|

Rapunzel, Rapunzel, Let Down Your Hair

© Terri Windling

First published at EndicottStudio.com, and used by permission

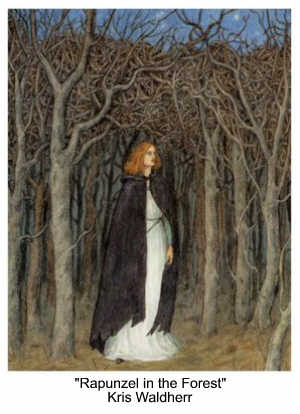

[Images: "Rapunzel in the Forest" and "The Reunion" © Kris Waldherr, www.artandwords.com used by permission]

Maiden-in-a-Tower stories can be found in folk traditions around the world — but "Rapunzel," the best known of these stories, comes from literary sources. The version of "Rapunzel" we know today was published as a German folk tale by the Brothers Grimm in 1857 — but it's now believed that their "Rapunzel" was neither German nor a proper folk tale. Scholars have shown that a number of the storytellers from whom the Brothers Grimm obtained their material were recounting "authored" tales from German, French, and Italian literary sources rather than anonymous folk stories passed orally from teller to teller. The Grimms' "Rapunzel," for example, was derived from a story of the same name published by Friedrich Schultz in 1790 — which was a loose translation of an earlier French story, "Persinette" by Charlotte-Rose de La Force, published in 1698 at the height of the "adult fairy tale" literary movement in Paris. La Force's tale was influenced by an even earlier Italian story, "Petrosinella" by Giambattista Basile, published in 1634 in his story collection Lo Cunto de li Cunti (also known as the Pentamerone). Maiden-in-a-Tower stories can be found in folk traditions around the world — but "Rapunzel," the best known of these stories, comes from literary sources. The version of "Rapunzel" we know today was published as a German folk tale by the Brothers Grimm in 1857 — but it's now believed that their "Rapunzel" was neither German nor a proper folk tale. Scholars have shown that a number of the storytellers from whom the Brothers Grimm obtained their material were recounting "authored" tales from German, French, and Italian literary sources rather than anonymous folk stories passed orally from teller to teller. The Grimms' "Rapunzel," for example, was derived from a story of the same name published by Friedrich Schultz in 1790 — which was a loose translation of an earlier French story, "Persinette" by Charlotte-Rose de La Force, published in 1698 at the height of the "adult fairy tale" literary movement in Paris. La Force's tale was influenced by an even earlier Italian story, "Petrosinella" by Giambattista Basile, published in 1634 in his story collection Lo Cunto de li Cunti (also known as the Pentamerone).

Each writer in this chain used folk motifs drawn from oral tales (associated with peasants and the countryside), reworking them into literary tales (for adult readers who were educated, urban, and upper-class). It is difficult, however, to draw a sharp line between folk tales and literary fairy tales, placing "Rapunzel" in one category or another — for after the Basile, La Force, and Schultz publications, "Rapunzel" slipped into the oral tradition of storytellers throughout the West, where it's now part of our folk culture even though it didn't start there.

Let's go back to the start, however, with Giambattista Basile's "Petrosinella." Basile, born near Naples, drew plots and characters from the folk tales of the region, re-working them into courtly tales for the Italian aristocracy. What follows is a bare-bones summary of his story, without the clever turns of language that make Basile's work so sprightly and distinctive. (I suggest reading Basile's story in full in a good English translation — such as the one provided by Jack Zipes in his book The Great Fairy Tale Tradition.)

Once upon a time, the tale begins, a woman looked out her window at the garden of her neighbor, an ogress, and developed a terrible hunger for the fine parsley growing there. Now, this woman was pregnant, and it was widely believed that denying the cravings of a pregnant woman could cause grave harm to mother and child — so she snuck into her neighbor's garden, not once, but over and over. The ogress laid a trap and caught her. "What do you have to say for yourself, thief?" Once upon a time, the tale begins, a woman looked out her window at the garden of her neighbor, an ogress, and developed a terrible hunger for the fine parsley growing there. Now, this woman was pregnant, and it was widely believed that denying the cravings of a pregnant woman could cause grave harm to mother and child — so she snuck into her neighbor's garden, not once, but over and over. The ogress laid a trap and caught her. "What do you have to say for yourself, thief?"

The woman threw herself on her neighbor's mercy, but the ogress was not appeased. "I will spare your life only if you give me the child you carry, be it boy or girl." The frightened woman agreed and slunk back home, pockets full of parsley.

