|

The Mythology of Love

from Myths to Live By

© Joseph Campbell, 1972

and used with permission of the Joseph Campbell Foundation

1967

What a wonderful theme! And what a wonderful world of myth one finds in celebration of the universal mystery! The Greeks, it will be recalled, regarded Eros, the god of love, as the eldest of the gods; but also the youngest, born fresh and dewy-eyed in every loving heart. There were, moreover, two orders of love, according to the manners of manifestation of this divinity, in his terrestrial aspect and celestial. And Dante, following the classical lead, saw love suffusing and turning the universe, from the highest seat of the Trinity above to the lowest pits of Hell. What a wonderful theme! And what a wonderful world of myth one finds in celebration of the universal mystery! The Greeks, it will be recalled, regarded Eros, the god of love, as the eldest of the gods; but also the youngest, born fresh and dewy-eyed in every loving heart. There were, moreover, two orders of love, according to the manners of manifestation of this divinity, in his terrestrial aspect and celestial. And Dante, following the classical lead, saw love suffusing and turning the universe, from the highest seat of the Trinity above to the lowest pits of Hell.

One of the most amazing images of love that I know is Persian — a mystical Persian representation of Satan as the most loyal lover of God. You will have heard the old legend of how, when God created the angels, he commanded them to pay worship to no one but himself; but then, creating man, he commanded them to bow in reverence to this most noble of his works, and Lucifer refused — because, we are told, of his pride. However, according to this Moslem reading of his case, it was rather because he loved and adored God so deeply and intensely that he could not bring himself to bow before anything else. And it was for that that he was flung into Hell, condemned to exist there forever, apart from his love.

Now it has been said that of all the pains of Hell, the worst is neither fire nor stench but the deprivation forever of the beatific sight of God. How infinitely painful, then, must the exile of this great lover be, who could not bring himself, even on God's own word, to bow before any other beings!

The Persian poets have asked, "By what power is Satan sustained?" And the answer that they have found is this: "By his memory of the sound of God's voice when he said, 'Be gone!'" What an image of that exquisite spiritual agony which is at once the rapture and the anguish of love!

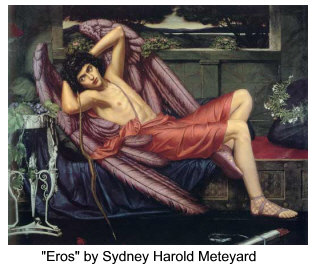

Another lesson from Persia is in the life and words of the great Sufi mystic Hallaj, who in the year 922 was tortured and crucified for having declared that he and his Beloved —namely God—were one. He had compared his love for God with that of the moth for the flame. The moth plays about the lighted lamp till dawn, and returning with battered wings to its friends, tells of the beautiful thing it found; then, desiring to be joined to it entirely, flying into the flame the next night, becomes one with it. Another lesson from Persia is in the life and words of the great Sufi mystic Hallaj, who in the year 922 was tortured and crucified for having declared that he and his Beloved —namely God—were one. He had compared his love for God with that of the moth for the flame. The moth plays about the lighted lamp till dawn, and returning with battered wings to its friends, tells of the beautiful thing it found; then, desiring to be joined to it entirely, flying into the flame the next night, becomes one with it.

Such metaphors speak of a rapture that we all, one way or another, must at one time or another, either intensely or not so intensely, have experienced or at least imagined. But there is another aspect of love, which some may also have experienced, and which is likewise illustrated in a Persian text. This one is from an ancient Zoroastrian legend of the first parents of the human race, where they are pictured as having sprung from the earth in the form of a single reed, so closely joined that they could not have been told apart. However, in time they separated; and again in time they united and there were born to them two children, whom they loved so tenderly and irresistibly that they ate them up. The mother ate one; the father ate the other; and God, to protect the human race, then reduced the force of man's capacity for love by some ninety-nine per cent. Those first parents thereafter had seven more pairs of children, every one of which, however—thank God!—survived.

The old Greek idea of Love as the eldest of the gods is matched in India by that ancient myth from the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad cited above of the Primal Being as a nameless, formless power that at first had no knowledge of itself but then thought, "I," aham, and immediately felt fear that the "me" it now had in mind might be slain. Then, reasoning, "Since I am all there is, what should I fear?" it thought, "I wish there were another!" and, swelling, splitting, became two, a male and a female; out of which primal couple there came into being all the creatures of this earth. And when all had been accomplished, the male looked about, saw the world he had produced, and thought and said, "All this am I!"

