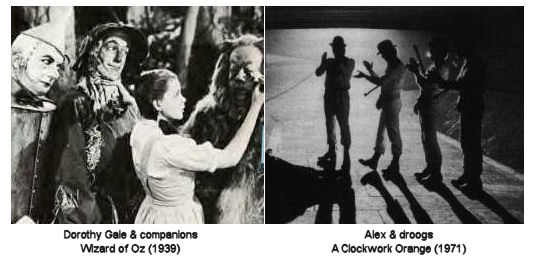

Evoking the first station of unconscious infancy, the movie opens in the maternal womb of the Korova Milk Bar, which offers many flavors of mother's moloko, man's primal source of pleasure — sucking "milk plus" from the mother's breast to gratify his oral needs. This is the hero Alex before the agents of repression start working on his "gulliver." The opening image, of Alex staring menacingly into the camera, at us, can also be read as his staring blankly into space, suggesting that what follows are his thoughts and fantasies, the works of his unconscious. Where else but in the unconscious does one have unbridled freedom to carry out every desire, where the pleasure principle reigns supreme? Alex's opening words, "There was me," are not unlike the words of a patient recounting his (unconscious) dream to a therapist, just as he relates his dream to the woman psychiatrist at the movie's last station. Moreover, Alex's "three droogs" recall the three companions in Dorothy Gale's unconscious dream-journey, suggesting that his is one as well.

The unconscious is further suggested in two of the three acts of violence that make up the first station where, not unlike Oedipus, Alex's ultra-violence is directed against the father. In his own words, "One thing I could never stand was to see a filthy, dirty old drunkie howling away at the filthy songs of his fathers." These words express Alex's unconscious aggression against his impotent father, which may explain his unruliness, to say the least. The aggression towards the father comes up again when the "travelers of the night playing Hogs of the Road," agents of the unconscious (moving like the apes in 2001: A Space Odyssey), unleash their ultra-violence on "home." Alex not only cripples the "sophisto," the logo, who shares his name, he rapes his woman in red, the same color of the getup his mother wears when visiting him in the hospital.

This unbridled freedom, however, does not last forever. Already police sirens, agents of repression, of "law and order," are heard in the background. That the station of unconscious infancy is coming to an end is signaled by Alex's own words. "And what I needed now to give it the perfect ending was a bit of the old Ludwig van," the same music that ends the movie.

2) Elementary School:

The second station, the "elementary school," starts the very next morning, when Alex, whose parents are powerless to make him go to school, encounters his first act of repression. In this phallic stage, if to go by the many phalluses that come up, Alex is warned by Mr. Deltoid, the truant officer who aims a blow at his genitals (the same spot where Alex kicked the writer the night before), "to keep your handsome young proboscis out of the dirt." But the arrogant Alex does not heed his warnings. He invites the two girls who suck promiscuously on proboscis-shaped popsicles to "hear angel trumpets and devil trombones."

That same day, after the three droogs' failed insurrection (the sons ganging up on the father), Georgie informs Alex, "Brother, you think and talk sometimes like a little child. Tonight we pull a man-sized crast." Come night, as the "scoundrels and rogues of the night about," agents of the unconscious, the four parade their "man-sized" phalluses. As the man of the lot, it is Alex, in what is clearly a symbolic act, who literally uses the proboscis to murder the Cat Woman who attacks him with a bust of Beethoven. But as the three droogs teach Alex by betrayal, he is too big for his britches.

At the police station, the first station of repression, where he is called "little Alex" and "boy," Alex is informed by Deltoid, "It's the end of the line," thus ending the second station just as he had opened it.

3) High School:

The third (high-school) station finds Alex in prison, where his former unbridled freedom is curtailed, where his identity is replaced by a serial number. "This is the real weepy and tragic part of the story beginning," Alex informs us over three aerial shots of the prison. Like a school boy who is put through the repressive mechanism of public education, Alex can only fantasize about what he formerly acted out. Though incarcerated, Alex remains the initiator of his fortune. He uses his "gulliver," which formerly gave him pain, to figure out what it takes to get out. To the tune of "Pomp and Circumstances," a traditional part of many high school graduation ceremonies, Alex cunningly graduates to the university, the fourth station, where his "gulliver" is to undergo a treatment of ultra-violent repression, where he is "transformed out of all recognition."

4) University:

Changing from prisoner to patient, Alex is transferred as a package, signed away in three copies and received by three signatures, with receipt and all. The fact that he has not been successfully repressed by prison is demonstrated by the way he jumps to attention before the hospital's reception desk. Despite the prison guard's warning to Alex's new repressor, "A right brutal bastard he has been, and will be again," the doctor is confident of his means of repression. "I think we can manage things."