She soon gave birth to a beautiful baby girl and named her Petrosinella (derived from the word for parsley in the Neapolitan dialect). By the time the child was seven years old, her mother had forgotten all about her promise. But when Petrosinella started school, her path took her by the ogress's house.

Each time that Petrosinella passed, the old ogress called out to her: "Tell your mother to remember the promise she made to me, Petrosinella!" The child did as she was told. Her mother grew more and more frightened, until one day she cried out: "Tell that woman my answer is: 'Take her!'"

When Petrosinella delivered this message, the ogress grabbed her by the hair, carried her deep into the forest, and locked her in a tall stone tower. The tower had no door or stairs, just a small window at the very top, and there the child would sit, straining to catch a small ray of sun. The girl grew up in this lonely place. The ogress was her only company, climbing in and out of the tower on the long, gold braids of Petrosinella's hair.

Years passed, and Petrosinella grew into a beautiful young woman, her golden braids so long they coiled on the ground below. It happened that a prince, who was hunting nearby, became separated from his fellows. He stumbled through the forest, lost, and came upon the tower. The ogress was away and Petrosinella sat in the window sunning her hair. She was the most beautiful young woman the prince had ever seen, and he instantly fell in love. He called up to Petrosinella, and for several days they conversed and sighed and pledged their love. Then Petrosinella proposed a plan to meet when the moon had risen. That night, she gave the old ogress a dose of poppy to make her sleep, then she threw her braids over the windowsill and pulled the young man up. The prince then "made a little meal out of the parsley sauce of love." Years passed, and Petrosinella grew into a beautiful young woman, her golden braids so long they coiled on the ground below. It happened that a prince, who was hunting nearby, became separated from his fellows. He stumbled through the forest, lost, and came upon the tower. The ogress was away and Petrosinella sat in the window sunning her hair. She was the most beautiful young woman the prince had ever seen, and he instantly fell in love. He called up to Petrosinella, and for several days they conversed and sighed and pledged their love. Then Petrosinella proposed a plan to meet when the moon had risen. That night, she gave the old ogress a dose of poppy to make her sleep, then she threw her braids over the windowsill and pulled the young man up. The prince then "made a little meal out of the parsley sauce of love."

More nights of love-making followed until an old gossip got wind of this. She told the ogress what was going on, warning her that her "daughter" might up and fly if she didn't act quickly. The ogress was unperturbed, saying: "She won't be able to get very far without the use of my magic acorns, and I've carefully hidden them in a little spot above the rafters."

Petrosinella had been listening at the window, and she quickly made a plan. She told her lover to bring some rope, then she drugged the ogress to sleep again, stole the three acorns, and used the rope to leave the tower. They hadn't gone very far when the ogress woke and discovered the girl's escape, using her magic to catch up to the fleeing lovers in no time. Petrosinella threw down the first acorn. It turned into a ferocious dog — but the ogress drew bread from her pocket and fed the dog so it let her pass. Petrosinella threw down the second acorn. It turned into a raging lion. The ogress stole the skin from a grazing ass and charged into the lion, which reared back from this monstrous apparition and fled in fright. Petrosinella threw down the third acorn. It turned into a hungry wolf, which quickly gobbled up the ogress before she could use her magic again to save herself.

Now the lovers were safe. They traveled on to the prince's own kingdom, where "with the kind permission of his father, the prince made Petrosinella his wife and proved that, after many trials and tribulations, one hour in a safe harbor can make you forget one hundred years of storm."

Sixty years after Basile's "Petrosinella," the French writer Charlotte-Rose de La Force borrowed elements from it to use in her own Maiden-in-a-Tower story, "Persinette," published in her fairy tale collection Les Contes des Contes in 1697. (This, of course, was a practice much more common in the days before copyright laws; particularly among writers of fairy tales, where the practice continues to this day.) La Force was part of a group of writers (including Madame D'Aulnoy, Madame de Murat, and Charles Perrault) who created a vogue for adult fairy stories in the literary salons of Paris. Like Basile, La Force was writing for an educated, aristocratic audience, creating stories that were meant both to entertain and to comment on issues of contemporary life.

One issue of particular concern to women of the period was the common practice of arranged marriages, particularly among the upper classes. Women had no legal say in these arrangements, often conducted as business transactions between one aristocratic family and another. Daughters were used to cement alliances, to curry favor, and to settle debts. Sex was a husband's legal right, and there was no possibility of divorce. Young girls could find themselves married off to men many years their senior or of vile temper and habits; disobedient daughters could be shut away in convents or locked up in mad-houses. Little wonder, then, that French fairy tales are filled with girls handed over to various wicked creatures by cruel or feckless parents, or locked up in enchanted towers where only true love can save them.