In the meaning of this story, that Primal Being antecedent to consciousness—which in the beginning thought, "I!" and felt fear, then desire—is the motivating substance activating each one of us in our unconsciously motivated lives. And the second lesson of the myth is that through our won experiences of the union of love we participate in the creative action of that ground of all being. For, according to the Indian view, our separateness form each other in space and time here on earth—our multitude—is but a secondary, deluding aspect of the truth, which is that in essence we are of one being, one ground; and we know and experience that truth—going out of ourselves, outside the limits of ourselves—in the rapture of love.

The great German philosopher Schopenhauer, in a magnificent essay on "The Foundation of Morality," treats of this transcendental spiritual experience. How is it, he asks, that an individual can so forget himself and his own safety that he will put himself and his life in jeopardy to save another from death or pain — as though that other's life were his own, that other's danger his own? Such a one is then acting, Schopenhauer answers, out of an instinctive recognition of the truth that he and that other in fact are one. He has been moved not from the lesser, secondary knowledge of himself as separate from others, but from an immediate experience of the greater, truer truth, that we are all one in the ground of our being. Schopenhauer's name for this motivation is "compassion," Mitleid, and he identifies it as the one and only inspiration of inherently moral action. It is founded, in his view, in a metaphysically valid insight. For a moment one is selfless, boundless, without ego.  And I have lately had occasion to think frequently of this word of Schopenhauer as I have watched on television newscasts of those heroic helicopter rescues, under fire in Vietnam, of young men wounded in enemy territory: their fellows, forgetful of their own safety, putting their young lives in peril as though the lives to be rescued were their own. There, I would say — if we are looking truly for an example in our day — is an authentic rendition of the labor of Love. And I have lately had occasion to think frequently of this word of Schopenhauer as I have watched on television newscasts of those heroic helicopter rescues, under fire in Vietnam, of young men wounded in enemy territory: their fellows, forgetful of their own safety, putting their young lives in peril as though the lives to be rescued were their own. There, I would say — if we are looking truly for an example in our day — is an authentic rendition of the labor of Love.

In the religious lore of India there is a formulation of five degrees of love through which a worshiper is increased in the service and knowledge of God — which is to say, in the Indian sense, in the realization of his own identity with that Being of all beings who in the beginning said "I" and then realized, "I am all this world!" The first degree of such love is of servant to master: "O Lord, you are the Master; I am the servant. Command, and I shall obey!" This, according to the Indian teaching, is the appropriate spiritual attitude for most worshipers of divinities, no matter where in the world.

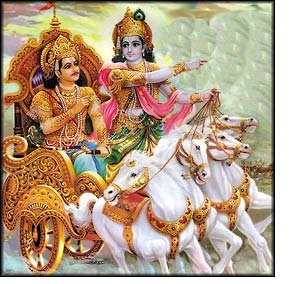

The second order of love, then, is that of friend to friend, which in the Christian tradition is typified in the relationship of Jesus and his apostles. They were friends. They could discuss and even argue questions. But such love implies a deeper readiness of understanding, a higher spiritual development than the first. In the Hindu scriptures it is represented in the great conversation of the Bhagavad Gita between the Pandava prince Arjuna and his divine charioteer, the Lord Krishna. The second order of love, then, is that of friend to friend, which in the Christian tradition is typified in the relationship of Jesus and his apostles. They were friends. They could discuss and even argue questions. But such love implies a deeper readiness of understanding, a higher spiritual development than the first. In the Hindu scriptures it is represented in the great conversation of the Bhagavad Gita between the Pandava prince Arjuna and his divine charioteer, the Lord Krishna.

The next, or third, degree of love is that of parent for child, which in the Christian world is represented in the image of the Christmas Crib. One is here cultivating in one's heart the inward divine child of one's own awakened spiritual life — in the sense of the mystic Meister Eckhart's words when he said to his congregation: "It is more worth to God his being brought forth spiritually in the individual virgin or good soul than that he was born of Mary bodily." And again: "God's ultimate purpose is birth. He is not content until he brings his Son to birth in us." In Hinduism, it is in the popular worship of the naughty little "butter thief," Krishna the infant among the cowherds by whom he was reared, that this theme is most charmingly illustrated. And in the modern period there is the instance of the troubled woman already mentioned, supra, p. 100, who came to the Indian saint and sage Ramakrishna, saying, "O Master, I do not find that I love God." And he asked, "Is there nothing, then, that you love?" To which she answered, "My little nephew." And he said to her, "There is your love and service to God, in your love and service to that child."

The fourth degree of love is that of spouses for each other. The Catholic nun wears the wedding ring of her spiritual marriage to Christ. So too is every marriage in love spiritual. In the words attributed to Jesus, "The two shall be one flesh." For the "precious thing" then is no longer oneself, one's individual life, self-transcended in that knowledge. In India the wife is to worship her husband as her lord; her service to him is the measure of her religion. (However, we do not hear there anything like as much of the duties of a husband to his wife.)

