|

The Matrix:

The Matrix:

Seeing is Believing

by Gershon Reiter

Unfortunately, no one can be told what the Matrix is. You have to see it for yourself.

Morpheus to Neo

The Matrix

In their 1999 movie, The Matrix, the Wachowski brothers seem to envision a dark version of President Lincoln's closing words to his 1863 "Gettysburg Address": "... that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom, and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth." Contrary to Lincoln's bright vision, in the brave new world of The Matrix the "new birth of freedom" has all but perished from the earth. Now the government is of the Matrix, by the Matrix, and for the Matrix.

Unlike the enslaved Afro-Americans in Lincoln's time, who experienced the hardships of slavery each and every day, in The Matrix most of mankind doesn't even know, doesn't see, that it's enslaved by and for the Matrix. As irony would have it, now it is the freed black Morpheus (the name of the god of dreams in Greek mythology) who informs the enslaved white Neo that "the world that has been pulled over your eyes to blind you from the truth ... that you are a slave." In the world of the Matrix, slavery is of the mind. Most humans are under the spell of the Matrix, believing that what they see is real when in fact it's a simulation. But like Morpheus, there are some people who are not blind to the digital simulation of reality known as the Matrix. These rebels, as they are called, may not be completely free from the Matrix, but they see their situation as it is. They are not fooled. They are living testimony to what Lincoln, known as the Great Emancipator, had stated on another occasion, "You can fool some of the people all of the time, and all of the people some of the time, but you cannot fool all of the people all of the time."

What Lincoln stated in words, the Wachowski brothers convey through the modern medium of film. What Lincoln calls fooled, the Wachowskis call blinded. In their "intellectual action movie"1 some of the people who are not fooled, who are not blinded, are looking for the One who can free mankind from the Matrix. As Morpheus, their leader, informs Neo, whom he believes is the One, the one who will usher the new eon of freedom, "The Matrix is a computer-generated dream world built to keep us under control in order to change a human being into this" (he holds up a battery).

Intended or not, the matrix in the movie that Larry Wachowski claimed "is about the birth and evolution of consciousness"2 is identical to the matrix that the Jungian psychoanalyst Erich Neumann refers to in his book, The Origins and History of Consciousness. Neumann and the Wachowskis view (see) the matrix the same way; only their metaphors are different. Where in Neumann's book the ego is in the grip of the uroboros, the primal dragon that feeds on its own tail, in The Matrix man is an embryo connected to a computer that feeds it like a pregnant mother, while sapping its electrical energy to keep itself going, giving one kind of life while taking another. As implied by the word matrix, which comes from the Latin word for "womb," the Matrix is the devouring mother, the maternal matrix that keeps man enslaved. Both the Wachowskis and Neumann maintain that only when man disengages from the maternal Matrix can he start seeing things as they truly are. Intended or not, the matrix in the movie that Larry Wachowski claimed "is about the birth and evolution of consciousness"2 is identical to the matrix that the Jungian psychoanalyst Erich Neumann refers to in his book, The Origins and History of Consciousness. Neumann and the Wachowskis view (see) the matrix the same way; only their metaphors are different. Where in Neumann's book the ego is in the grip of the uroboros, the primal dragon that feeds on its own tail, in The Matrix man is an embryo connected to a computer that feeds it like a pregnant mother, while sapping its electrical energy to keep itself going, giving one kind of life while taking another. As implied by the word matrix, which comes from the Latin word for "womb," the Matrix is the devouring mother, the maternal matrix that keeps man enslaved. Both the Wachowskis and Neumann maintain that only when man disengages from the maternal Matrix can he start seeing things as they truly are.

What Neo, the movie's hero, undergoes is identical to Neumann's awakening ego. In both cases it "is thrust out from the maternal matrix, and it finds itself by distinguishing itself from the matrix."3 By the same token, what Morpheus tells Neo before taking the red pill ("After this there is no turning back.") is not unlike Neumann's rendering of what happens to the ego when it disengages from the uroboros.