La Force and other writers of the period championed the idea of consensual, companionate marriages ruled by love and civility. (Some also believed that Fate intended certain souls to be together.) The emphasis on love and romance in their stories can seem quaint and saccharine today, but such stories were progressive, even subversive, in the context of the time. La Force herself was an independently-minded woman from a noble family who caused several scandals in her quest to live a life that was self-determined. She fell in love and attempted to marry a young man without parental permission. When his family locked him up to prevent an elopement, she snuck into his room dressed as a bear with a traveling theater troupe! The couple escaped, and married — but the law eventually caught up to them and the marriage was annulled. She then got caught publishing satirical works critical of King Louis XIV. La Force was exiled to a convent for this crime — where she wrote her book of fairy tales and a series of popular historical novels. Eventually released, she spent the rest of her life earning her own living through her writing.

Like all of La Force's fairy tales, "Persinette" is a sensual, sparkling confection with a sly, sharp humor at its center. It's not hard to see why the tale of a girl locked away in a tower would have appealed to her.

Once upon a time, the tale begins, a young couple prepares for the birth of their child, and all is well until the wife conceives a passionate craving for parsley. Her doting husband steals the parsley out of a fairy's enchanted garden. (The gate stands temptingly open, implying the fairy knows very well what will happen — and may, indeed, have magically caused the craving that sets the tale in motion. Fairies are well known, after all, for their penchant for stealing infants.) The second time the husband sneaks into the garden (again he finds the gate open), the fairy catches him and demands his unborn child as payment. The man agrees "after a short deliberation." When his wife gives birth to a beautiful baby girl, she promptly hands the child over to the fairy without a word of protest. Once upon a time, the tale begins, a young couple prepares for the birth of their child, and all is well until the wife conceives a passionate craving for parsley. Her doting husband steals the parsley out of a fairy's enchanted garden. (The gate stands temptingly open, implying the fairy knows very well what will happen — and may, indeed, have magically caused the craving that sets the tale in motion. Fairies are well known, after all, for their penchant for stealing infants.) The second time the husband sneaks into the garden (again he finds the gate open), the fairy catches him and demands his unborn child as payment. The man agrees "after a short deliberation." When his wife gives birth to a beautiful baby girl, she promptly hands the child over to the fairy without a word of protest.

The fairy raises the child tenderly until Persinette (as she's come to be called) reaches the age of puberty. Then, in order to keep the girl safe from harm (the eyes and attention of men), the fairy builds a magnificent silver tower deep in the forest. It contains all that the girl could desire: large and airy rooms elegantly furnished; wardrobes full of sumptuous clothes; delicious meals that are gracefully served by invisible fairy servants; books, paints, and instruments so Persinette need never be bored. What it doesn't have is a door or stairs, so whenever the fairy comes to call she says, "Persinette, let down your hair," and she climbs up through the window.

Years pass, and one day the son of the king is hunting in the forest nearby. He hears the maiden singing and falls in love with her, sight unseen. He finds his way to the tower and spies a shadowy figure far above — but when he calls to her, Persinette takes fright. It's been many years since she's seen a man, and the fairy has told her that some are monsters who can kill with a single look. The prince leaves discouraged, but he cannot forget the sound of that lonely, lovely voice. He makes inquiries in a nearby village and learns that the girl is a fairy's prisoner.

The prince returns, waits, and watches how the fairy goes in and out of the tower. The next day, when the fairy is gone, he stands and calls out in the fairy's voice: "Persinette, let down your hair." Her long gold hair comes tumbling down, he climbs, and steps into the tower. Persinette is frightened once again — but she soon recovers her aplomb as the prince persuades her of his love. He proposes to marry her there and then, and she "consented without hardly knowing what she was doing. Even so," writes La Force archly, "she was able to complete the ceremony."

The prince continues to visit the tower, and before long Persinette grows fat. Innocent, she doesn't know she's pregnant — but the fairy certainly does. Furious, the fairy takes up a knife and cuts off Persinette's long braids, then she sends her off in a flash of fairy magic to a remote place. The fairy hangs the braids from the tower window and waits for the prince to come. He clambers over the windowsill and is shocked to find his lover gone. The fairy angrily informs the prince he'll never see Persinette again, and she flings him from the tower. He lands in briar thorns, which blind him. The prince continues to visit the tower, and before long Persinette grows fat. Innocent, she doesn't know she's pregnant — but the fairy certainly does. Furious, the fairy takes up a knife and cuts off Persinette's long braids, then she sends her off in a flash of fairy magic to a remote place. The fairy hangs the braids from the tower window and waits for the prince to come. He clambers over the windowsill and is shocked to find his lover gone. The fairy angrily informs the prince he'll never see Persinette again, and she flings him from the tower. He lands in briar thorns, which blind him.