And so now, finally, what is the fifth, the highest order of love, according to this Indian series? It is passionate, illicit love. In marriage, it is declared, one is still possessed of reason. One still enjoys the goods of this world and one's place in the world, wealth, social position and the rest. Moreover, marriage in the Orient is a family-made arrangement, having nothing whatsoever to do with what in the West we now think of as love. The seizure of passionate love can be, in such a context, only illicit, breaking in upon the order of one's dutiful life in virtue as a devastating storm. And the aim of such a love can be only that of the moth in the image of Hallaj: to be annihilated in the love's fire. In the legend of the Lord Kishna, the model is given of the passionate yearning of the young incarnate god for his mortal married mistress, Radha, and of her reciprocal yearning for him. To quote once again the mystic Ramakrishna, who in his devotion to the goddess Kali was himself, all his life, such a lover: "When one has loved God in this way, sacrificing all for the vision of his face, 'O my Lord,' one can say, 'now reveal thyself!' and he will have to respond." And so now, finally, what is the fifth, the highest order of love, according to this Indian series? It is passionate, illicit love. In marriage, it is declared, one is still possessed of reason. One still enjoys the goods of this world and one's place in the world, wealth, social position and the rest. Moreover, marriage in the Orient is a family-made arrangement, having nothing whatsoever to do with what in the West we now think of as love. The seizure of passionate love can be, in such a context, only illicit, breaking in upon the order of one's dutiful life in virtue as a devastating storm. And the aim of such a love can be only that of the moth in the image of Hallaj: to be annihilated in the love's fire. In the legend of the Lord Kishna, the model is given of the passionate yearning of the young incarnate god for his mortal married mistress, Radha, and of her reciprocal yearning for him. To quote once again the mystic Ramakrishna, who in his devotion to the goddess Kali was himself, all his life, such a lover: "When one has loved God in this way, sacrificing all for the vision of his face, 'O my Lord,' one can say, 'now reveal thyself!' and he will have to respond."

There is the figure also, in India, of the Lord Krishna playing his flute at night in the forest of Vrindavan, at the sound of whose irresistible strains young wives would slip from their husband's beds and, stealing to the moonlit wood, dance the night through with their beautiful young god in transcendent bliss.

The underlying thought here is that in the rapture of love one is transported beyond temporal laws and relationships, these pertaining only to the secondary world of apparent separateness and multiplicity. Saint Bernard of Clairvaux, in the same spirit, sermonizing in the twelfth century on the Biblical text of the Song of Songs, represented the yearning of the soul for God as both beyond the law and beyond reason. Moreover, the excruciating separation and conflict of the two orders of moral commitment, of reason on one hand, and passionate love on the other, have been a source of Christian anxiety since the beginning. "The desires of the flesh are against the 'Spirit,'" wrote Saint Paul, for example, to the Galatians, "and the desires of the Spirit, against the flesh."

Saint Bernard's contemporary Abelard saw the highest exemplification of God's love for man in the descent of the son of God to the earth to become flesh and his submission to death on the cross. In Christian hermaneutics the crucifixion of the Savior had always presented a great problem; for Jesus, according to Christian belief, accepted death voluntarily. Why? In Abelard's view, it was not, as some in his day had proposed, as a ransom paid to Satan, to "redeem" mankind for his keep; nor was it, as others held, as a payment to the Father, in "atonement" for Adam's sin. Rather, it was an act of willing self-immolation in love, intended to invoke in response the return of mankind's love from worldly concerns to God. And that Christ may not have actually suffered in that loving act we may take from a saying of the mystic Meister Eckhart: "To him who suffers but not for love, to suffer is suffering and hard to bear. But one who suffers for love suffers not, and his suffering is fruitful in God's sight."

Indeed, the very idea of a descent of God into the world of love to invoke, in return, man's love to God, seems to me to imply exactly the contrary to the statement I have just quoted of Saint Paul. Implied, rather, it seems to me, is the idea that as mankind yearns for the grace of God, so God for the homage of mankind, the two yearnings being reciprocal. And the image of the crucified as both true God and true man would then seem to bring to focus the matched terms of a mutual sacrifice — in the way not of atonement in the penal sense, but of at-one-ment in the marital. And further: when extended to symbolize not only the one historic moment of Christ's crucifixion on Calvary, but the mystery through all time and space of God's presence and participation in the agony of all living things, the sign of the cross would then have to be looked upon as the sign of an eternal affirmation of all that is, ever was, or shall be. One thinks of Christ's words reported in the Gnostic Gospel According to Thomas: "Cleave a piece of wood, I am there; lift up the stone, you will find me there." Also those of Plato in the Timaeus, where he states that time is "the moving image of Eternity." Or again, those of William Blake: "Eternity is in love with the productions of time." And there is a memorable passage in the writings of Thomas Mann, where he celebrates man as a noble meeting [eine hohe Begegnung] of Spirit and Nature in their yearning way to each other."