This means the end of that beatific uroboric state of autarchy, perfection, and absolute self-sufficiency so long as the ego was swimming in the belly of the uroboros, a mere ego germ, it shared in that paradisal perfection. This autarchy holds absolute sway in the womb, where unconscious existence is combined with absence of suffering. Everything is supplied of its own accord; there is no need of the slightest exertion, not envy, an instinctive reaction, let alone a regulating ego consciousness. One's own being and the surrounding world — in this case, the mother's body — exists in a participation mystique, never more to be attained in any environmental relationship.4

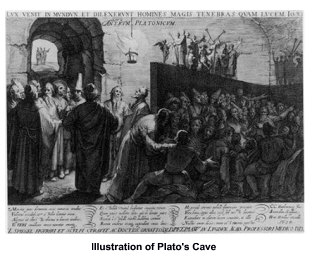

The two choices presented to Neo, to live blindly in the "beatific uroboric state of autarchy," to subsist in the matrix; or to see "how deep the rabbit hole goes," to enter what Morpheus calls "the real world," is something man has been tackling throughout his recorded history. The most famous case is probably Plato's allegory of the cave, which, however inadvertently, is itself an early metaphor for cinema. It, too, is about seeing reality as it is, beyond the shadows of reality reflected on the wall. In fact, all three points of view — Plato's, Neumann's and the Wachowskis' — are about man's mental slavery to simulated reality, where, in Plato's words, "the truth would be literally nothing but the shadows of the images" and "the prison-house is the world of sight."5 Like Plato's allegory, The Matrix is about seeing with a free mind, seeing without the defensive filters that we accumulate from the day we are born, filters that keep most of us sane but neurotic — a minimum-security prison perhaps, but a prison nevertheless. It's what Morpheus calls "a prison you cannot smell or taste or touch; a prison of your mind." It's a prison you can sometime feel but cannot see. The two choices presented to Neo, to live blindly in the "beatific uroboric state of autarchy," to subsist in the matrix; or to see "how deep the rabbit hole goes," to enter what Morpheus calls "the real world," is something man has been tackling throughout his recorded history. The most famous case is probably Plato's allegory of the cave, which, however inadvertently, is itself an early metaphor for cinema. It, too, is about seeing reality as it is, beyond the shadows of reality reflected on the wall. In fact, all three points of view — Plato's, Neumann's and the Wachowskis' — are about man's mental slavery to simulated reality, where, in Plato's words, "the truth would be literally nothing but the shadows of the images" and "the prison-house is the world of sight."5 Like Plato's allegory, The Matrix is about seeing with a free mind, seeing without the defensive filters that we accumulate from the day we are born, filters that keep most of us sane but neurotic — a minimum-security prison perhaps, but a prison nevertheless. It's what Morpheus calls "a prison you cannot smell or taste or touch; a prison of your mind." It's a prison you can sometime feel but cannot see.

Just as in Morpheus' words, "The Matrix is everywhere," The Matrix is different things to different people. There are many ways to see this dream-movie about reality. Beyond its spectacular visual exterior, the movie can be read as a modern myth of slaying the dragon. Much as the Greeks (and other peoples) had stories about the archetypal beast that the mythic hero must slay, so is the Matrix of the movie a mythological beast of immense (but not insurmountable) power, which the hero has to confront and destroy. Like many mythic heroes of the past, the hero of The Matrix is dealing with the devouring mother, the maternal monster that keeps its offspring captive for its own insatiable needs, keeping them dependent and unconscious — unconscious of their dependence. It tricks its victims into believing that what they see is real. It keeps them in a state of blind bliss, a bliss of ignorance, the kind of blissful ignorance that Cypher, who betrays his fellow rebels to the Matrix, wants to return (regress) to.

Where Cypher wants to return to the womb, to the Matrix, Neo wants out. Once he is freed from the shackles of the Matrix and starts to see, he undertakes a journey of self-discovery — what Morpheus calls "free your mind," and what the sign above the door in the Oracle's kitchen reads, "Know Thyself." In both instances it is about knowing and becoming who you truly are, the full person you are destined to be. Neo's quest is to find the answer to the question that has haunted mankind since the dawn of consciousness: What is the Matrix? As Trinity tells Neo in their first meeting, "It's the question that drives us mad"; or as Morpheus puts it in his first face to face meeting with Neo, it is "a splinter in your mind, driving you mad."

Ultimately, it doesn't really matter what the Matrix is. Like God, or our idea of God, it is beyond our comprehension. We can only see its image represented on the screen. And just as the Matrix is infinitely complex, The Matrix is a complex movie that both baffles and intrigues. It leaves us wanting to see more. Like cinema itself, this movie, loaded with many self-reflexive images and references to seeing, is about seeing. Even with its considerable wordiness, it's the seeing that makes The Matrix an incredibly visual experience.