For several years the prince wanders the world, living on charity, till at last he reaches a remote place where he hears his wife singing. Persinette now has twin children, who instantly recognize the blind man as their father. Persinette cries with joy, and her tears magically restore his sight.

But wait! The fairy is still angry, and not yet prepared to leave them be. The food in the larder turns into stones, the well fills up with venomous snakes, the birds in the sky above turn into dragons breathing fire. The little family huddles together, preparing to die of the fairy's wrath — but the lovers are happy, nonetheless, to have found each other at last. At this, the fairy's heart finally melts. She sees that their love is strong and true. She forgives them, blesses their marriage, and transports them to the king's castle, where the king and queen welcome their son and his family with open arms.

Friedrich Schultz's "Rapunzel," published in Germany one hundred years later, faithfully follows La Force's plot while toning down the flowery language common to fairy tales of the earlier period. The only marked change Schultz makes to the story is that the fairy is portrayed with greater sympathy. Confronting Rapunzel's pregnancy, she's more Disappointed Mother than Vengeful Fury; and she doesn't throw the prince from the tower — he leaps himself, in a fit of despair. Overall, Schultz merely re-tells La Force's tale rather than spinning it into something new.

The oral version of "Rapunzel" collected by the Grimms half a century after the Schultz publication follows the Schultz and La Force plot, and is clearly derived from one or both. But the Grimms made several changes before they published their "Rapunzel" in 1857. Once again, the story begins with the overwhelming cravings of a pregnant woman. She craves rapunzel (a form of lettuce), which grows in the garden of a sorceress. (The Grimms often edited fairies out of their stories, for they considered the creatures to be too French. It was not until later English versions that the sorceress became a witch.) When she reaches the age of puberty, the girl is locked up in a tower by the woman she now calls Mother Gothel (a generic name for a godmother). The tower has no door or stairs, and the only way to enter it is to stand and deliver the famous line: "Rapunzel, Rapunzel, let down your hair."

The prince hears the maiden singing, finds the tower, and cannot get into it. He rides home again, but returns each day, compelled by the beauty of her song. When he sees the sorceress come and go, he learns at last how the tower is entered. "If that's the ladder one needs," he says, "I'm also going to try my luck." The prince hears the maiden singing, finds the tower, and cannot get into it. He rides home again, but returns each day, compelled by the beauty of her song. When he sees the sorceress come and go, he learns at last how the tower is entered. "If that's the ladder one needs," he says, "I'm also going to try my luck."

He enters the tower, calms the frightened princess, and declares his undying love for her. He offers her his hand in marriage, and Rapunzel chastely accepts. Thereafter, he visits Rapunzel each evening when Mother Gothel is safely away. Each time he comes, he brings a skein of silk so she can weave a ladder to escape.

One day, as the sorceress climbs her hair, Rapunzel absentmindedly asks her why is she so much heavier than the prince? Mother Gothel guesses all and flies into a terrible rage. She cuts off Rapunzel's hair, banishes her to a distant wilderness, and waits for the prince to come that night, where she confronts him with his crimes. He leaps from the tower, is blinded by the thorns, and then wanders the world seeking Rapunzel — who's now referred to as his "wife." They re-unite, his sight is restored, and he learns he has two children. He takes them home to his father's court, and no further mention is made of Mother Gothel.

Although the Grimms originally expected their folk tale collection to be of interest primarily to scholars, they soon realized they had a large and lucrative readership among children and their parents. With each subsequent edition, they edited the stories further to make them more appropriate for young readers, deleting sexual references, and making heroines more virtuously moral. Thus, in their version of "Rapunzel," they glide right over the conception of the twins, and over the fact of her pregnancy, until the children appear, without explanation, at the story's end. Because of the world-wide popularity of the Grimms' now-classic volume of tales, this children's version of "Rapunzel" is the one best known today.

As fairy tales continued to be pushed to the children's shelves in the 20th century, the Grimms' version of "Rapunzel" was re-told over and over in countless picture books — sometimes edited further to delete the existence of those awkward twins altogether. In the public mind, Rapunzel's tale was one intended for very young readers — with few realizing that at its root this is a story about puberty, sexual desire, and the evils of locking young women away from life and self-determination. In the children's version, Rapunzel is just another passive princess waiting for her prince to come. In the older tales we glimpse a different story: about a girl whose life is utterly controlled by greedy, selfish, capricious adults ... until she disobeys, chooses her own fate, and bursts from captivity into adult life, symbolized by the birth of her own children in a distant land.