We can safely say, therefore, that whereas some moralists may find it possible to make a distinction between two spheres and reigns — one of flesh, the other of spirit, one of time, the other of eternity — wherever love arises such definitions vanish, and a sense of life awakens in which all such opposites are at one.

The most widely revered Oriental personification of such a world-affirming attitude, transcending opposites, is that figure of boundless compassion already discussed at considerable length, the Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara, known to China and Japan as Kuan Yin, Kwannon. For, in contrast to the Buddha, who at the conclusion of his lifetime of teaching passed away, never to return, this infinitely compassionate one, who renounced for himself eternal release to remain forever in this vortex of rebirths, represents through all time the mystery of a knowledge of eternal release while living. The liberation thus taught is, paradoxically, not of escape from the vortex, but of full participation voluntarily in its sorrows — moved by compassion; for indeed, through selflessness one is released from self, and with release from self there is release from desire and fear. And as the Bodhisattva is thus released, so too are we, according to the measure of our experience of the perfection of compassion. The most widely revered Oriental personification of such a world-affirming attitude, transcending opposites, is that figure of boundless compassion already discussed at considerable length, the Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara, known to China and Japan as Kuan Yin, Kwannon. For, in contrast to the Buddha, who at the conclusion of his lifetime of teaching passed away, never to return, this infinitely compassionate one, who renounced for himself eternal release to remain forever in this vortex of rebirths, represents through all time the mystery of a knowledge of eternal release while living. The liberation thus taught is, paradoxically, not of escape from the vortex, but of full participation voluntarily in its sorrows — moved by compassion; for indeed, through selflessness one is released from self, and with release from self there is release from desire and fear. And as the Bodhisattva is thus released, so too are we, according to the measure of our experience of the perfection of compassion.

It is said that ambrosia pours from the Bodhisattva's fingertips even to the deepest pits of Hell, giving comfort there to the souls still locked in the torture chambers of their passions. We are told, furthermore, that in all our dealings with each other we are his agents, whether knowingly or not. Nor is it the aim of the Bodhisattva to change — or, as we like to say, to "improve" — this temporal world. Conflict, tension, defeats, and victories are inherent in the nature of things, and what the Bodhisattva is doing is participating in the nature of things. He is benevolence without purpose. And since all life is sorrowful, and necessarily so, the answer cannot lie in turning—or "progressing"— from one form of life to another, but only in dissolving the organ of suffering itself, which — as we have seen — is the idea of an ego to be preserved, committed to its own compelling concepts of what is good and what is evil, true and false, right and wrong; which dichotomies — as we have likewise seen — are dissolved in the metaphysical impulse of compassion.

Love as passion; love as compassion: these are the two extreme poles of our subject. They have often been represented as absolutely opposed — physical, respectively, and spiritual; yet in both the individual is torn out of himself and opened to an experience of rediscovered identity in a larger, more abiding format. And in both it is the work of Eros, eldest and youngest of the gods, that we must recognize: the same who in the beginning, as told in the ancient Indian myth, poured himself forth in creation.

In the Occident the most impressive representation of love as passion is to be found in the legend of the love potion of Tristan and Isolt, where it is the paradoxology of the mystery that is celebrated: the agony of love's joy, and the lovers' joy in that agony, which is by noble hearts experienced as the very ambrosia of life. "I have undertaken a labor," wrote the greatest of the great Tristan poets, Gottfried von Strassburg, from whose version of the legend Wagner took the inspiration for his opera, "a labor out of love for the world and to comfort noble hearts: those that I hold dear, and the world to which my heart goes out." But then he adds: "Not the common world do I mean, of those who (as I have heard) cannot bear grief and desire but to bathe in bliss. (May God let them dwell in bliss!) Their world and manner of life my tale does not regard: its life and mine lie apart. Another world do I hold in mind, which bears together in one heart its bitter sweetness and its dear life and sorrowful death, dear death and sorrowful life. In this world let me have my world, to be damned with it, or to be saved."

Do we not recognize here an echo of that same metaphysically grounded sense of a coincidence and transcendence of opposites that we have already found symbolized in the figures of Satan and Hell, Christ on the cross, and the moth consumed in the flame?

However, in the medieval European experience and understanding of love, as interpreted not only by Gottfried and the Tristan poets, but also by the troubadours and Minnesingers of the twelfth and early thirteenth centuries, there is an altogether different tone from anything of the Orient, whether of the Far, Middle, or Near East. Essentially, the Buddhist quality of "compassion," karuna, is equivalent to the Christian of "charity," agape, which is epitomized in the admonition of Christ to love your neighbor as yourself! — and even better, beyond that, in the words that I take to be the highest, the noblest and boldest of Christian teaching: "Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, so that you may be sons of your Father who is in heaven; for he makes his sun to rise on the evil and on the good, and sends rain on the just and on the unjust...."