That The Matrix is about seeing is underscored by the Wachowski brothers' two appearances in the movie. Their first "appearance," however veiled, comes in the very opening of the movie, in the Warner Brothers logo. Instead of the usual golden logo set against an azure white-clouded sky, the logo that opens The Matrix is dark green, set against a black sky with the same white clouds. The dark green, the color of the Matrix, sets the tone for the remainder of the movie. But beyond that, seeing how every detail in the movie is thought out, the odds are that the green WB logo stands for the Wachowski brothers. It's the movie's first sign that there is much more to see than first meets the eye, and a sign of things to come. It's as if the familiar golden logo is a simulation and the Wachowskis' logo is reality. Or one is the placebo blue pill, the other one the red pill.

In the Wachowski brothers' second appearance, the subject of seeing is much more apparent. It takes place in Neo's everyday world, his place of work and enslavement, where he goes by the name of Thomas Anderson. A shot of a soaped window being cleaned by a window cleaner's squeegee, which looks surprisingly like the "window" screen of the Matrix, reveals Neo standing before his superior's desk. He remains standing while the sitting superior reprimands him for not waking up on time, a different kind of waking than the one that appeared on his computer screen the night before. From the inside, from Neo's point of view, we see two window cleaners cleaning two of the office's three plate glass windows (not unlike the three screens that show the Matrix). While his superior warns him about his "problem with authority," Neo is distracted by the sound of the window cleaners' squeegees, by the very act that implies not being distracted by distraction: cleansing the windows of perception.

This cleansing of the windows of perception is anticipated in our initial seeing of Neo, when he answers both the visible "Knock, knock, Neo" on his computer screen and the two (audible) knocks on his apartment door. The talk by the doorway about mescaline brings to mind Aldous Huxley's book, Doors of Perception, where he gives an account of his initial experience with mescaline, which helped him to really see for the first time in his life. As Huxley wrote in the book, "I was seeing what Adam had seen on the morning of his creation — the miracle, moment by moment, of naked existence."6 The book's title, of course, is taken from the well-known line of William Blake's Marriage of Heaven and Hell: "If the doors of perception were cleansed, everything would appear to man as it is: infinite." Perhaps this is what Morpheus means when he tells Neo, "I can show you the door, but you must walk through it." Morpheus reiterates this line several times throughout the movie when he tells Neo that he must "see for yourself."

Assuming, as some claim, that the two window washers (unnamed in the credits) are the Wachowski brothers, the two invite us to "see for ourselves," showing the path to free our minds from our own unrecognized matrix. In "copying" Hitchcock in their cameo appearance as window washers, which was foreshadowed by their reworking the rooftop chase that opened Vertigo, the Wachowski brothers suggest that The Matrix is their Rear Window, a movie in which windows are a metaphor for film. As window washers, as creators of The Matrix, the Wachowskis are our very own Morpheus. For just as Morpheus can show Neo the door (of perception) which he will have to walk through, the brothers may cleanse the windows, but we have to see through them with our own eyes.

Calling attention to "seeing," right after the Wachowskis' "wink" through the windows, Neo receives a call from Morpheus who cautions him, "I don't know if you're ready to see what I want to show you." In and by their movie, the Wachowskis are asking us a similar question: "Are you ready to see what we are showing you?" The way they shot their movie, they seem to dare us to see. This is what makes seeing The Matrix so fascinating and so much fun. In many ways, it's a peak in movie making and movie watching, a culmination of what movies have always been about. Much like what Morpheus "want(s) to show" Neo, "the earliest uses of moving pictures were not to entertain, but to put reality in a new light for the sake of better perceiving it."7 And just as seeing makes Doubting Thomas Anderson (Neo) a believer, it's seeing movies that make them so believable. Seeing is believing.

To drive the point home, the theme of seeing is highlighted throughout the movie. It comes up in such seemingly insignificant details as the title of the book, Simulacra and Simulation, in which Neo hides his illegal discs, and in Morpheus' instruction to Trinity in her escape from the agents of the Matrix, "You have to focus, Trinity." It crops up again when a flash of lightning, a widespread symbol for seeing, strikes just as Neo first sees Morpheus. Or when Morpheus tells Neo in the same meeting, "I imagine that right now you're feeling a bit like Alice tumbling down the rabbit hole. I can see it in your eyes. You have the look of a man who accepts what he sees because he's expecting to wake up." The seeing continues when Morpheus informs Neo, "Unfortunately, no one can be told what the Matrix is. You have to see it for yourself." Of course, it's not for nothing that, upon waking up after he is freed from the Matrix, Neo asks, "Why do my eyes hurt?" "You never used them before," Morpheus enlightens him.