In the latter decades of the 20th century, Rapunzel's story began to change again as fairy tales began re-appearing in poetry and fiction for adult readers. This new literary fairy tale movement was pioneered by feminist writers such as Anne Sexton, and Angela Carter, and by genre writers such as Robin McKinley, Jane Yolen, and Tanith Lee.

Donna Jo Napoli's Zel, for example, is one of the very best renditions of the "Rapunzel" fairy tale. The novel is set in Switzerland in the middle of the 16th century, told from three different points of view: Zel (Rapunzel), her mother (combining the role of mother and witch), and Konrad (the son of a count). This is a dark, psychologically complex story, delving deep into each character's psyche: a mother unhinged by the possessive nature of her love, a daughter scarred by imprisonment, a young man obsessively in love with a girl he barely knows. It's a taut, beautifully written novel and highly recommended. Donna Jo Napoli's Zel, for example, is one of the very best renditions of the "Rapunzel" fairy tale. The novel is set in Switzerland in the middle of the 16th century, told from three different points of view: Zel (Rapunzel), her mother (combining the role of mother and witch), and Konrad (the son of a count). This is a dark, psychologically complex story, delving deep into each character's psyche: a mother unhinged by the possessive nature of her love, a daughter scarred by imprisonment, a young man obsessively in love with a girl he barely knows. It's a taut, beautifully written novel and highly recommended.

In her story "Touk's House," Robin McKinley uses elements from "Rapunzel", but re-works the plot extensively. Here, a woodcutter's newborn daughter is the price he pays for stealing healing herbs. The witch is a sympathetic figure, raising the girl like her own daughter, and teaching her the herb lore with which she'll eventually win the hand of a prince. But the girl doesn't want the prince in the end, choosing the witch's sweet son instead. Gregory Frost's "The Root of the Matter," by contrast, is a dark and very adult tale exploring the sexual tensions inherent in the story, and its consequences. Here Mother Gothel is a woman deeply damaged by a history of abuse, and she damages the child she has forcibly adopted in turn. The story is told from three points of view: Mother Gothel, Rapunzel, and the Prince — the latter two undergoing true transformation by the story's end.

Abuse also factors into Esther Friesner's darkly comic story "Big Hair," about a girl on the beauty pageant circuit, her life controlled by her witch-like mother. The "prince" is a newspaper reporter who sneaks past the watchful mother's guard, and here, too, we see how abuse is cycled and a maiden can become a witch. Lisa Russ Spaar's story "Rapunzel's Exile" is brief but packs an emotional wallop. Spaar imagines Rapunzel's journey as her Godmother leads her into the forest, and her dawning horror as she realizes that the tower will be her fate. For twelve years her Godmother raised her kindly — but now, with the onset of menstruation (her skirts still bloody, her body still seeping), her Godmother has turned into a different creature, pushing her into the tower at knife point, and walling up the door with stones.

The heroine of Emma Donoghue's "The Tale of the Hair" has chosen to live in a crooked stone tower. She's blind, and she has come to fear the sounds of the forest around her. "Block up the windows and doors," she tells the wise-woman who is her guardian and companion. One night a prince hears her singing, climbs up the tower, and introduces her to love. But soon she learns that the unseen prince is not quite what she thought .... Elizabeth Lynn's delightful "The Princess in the Tower" is set in an obscure and remote village somewhere in the hills of Europe: a place with fabulous, fattening food, and where zaftig women are prized. Poor Margeritina is so slim that everyone thinks she's ill and hideous. She stays in the family house in shame, trying to no avail to put on weight — until a young man stumbles into the village, hears her singing from her high window, falls in love, and whisks her away to marry him and start a restaurant. The charm of the story lies in Lynn's telling, and in the sumptuous food descriptions. Anne Bishop's "Rapunzel" is a moving tale that is broken into three distinct parts: the mother's story, the witch's story, and finally Rapunzel's story. The first two parts are contrasting narratives of jealousy and greed; the third follows Rapunzel to the wilderness, where she finds new life beyond the tower. The heroine of Emma Donoghue's "The Tale of the Hair" has chosen to live in a crooked stone tower. She's blind, and she has come to fear the sounds of the forest around her. "Block up the windows and doors," she tells the wise-woman who is her guardian and companion. One night a prince hears her singing, climbs up the tower, and introduces her to love. But soon she learns that the unseen prince is not quite what she thought .... Elizabeth Lynn's delightful "The Princess in the Tower" is set in an obscure and remote village somewhere in the hills of Europe: a place with fabulous, fattening food, and where zaftig women are prized. Poor Margeritina is so slim that everyone thinks she's ill and hideous. She stays in the family house in shame, trying to no avail to put on weight — until a young man stumbles into the village, hears her singing from her high window, falls in love, and whisks her away to marry him and start a restaurant. The charm of the story lies in Lynn's telling, and in the sumptuous food descriptions. Anne Bishop's "Rapunzel" is a moving tale that is broken into three distinct parts: the mother's story, the witch's story, and finally Rapunzel's story. The first two parts are contrasting narratives of jealousy and greed; the third follows Rapunzel to the wilderness, where she finds new life beyond the tower.