In all the great traditional representations of love as compassion, charity, or agape, the operation of the virtue is described as general and impersonal, transcending differences and even loyalties. And against this higher, spiritual order of love there is set generally in opposition the lower, of lust, or, as it is so often called, "animal passion," which is equally general and impersonal, transcending differences and even loyalties. Indeed, one could describe the latter most accurately, perhaps, simply as the zeal of the organs, male and female, for each other, and designate the writings of Sigmund Freud as the definitive modern text on the subject of such love. However, in the European twelfth and early thirteenth centuries, in the poetry first of the troubadours of Provence, and then, with a new accent, of the Minnesingers, a way of experiencing love came to expression that was altogether different from either of those two as traditionally opposed. And since I regard this typical and exclusive European chapter of our subject as one of the most important mutations not only of human feeling, but also of the spiritual consciousness of our human race, I am going to dwell on it a little, before proceeding to the final passages of this chapter.

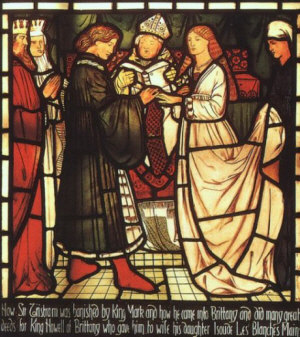

To begin with, then: Marriage in the Middle Ages was almost exclusively a social, family concern — as it has been forever, of course, in Asia, and is to this day for many in the West. One was married according to family arrangements. Particularly in aristocratic circles, young women hardly out of girlhood were married off as political pawns. And the Church, meanwhile, was sacramentalizing such unions with its inappropriately mystical language about the two that were now to be of one flesh, united through love and by God: and let no man put asunder what God hath joined. Any actual experience of love could enter into such a system only as a harbinger of disaster. For not only could one be burned at the stake in punishment for adultery, but according to current belief, one would also burn forever in Hell. And yet love came, even so, to such noble hearts as were celebrated by Gottfried; not only came, but was invited in. And it was the work of the troubadours to celebrate this passion, which in their view was of a divine grace altogether higher in dignity than the sacraments of marriage, and if excluded from Heaven, then sanctified in Hell. And that the word AMOR was the reverse in spelling of ROMA seemed marvelously to epitomize the sense of the contrast.

But wherein, then, lay the special quality of this new order of love, the love that was neither agape nor eros, but amor?

Debates of the troubadours on the subject were a favorite theme of their poems, and the most fitting definition achieved was that which has been preserved to us in a stanza by one of the most respected of their number, Guiraut de Bronelh, to the point that amor is discriminative — personal and specific — born of the eyes and the heart.

-

-

So, through the eyes love attains the heart:

For the eyes are the scouts of the heart,

And the eyes go reconnoitering

For what it would please the heart to possess.

And when they are in full accord

And firm, all three, in the one resolve,

At that time, perfect love is born

From what the eyes have made welcome to the heart.

Not otherwise can love be born or have commencement

Than by this birth and commencement moved by inclination.

To be noted well: such a noble love is not indiscriminate. It is not a "love thy neighbor as thyself no matter who he may be"; not agape, charity or compassion. Nor is it an expression of the general will to sex, which is equally indiscriminate. it is of the order, that is to say, neither of Heaven nor of Hell, but of earth; grounded in the psyche of a particular individual and, specifically, in the predilection of his eyes: their perception of another specific individual and communication of her image to his heart — which is to be (as we are told in other documents of the time) a "noble" or "gentle" heart, capable of the emotion of love, amor, not simply lust.

And what, then, would be the nature of a love so born?

In the various contexts of Oriental erotic mysticism, whether of the Near East or of India, the woman is mystically interpreted as an occasion for the lover to experience depths beyond depths of transcendent illumination — much in the way of Dante's appreciation of Beatrice. Not so among the troubadours. The beloved to them was a woman, not the manifestation of some divine principle; and specifically, that woman. The love was for her, and the celebrated experience was an agony of earthly love: an effect of the fact that the union of love can never be absolutely realized on this earth. Love's joy is in its savor of eternity; love's pain, the passage of time; so that (as in Gottfried's words) "bitter sweetness and dear grief" are of its essence. And for those "who cannot bear grief, and desire but to bathe in bliss," the ambrosial potion of this greatest gift of life is a drink too strong. Gottfried even deified Love as a goddess, and brought his bewildered couple to her hidden wilderness-chapel, known as "The Grotto for People in Love," where stood, in the place of an altar, the noble crystalline bed of love.