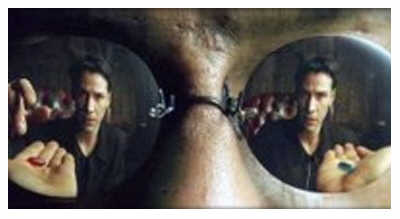

When Neo chooses the red pill (which initiates his seeing), the two pills Morpheus offers him are shown doubly reflected in his dark impenetrable shades, images that underscore Neo's two choices, two lives and two names, not to mention the real and the reflected. One pill shows "how deep the rabbit hole goes." The other one, "the one that mother (Matrix) gives you," in the words of Jefferson Airplane's White Rabbit, "don't do nothing at all." The three shots showing the two pills call attention to the subject of seeing, the medium truly being the message:

- When offered the blue pill, Neo is reflected in each of the two lenses, the right lens showing Morpheus' right hand holding the pill.

- When offered the red pill, which will take him to Wonderland, Neo is reflected in each lens, each one showing a different hand offering a very different pill. During the brief silence that ensues, a flash of lightning comes through the window and a warning thunder roll is heard in the background.

- The third shot is a close up of Morpheus' shades, once again showing the same Neo and two different hands, each one offering a different pill. As Morpheus warns him, "Remember, all I'm offering is the truth, nothing more," Neo is shown reaching for the red pill. Another lightning and thunder punctuate his momentous choice, after which Neo will never be the same, for he is about to be truly awakened. He is about to start seeing. "Follow me," Morpheus beckons him like the white rabbit.

The reflections are repeated in Neo's first venture into the world of the Matrix, to meet with the Oracle. It starts with his reflection in the shiny door knob to her apartment, and continues in the spoon that the Spoon Boy bends, showing Neo that it's all a reflection of his mind. The two, the Oracle and the Spoon Boy, are seers who advance Neo on his quest to see.

Spoon Boy: Do not try and bend the spoon. That's impossible. Instead only try to realize the truth. Spoon Boy: Do not try and bend the spoon. That's impossible. Instead only try to realize the truth.

Neo: What truth?

Spoon Boy: There is no spoon.

Neo: There is no spoon?

Spoon Boy: Then you'll see that it is not the spoon that bends, it is only yourself.

What the Spoon Boy refers to is what the Buddhists call maya, the invisible veil before our eyes, or in Morpheus's words, "the world ... pulled over your eyes." Much as Buddhism sees man's fundamental problem as his attachment to his ego, which is the cause for his inability to see through the illusion of maya, so is the central problem of mankind in the world controlled by the Matrix. Neo's ultimate destiny, like the Buddha's (whose name means the Awakened One), is to awaken to who he really is, free from the rules (control) of the Matrix. Only then can he really see. This is underscored by the tune played in the background when he meets the Oracle, Duke Ellington's I'm Beginning To See The Light. It is another indication that the meeting with the Oracle (and the whole movie) is about seeing. As the Oracle suggests, before he believes he is the One, Neo has to see. Seeing is believing. Seeing sets him free.

- Andy Wachowski to the American Cinematographer

- Larry Wachowski to Richard Corliss, "Popular Metaphysics", Time Magazine (April 19, 1999, VOL. 153, No. 15)

- Erich Neumann, The Origins and History of Consciousness, p. 138

- E. Neumann, p. 33

- Plato, The Republic

- Aldous Huxley, The Doors of Perception, p.17

- Roy Huss and Norman Silverstein, The Film Experience, p. 2

Gershon Reiter, Gershon Reiter, a former high school teacher of film and music, lives on a kibbutz in Israel. His first book, Fathers and Sons and the Dragon Between Them, is to be published sometimes next year by McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers. The book addresses the father-son relationship in American cinema by re-examining ancient dragon-slaying myths, showing how they apply to movies, or to what the book calls filmmyths, that deal with fathers and sons. Gershon Reiter, Gershon Reiter, a former high school teacher of film and music, lives on a kibbutz in Israel. His first book, Fathers and Sons and the Dragon Between Them, is to be published sometimes next year by McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers. The book addresses the father-son relationship in American cinema by re-examining ancient dragon-slaying myths, showing how they apply to movies, or to what the book calls filmmyths, that deal with fathers and sons.

[Photographs from The Matrix were downloaded from Wikipedia. These works are copyrighted and unlicensed. They do not fall into one of the blanket fair use categories listed at Wikipedia:Fair use#Images. However, it is believed that the use of this work in this article:

- To illustrate the object in question

- Where no free equivalent is available or could be created that would adequately give the same information

qualifies as fair use under United States copyright law.]

Return to Mythic Passages Menu

Subscribe to the Mythic Passages e-zine

|