Contemporary poets have also looked at the tale through the eyes of its different characters, finding in the story's themes issues relevant to our lives today.

Carolyn Williams-Noren gives voice to the least sympathetic character in the story in "Rapunzel's Mother":

I can't explain why I wanted that simple

thing so much: dark green rampion leaves, the curled

coverlets of them stacked together on the sideboard,

the rainy steam of them cooking, the hot full softness

and the bittersweet bite in my throat, mouthful

after mouthful. It was as if there was no other way to keep alive.

Nicole Cooley reflects on a troubled mother-daughter relationship in her poem "Rampion":

Tiny blue flowers furred with dirt are all the woman desires

in the story my mother reads over and over. Once upon a time

a woman longed for a child, but see how one desire easily

replaces the next, see her husband climbing the tall garden wall

with a handful of rampion, flowering scab she's traded for a child.

Look, my mother says, see

how the mother disappears

as rampion's metallic root splits the tongue like a knife

and the daughter spends the rest of the story alone.

Dorothy Hewett's chilling poem "Grave Fairy Tale" looks at the witch, through Rapunzel's eyes:

She was there when I woke, blocking the light,

or in the night, humming, trying on my clothes.

I grew accustomed to her; she was as much a part of me

as my own self; sometimes I thought, "She is myself!"

a posturing blackness, savage as a cuckoo ....

Both Anne Sexton and Olga Broumas cast the relationship between Rapunzel and Mother Gothel as a sexual one. In Sexton's "Rapunzel," she writes of a lesbian affair between a student and her mentor, which the younger woman ends when a "prince" offers her a more socially acceptable life:

As for Mother Gothel,

her heart shrank to the size of a pin,

never again to say: Hold me, my young dear,

hold me,

and only as she dreamt of the yellow hair

did moonlight sift into her mouth.

Broumas, by contrast, celebrates such relationships in her answering poem "Rapunzel," writing in the voice of a younger woman who has no such temptation to stray:

Climb

through my hair, climb in

to me, love / hovers here like a mother's wish.

... How many women

have yearned

for our lush perennial, found

themselves pregnant, and had

to subdue their heat, drown out their appetite

with pickles and hard weeds.

David Trinidad's "Rapunzel" grows desperate in her isolation:

Like hair, the days and nights are growing longer and longer.

.... And each evening the crone comes. Her crackled fingers appear

pinching the key ....

If only once she'd say: "Here,

take this pair of scissors and cut your hair before it twists

into spaces between the bricks like vines." I'd slit my wrists.

In Liz Lochhead's "Three Twists," on the other hand, Rapunzel discovers there are worse things than solitude — like a prince who hasn't got a clue about what she really needs:

... and just when our maiden had got

good and used to her isolation

stopped daily expecting to be rescued,

had come almost to love her tower,

along comes This Prince

with absolutely all the wrong answers

The prince in Sara Henderson Hay's "Rapunzel is all too skilled at the language of love:

Oh God, let me forget the things he said.

Let me not lie another night awake

Repeating all the promises he made ....

I knew I was not the first to twist

Her heartstrings to a rope for him to climb.

I might have known I would not be the last.

Alice Friman's poem "Rapunzel" displays a bit more sympathy for the prince:

If she was unwise about such things

that girls are taught of men

with chocolate kisses / who offer lifts to lessons

who stand too close in subways

playing with their change

then what was he?

Caught in that small room,

the braid

coiling the floorboards like a snake,

and she all Rubens — ripe and curious.

Oh, the tower — singing on the wheezy couch.

Forbidden fruits in platters of her flesh

and he with scars to touch along his side

and many wondrous things to name.