Moreover — and this, to me, is the most profoundly moving passage in Gottfried's version of the legend — when, on the ship sailing from Ireland (with which scene Wagner's opera commences), the young couple unwittingly drank the potion and became gradually aware of the love that for some time had been quietly growing in their hearts, Brangaene, the faithful servant who by chance had left the fateful flask unattended, said to them in dire warning, "That flask and what it contained will be the death of you both!" To which Tristan answered, "So then, God's will be done, whether death it be or life. For that drink has poisoned me sweetly. I do not know what the death of which you tell is to be, but this death suits me well. And if delightful Isolt is to continue to be my death this way, I shall gladly court an eternal death." Moreover — and this, to me, is the most profoundly moving passage in Gottfried's version of the legend — when, on the ship sailing from Ireland (with which scene Wagner's opera commences), the young couple unwittingly drank the potion and became gradually aware of the love that for some time had been quietly growing in their hearts, Brangaene, the faithful servant who by chance had left the fateful flask unattended, said to them in dire warning, "That flask and what it contained will be the death of you both!" To which Tristan answered, "So then, God's will be done, whether death it be or life. For that drink has poisoned me sweetly. I do not know what the death of which you tell is to be, but this death suits me well. And if delightful Isolt is to continue to be my death this way, I shall gladly court an eternal death."

What Brangaene had meant was only physical death. Tristan's reference to "this death," however, was to the rapture of his love; and his reference then to "an eternal death" was to an eternity in Hell — which for a medieval Catholic was no mere flourish of speech.

I think of that Moslem figure of Satan, the great lover of God, in God's Hell. And when I recall, furthermore, in the light of these words of Tristan, that scene of Dante's Inferno where the poet, describing his passage through the circle of the carnal sinners, tells of having beheld there, carried past on a burning wind, the whirling, screaming souls of all the most famous lovers of history — Semiramis, Helen, Cleopatra, Paris and yes! Tristan, too; telling of how he had spoken there. Francesca da Rimini in the arms of her husband's brother Paolo, asking what had brought those two to that terrible eternity; and she told him of how they had been reading together of Guinevere and Lancelot and at a certain moment, looking at each other, kissed, all trembling, and read no more in the book that day.... When I recall, as I say, that passage in the light of Tristan's welcome of "an eternal death," I cannot help wondering whether Dante could have been quite correct in regarding the condition of his souls in Hell as of unmitigated pain. His point of view was that of an outsider; one, furthermore, whose own love was bearing him onward and upward to the summit of the highest Heaven. Whereas Paolo and Francesca had the inside point of view of a passion of a much more fiery sort, for a clue to whose terrible joy we may take the word of another visionary, William Blake, in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell: "As I was walking among the fires of Hell, delighted with the enjoyments of genius which to Angels look like torment and insanity...." For the point about Hell — as of Heaven — is this: when there, you are in your proper place, which, finally, is exactly where you want to be.

The same point has been made in Jean-Paul Sartre's play No Exit, where the setting is a hotel room in Hell, sparely furnished in Second Empire style and with an image of Eros on the mantel. Into this single chamber three permanent guests are to be introduced by the bellhop, one by one.

The first, a middle-aged pacifist journalist, has just this minute been shot as a deserter, and what his pride now most requires is to be told that his attempt to escape to Mexico and publish there a pacifist magazine was heroic; he was not a coward. The second to be ushered in, then, is a Lesbian who lost her life when a young wife whom she had seduced turned on the gas secretly in her apartment and expired with her, asphyxiated, in bed. Immediately despising the craven male who is to be her companion here forever, this coldly intellectual female gives him no comfort whatsoever in his need. Nor can the next and final entrant, a man-crazy young thing who had drowned her illegitimate child and driven her lover to suicide.

This second female, of course, becomes immediately interested in the male, who requires, however, not passion but compassion. The Lesbian blocks every attempt they make to reach some kind of accord, making moves of her own, meanwhile, toward the other female, who has neither any interest in, nor understanding of what she wants. And when these three — so exquisitely matched — have brought their unrelenting demands on each other to such a pitch of frustration that escape, one way or the other, would seem to be the only thing that anyone in such a spot could desire, the locked door of their room swings open — showing an azure void — and nobody leaves. The door swings shut, and they are locked forever in their chosen cell.

Bernard Shaw says much the same in Act III of his Man and Superman: that delicious scene where a little old lady, faithful daughter of Mother Church, is informed that the landscape through which she is happily strolling is not of Heaven but Hell. She is indignant. "I tell you, I know I am not in Hell," she insists, "because I feel no pain." Well, if she likes (she is told), she can easily stroll on over the hill into Heaven. However, the strain of remaining there has been found intolerable (she is warned) for those who are happy in Hell. There are a few — and they are mostly English — who nevertheless remain, not because they are happy, but because they think they owe it to their position to be in Heaven. "An Englishman," states her informer, "thinks he is moral when he is only uncomfortable." And with that telling Shavian quip, I am carried to my final reflections on this chapter's theme.