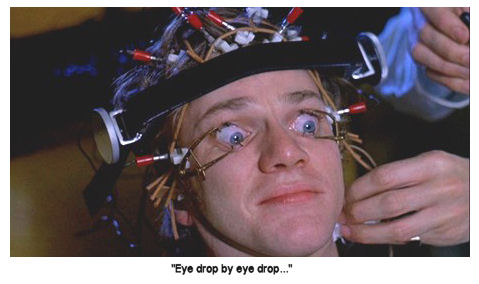

Instead of "milk plus" that in better days had released his dark desires, his unconscious, Alex is injected a serum that renders him vulnerable to repression. This station of repression is a first for Alex. Where in prison he experienced mostly physical suppression, at the hospital he undergoes mental repression, achieved primarily through cinematic means. "Where I was taken to, brothers, was like no cine I ever viddied before." The images he is forced to watch on the screen recall his former acts of unbridled aggression, his unrepressed violence. Eye drop by eye drop, Alex feels increasingly nauseated because, as Dr. Brodsky's assistant informs him, "You're getting better...You're becoming healthy, that's all." Perhaps the ultimate image of repression, of Alex becoming healthy, is his licking the sole of the oppressor's black shoe while down on the floor. The Minister of Interior's clinching closing words, "The point is that it works!" sum up the fourth station. Alex's interior has been rewired. Physically he is a free man, but not free from repression. As the clergyman points out, he no longer has a free will.

5) Death in Life:

Having graduated from the university, and holding a wrapped package that he has ostensibly become, Alex returns to his old world crippled for life. What he calls "completely reformed" is, in fact, completely repressed. In his new condition, Alex is easy prey to his former victims, who waste no time in getting even. The first are his parents, who no longer have room for him in his former home. Then, when rescued from "old age having a go at youth" by two of his former droogs, Alex is informed by Georgie that he and Dim "are now of job age." As policemen, they have become agents of aggression. Their day of revenge has finally come.

Like Dorothy in The Wizard of Oz, Alex returns "home." "Home, home home. It was home I was wanting." Unlike Dorothy, however, he returns "not realizing, in the state I was in, where I was and had been before." The writer Alexander, whose "home" Alex returns to, is a picture of what Alex could have become as a healthy (repressed) member of society. In the womb-like bathtub, he returns to his former self, if only by song, reminding the writer what he had perpetrated while singing the very same song. Despite his liberal views, the writer is hardly liberated from unleashing some of his own ultra-violence. Unable to do the killing himself, he takes revenge by driving Alex to "snuff it" with Beethoven's Ninth Symphony just as he had crippled him with "Singing in the Rain." The speakers from which the music blares in the room below Alex's, placed on the green felt of the pool table, evoke an image of two tombstones on a green cemetery lawn.

6) Resurrection:

Between stations five and six the screen goes dark for a brief moment, which leaves us thinking that Alex is dead. And in a way, he is. He has died and resurrected. "I came back to life after a long, black, black gap of what might have been a million years." Alex's parents, whom he calls Pee and Em, are by his bedside, welcoming him back home. But Alex has undergone too much to go back. Whereas Dorothy told Em about her dream, Alex tells the woman psychiatrist (rather than his parents) about a recurring "nasty dream" he had when he was "all smashed up, you know, and half awake and unconscious like."

Apart from his re-erection, Alex's resurrection is his becoming conscious of what he experienced under repression, what he endured. "All the doctors were playing around with me gulliver. You know, like inside of me brain." In asking the psychiatrist about his recurring dream, "Do you think it means anything?" Alex is inquiring about his unconscious, trying to make it conscious. As the psychiatrist assures him, "It's all the part of the recovery process." Alex is recovered enough to enjoy again Beethoven's Ninth Symphony, and from much larger speakers than the ones that drove him to his symbolic death.

Like the huge speakers that amplify the music, the six-station pattern amplifies the movie to a "psychological myth." What Kubrick tried to do in 2001, "to create a visual experience, one that bypasses verbalized pigeonholing and directly penetrates the subconscious with an emotional and philosophic content... just as music does,"2 can be said about Clockwork Orange, a compellingly visual movie in which music and the underlying pattern of transformation play a vital part in the cinematic experience. Commenting on the movie, Kubrick emphasized that "the important point here is that the film communicates on a subconscious level, and the audience responds to the basic shape of the story on a subconscious level, as it responds to a dream." 3In other words, just as Alex is subjected to the Ludovico treatment, primarily through cinematic images and music, in Clockwork Orange, O my brothers, Kubrick subjects us to a similar treatment by projecting on the screen the pattern of transformation in our gullivers.

References

- Stanley Kubrick, "Interview," by Joseph Gelmis, from "The Film Director as Superstar," 1969

- Stanley Kubrick, "Playboy Interview, Playboy #15.9, 1968

- Stanley Kubrick, "Interview New York," Bernard Weinraub, 1973

Gershon Reiter, a former high school teacher of film and music, lives on a kibbutz in Israel. Currently he is seeking a publisher for his first book, Fathers and Sons and the Dragon Between Them. The book addresses the father-son relationship in American movies by re-examining ancient dragon-slaying myths, showing how they apply to movies that deal with fathers and sons. Gershon Reiter, a former high school teacher of film and music, lives on a kibbutz in Israel. Currently he is seeking a publisher for his first book, Fathers and Sons and the Dragon Between Them. The book addresses the father-son relationship in American movies by re-examining ancient dragon-slaying myths, showing how they apply to movies that deal with fathers and sons.

[Photographs from A Clockwork Orange and The Wizard of Oz were downloaded from Wikipedia. These works are copyrighted and unlicensed. They do not fall into one of the blanket fair use categories listed at Wikipedia:Fair use#Images. However, it is believed that the use of this work in this article:

- To illustrate the object in question

- Where no free equivalent is available or could be created that would adequately give the same information

qualifies as fair use under United States copyright law.]

Return to Mythic Passages Menu

Subscribe to the Mythic Passages e-zine

|