Bruce Bennett's "The Skeptical Prince" wants proof that there's really a maiden in that tower:

The town has grown accustomed to the sight:

he drinks by day, then hangs around at night,

purveying sad and antiquated lore,

insisting he will act once he is sure

In "Rapunzel" by Arlene Ang, we never quite know what it is the prince encounters when he climbs into the tower. Is it the witch with Rapunzel's braids, or Rapunzel herself who is terrifying?:

The twelfth prince climbed the tower

on golden tresses he knew were here.

When he penetrated her window,

she turned away to light the fire.

His eyes blinded by hair that mirrored

the leap of flames she stoked,

the prince failed to see the woodpile

of chewed bones at the corner of the hearth.

Essex Hemphill's "Song of Rapunzel" reminds us that sometimes men need rescuing too:

His hair

almost touches

his shoulders.

He dreams

of long braids,

ladders,

vines of hair.

He stands

like Rapunzel,

waiting on his balcony

to be rescued

from the fire-breathing

dragons of loneliness.

Rosemary Dun's "Rapunzel" rescues herself from prince and tower alike:

... I cut off the long hank of my

just-for-him hair with golden shears,

so that no more would he climb,

prick my finger,

nor ravish me awake.

Instead, my howls which once

had filled my madwoman's attic

with despair.

announce the birth of my

daughter.

We hold hands and jump.

Lisa Russ Spaar's "Rapunzel Shorn" is a young woman tasting sweet freedom at last:

I'm redeemed, head light

as seed mote, as a fasting

girl's among these thorns, lips

and fingers bloody with fruit.

Years I dreamed of this:

the green, laughing arms

of old trees extended over me,

my shadow lost among theirs.

Gwen Strauss' "The Prince" is an old man now, living with his beloved wife and looking back over the events of his life: Gwen Strauss' "The Prince" is an old man now, living with his beloved wife and looking back over the events of his life:

For a long time I was blind,

even before the thorns tattered my eyes.

I was bored, handsome, a Prince.

The thrill was in what I could get away with.

... All my childhood I heard about love

but I thought only witches could grow it

in gardens behind walls too high to climb.

Rapunzel's story has become part of our folk tradition because its themes are universal and timeless. We've all hungered for things with too high a price; we've all felt imprisoned by another's demands; we've all been carried away by love, only to end up blinded and broken; we all hope for grace at the end of our suffering, and a happy ending. The story has additional resonance, of course, for those of us who were given up by one or both of our birth parents, as it does for those raised by parents who are over-protective or over-controlling. In the end, the story tells us, we have to leave the tower one way or another, weave a ladder or leap into the thorns. We can't stay in childhood forever. The adult world, with all its terrors and wonders, waits for us just beyond the forest.

Further Reading:

Short Stories:

- "Rapunzel" by Anne Bishop (from Black Swan, White Raven

, Avon, 1997) , Avon, 1997)

- "The Tale of the Hair" by Emma Donoghue (from Kissing the Witch

, HarperCollins, 1997) , HarperCollins, 1997)

- "Big Hair" by Esther Friesner (from Black Heart, Ivory Bones

, Avon, 2000) , Avon, 2000)

- "The Root of the Matter" by Gregory Frost (from Snow White, Blood Red (Avonova Book)

, Avon, 1995) , Avon, 1995)

- "The Golden Rope" by Tanith Lee, from Red as Blood or Tales From the Sisters Grimmer

(DAW, 1983) (DAW, 1983)

- "Rapunzel" by Tanith Lee, from Black Heart, Ivory Bones

(Avon, 2000) (Avon, 2000)

- "Rapunzel Dreams of Knives" by Beth Adele Long, from Strange Horizons (October 17, 2005 issue) (read it here online)

- "The Princess in the Tower" by Elizabeth Lynn (from Snow White, Blood Red (Avonova Book)

, Avon, 1995) , Avon, 1995)

- "Touk's House" by Robin McKinley (from A Knot in the Grain and Other Stories

, Greenwillow, 1994) , Greenwillow, 1994)

- "The Girl in the Attic" by Lois Metzger, from Swan Sister: Fairy Tales Retold

(Simon & Schuster, 2003) (Simon & Schuster, 2003)

- "Melisande" by E. Nesbit, from Nine Unlikely Tales (Fisher Unwin, 1901; read it online here)

- "Thy Golden Stair" by Richard Parks, from Twice upon a Time

(DAW 1999) (DAW 1999)

- "Rapunzel's Exile" by Lisa Russ Spaar (from Ploughshares, Vol. 22, No. 4, and The Year's Best Fantasy and Horror: Tenth Annual Collection