For it was in the legend of the Holy Grail that the healing work was symbolized through which the world torn between honor and love, as represented in the Tristan legend, was to be cured of its irresolution. The intolerable spiritual disorder of the period was represented in this highly symbolic tale in the figure of a "waste land" — the same that T.S. Eliot in his poem of that name, published in 1922, adopted to characterize the condition of our own troubled time. Every natural impulse in that period of ecclesiastical despotism was branded as corrupt, with the only recognized means of "redemption" vested in sacraments administered by authorities who were themselves indeed corrupt. People were forced to profess and live by beliefs they did not always actually hold. The imposed moral order held precedence over the claims of both truth and love. The pains of Hell were illustrated on earth in the torture of adulteresses, heretics, and other villains, torn apart or set afire in public squares. And all hope of anything better was pitched high aloft to that celestial estate of which Gottfried spoke with such scorn, where those who could bear neither grief nor desire were to be bathed in a bliss everlasting.

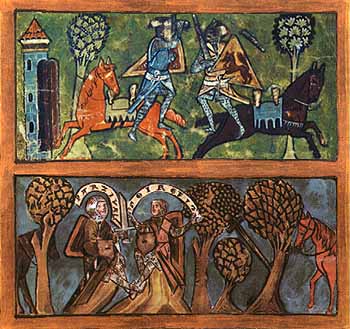

In the legend of the Grail, as rendered in the Parzival of Gottfried's very great contemporary and leading literary rival, Wolfram von Eschenbach, this devastation of Christendom is symbolically attributed to the awesome wounding of the young Grail King Anfortas, the meaning of whose name is "infirmity"; and the expected issues of the awaited Grail Knight was to be the healing of this dreadfully wounded youth. Anfortas — significantly — had only inherited, not rightly earned, the high office of guardianship of the supreme symbol of the spiritual life. He had not, that is to say, been properly proven to his role, but instead still moved in the natural way of youth. And like all noble youths of that period, he rode forth one day from the Castle of the Grail with the battle cry "Amor!" And he encountered immediately a pagan knight from a land not far from the walled garden of Paradise, who had come riding in quest of the Grail and with its name engraved on his spearhead. The two settled their lances, rode at each other, and the pagan knight was slain. But his lance, inscribed with the name of the Grail, had already unsexed the young king, and its head, broken off, remained in the excruciating wound. In the legend of the Grail, as rendered in the Parzival of Gottfried's very great contemporary and leading literary rival, Wolfram von Eschenbach, this devastation of Christendom is symbolically attributed to the awesome wounding of the young Grail King Anfortas, the meaning of whose name is "infirmity"; and the expected issues of the awaited Grail Knight was to be the healing of this dreadfully wounded youth. Anfortas — significantly — had only inherited, not rightly earned, the high office of guardianship of the supreme symbol of the spiritual life. He had not, that is to say, been properly proven to his role, but instead still moved in the natural way of youth. And like all noble youths of that period, he rode forth one day from the Castle of the Grail with the battle cry "Amor!" And he encountered immediately a pagan knight from a land not far from the walled garden of Paradise, who had come riding in quest of the Grail and with its name engraved on his spearhead. The two settled their lances, rode at each other, and the pagan knight was slain. But his lance, inscribed with the name of the Grail, had already unsexed the young king, and its head, broken off, remained in the excruciating wound.

This calamity, in Wolfram's meaning, was symbolic of the dissociation within Christendom of spirit from nature; the denial of nature as corrupt, the imposition of what was supposed to be an authority supernaturally endowed, and the actual demolishment of both nature and truth in consequence. The healing of the maimed king, therefore, could be accomplished only by an uncorrupted youth naturally endowed, who would merit the supreme crown through his own authentic life work and experience, motivated by a spirit of unflinching noble love, enduring loyalty, and spontaneous compassion. Such a one was Parzival. And though we cannot in these few pages review the whole course of his symbolic career, enough can be said of four of the main episodes to suggest the burden of the poet's healing message.

The noble youth had been reared by his widowed mother in a forest aloof from the courtly world, and it was only when he chanced to see a small company of questing knights go riding past his farm that he learned of knighthood and, abandoning his mother, set forth for King Arthur's court. His training in courtesy and in the skills of knightly combat he received from Gurnemanz, an old nobleman who admired his obvious qualities and offered him his daughter in marriage. But Parzival, thinking, "I must not simply accept, I must earn, my wife!" courteously, gently refused the gift and, alone again, rode away.