, St. Martin's Press,1997) , St. Martin's Press,1997)

- "Maiden in a Tower" by Wallace Earl Stegner, from The City of the Living, and Other Stories (Short Story Index Reprint Series)

(Houghton Mifflin, 1956) (Houghton Mifflin, 1956)

Poetry:

- The Poets' Grimm: 20th Century Poems from Grimm Fairy Tales

edited by Jeanne Marie Beaumont and Claudia Carlson, containing fourteen Rapunzel poems (Story Line Press, 2003) edited by Jeanne Marie Beaumont and Claudia Carlson, containing fourteen Rapunzel poems (Story Line Press, 2003)

- Rapunzel, Rapunzel: Poems by Janet Charman

by Janet Charman, containing a cycle of Rapunzel poems (Auckland University Press, 1999) by Janet Charman, containing a cycle of Rapunzel poems (Auckland University Press, 1999)

- "Rapunzel" by Faye Kicknosway, from American Poetry Since 1970: Up Late

(Four Walls, Eight Windows, 1989) (Four Walls, Eight Windows, 1989)

- Disenchantments: An Anthology of Modern Fairy Tale Poetry

, edited by Wolfgang Mieder, containing seven Rapunzel poems (University Press of New England, 1985) , edited by Wolfgang Mieder, containing seven Rapunzel poems (University Press of New England, 1985)

- "Rapunzel" by William Morris, from The Defence Of Guenevere And Other Poems

(Ellis & White, 1858) (Ellis & White, 1858)

- Rapunzel's Hair by Judy A. Rypma, chapbook (All Nations Press, 2005)

- Glass Town: Poems

by Lisa Russ Spaar, containing a cycle of Rapunzel poems (Red Hen Press, 1999) by Lisa Russ Spaar, containing a cycle of Rapunzel poems (Red Hen Press, 1999)

- "The Golden Stair" by Jane Yolen, from The Faery Flag: Stories and Poems of Fantasy and the Supernatural

(Orchard, 1989) (Orchard, 1989)

Terri Windling, is a writer, folklorist, and consulting editor for Tor Books. She is best known for her editorial work in the field of fantasy literature, where she has long been a passionate advocate of mythic fiction. She has published over forty books, including The Wood Wife (a mythic novel set in contemporary Tucson, Arizona), The Winter Child (a mythic novel set in contemporary Tucson, Arizona), The Winter Child (a picture book with artist Wendy Froud), the six-volume Snow White, Blood Red series (literary fairy tales for adult readers) and The Armless Maiden (literary fairy tales addressing the subject of child abuse) — as well as short stories, children's fiction, and the annual The Year's Best Fantasy & Horror (a picture book with artist Wendy Froud), the six-volume Snow White, Blood Red series (literary fairy tales for adult readers) and The Armless Maiden (literary fairy tales addressing the subject of child abuse) — as well as short stories, children's fiction, and the annual The Year's Best Fantasy & Horror volumes (with horror editor Ellen Datlow). Her essays on myth, fairy tales, and art have appeared in Realms of Fantasy magazine, and in books including Mirror, Mirror on the Wall: Women Writers Explore Their Favorite Fairy Tales volumes (with horror editor Ellen Datlow). Her essays on myth, fairy tales, and art have appeared in Realms of Fantasy magazine, and in books including Mirror, Mirror on the Wall: Women Writers Explore Their Favorite Fairy Tales (Expanded Edition), and Meditations on Middle-Earth, and Fées. Windling has won six World Fantasy Awards, and the 1997 Mythopoeic Award for Novel of the Year. Also an accomplished artist, Windling creates "folkloric" paintings inspired by myth, fairy tales, and women's history. Her art has been exhibited in galleries and museums in the U.S. and abroad. In 1987, Windling created the Endicott Studio, and in 2001 she co-created Endicott West (an arts retreat in Arizona) with Ellen Kushner and Delia Sherman. She is a founding member of the Interstitial Arts Foundation.. (Expanded Edition), and Meditations on Middle-Earth, and Fées. Windling has won six World Fantasy Awards, and the 1997 Mythopoeic Award for Novel of the Year. Also an accomplished artist, Windling creates "folkloric" paintings inspired by myth, fairy tales, and women's history. Her art has been exhibited in galleries and museums in the U.S. and abroad. In 1987, Windling created the Endicott Studio, and in 2001 she co-created Endicott West (an arts retreat in Arizona) with Ellen Kushner and Delia Sherman. She is a founding member of the Interstitial Arts Foundation..

Return to Mythic Passages Menu

Subscribe to the Mythic Passages e-zine

|