He let the reins lie slack on his charger's neck, and was thus carried by the will of nature (his mount) to the besieged castle of an orphaned queen his own age, Condwiramurs (conduire amour) whom he next day heroically rescued from the undesired assaults of a king who had hoped to add her feudal estates through capture and marriage to his own. And it was she, then, that lovely young queen, who became the wife he had earned; and there was no priest to solemnize the marriage — the poet Wolfram's healing message here being that noble love alone is the sanctification of marriage, and loyalty in marriage, the confirmation of love.

Proposition two, to which the poet then addressed himself, was of human nature fulfilled — not overcome or transcended — in the achievement of that supreme spiritual goal of which the Grail was the medieval symbol. For it was only after Parzival had met the normal secular challenges of his day — both in knightly deeds and in marriage — that he became involved without either forewarning or intent in the unpredicted, unpredictable context of the higher spiritual adventure symbolized in the Grail Castle and wondrous healing of its king. The mystical law governing the adventure required that the hero to achieve it should have no knowledge of its task or rules, but accomplish all spontaneously on the impulse of his nature. The castle would appear like a vision before him. Its drawbridge lowering, he would ride across it to a joyous welcome. And the task then expected of him, when the maimed king on his litter would be carried into the stately hall, would be simply to ask what ailed him. The wound would immediately heal, the waste land become green, and the saving hero himself be installed as king. However, on the occasion of his first arrival and reception, Parzival, though moved to compassion, politely held his peace; for he had been taught by Gurnemanz that a knight does not ask questions. Thus he allowed concern for his social image to inhibit the impulse of his nature — which, of course, was exactly what everyone else in the world was doing in that period and was the cause of all that was wrong.

Well, to cut a long and wonderful story very short, the result of this suppression of the dictate of his heart was that the young, misguided knight — scorned, humiliated, cursed, derided, and exiled from the precincts of the Grail — was so shamed and baffled by what had happened that he bitterly cursed God for what he took to have been a mean deception practiced upon him, and for years he rode in desperate, solitary quest, to achieve again that castle of the Grail and release its suffering king. Indeed, even after learning from a forest hermit that it was God's law of that enchantment that none seeking the castle would find it and none who had failed once should ever have a second chance, the resolute youth persisted, moved by compassion for its terribly maimed king, whom his failure had left in such pain.

But his ultimate victory followed, ironically, rather from his loyalty to Condwiramurs and fearlessness in combat than from his obdurate determination to rediscover the castle. The immediate occasion was a great and gallant wedding feast — with many a fair lady thereabout and much fashionable dalliance among colorful pavilions — from which he rode away, not in moral dudgeon but because, with the image of Condwiramurs in his heart (whom he had not seen through all these cruel years of unrelenting quest), he could not bring himself to engage in any of the pleasures of that marvelously fair occasion. He rode away alone. And he had not ridden far when there came charging at him from a nearby wood a brilliant knight of Islam.

Now Parzival had known for some time that he had an elder half-brother, a Moslem; and it happened that this was he. They clashed and gave battle fiercely, "And I mourn for this," wrote Wolfram; "for they were the two sons of one man. One could say that 'they' were fighting, if one wished to speak of two. Those two, however, were one.: 'My Brother and I' is one body, like good man and good wife. Contending here from loyalty of heart, one flesh, one blood, was doing itself much harm."1 The battle scene is a recapitulation transformed of the encounter of Anfortas with the pagan. Parzival's sword, however, here broke on the other's helmet. The Moslem flung his own blade away, scorning to murder a defenseless knight, and the two sat down to what proved to be a recognition scene.

Clearly implicit in this critical meeting is an allegorical reference to the two opposed religions of the time, Christianity and Islam: "two noble sons," so to say, "of one father." And marvelously, when the two brothers have found their accord, a messenger of the Grail appears to invite both to the castle — which in a Christian work of the time of the Crusades is a detail surely remarkable! The maimed king is healed, Parzival is installed in his stead, and the Moslem, taking the Grail Maiden to wife (in whose virgin hands alone the symbolic vessel had been carried), departs with her to his Orient, there to reign in truth and love — seeing to it (as the text declares) "that his people should gain their rights."

But this wonderful Parzival of Wolfram von Eschenbach simply has to be read.2 Humorous, joyous, altogether different both in spirit and in meaning from the ponderous opus of Richard Wagner, it is one of the richest, greatest, most civilized works of the European Middle Ages; and as a monument, moreover, to the world-saving power of love in all its forms, perhaps the very greatest love story of all time.

So let me now, in conclusion, turn to the writings of an author of our own day, Thomas Mann, who already in his earliest novelette, Tonio Kröger, named love the controlling principle of his art.

The young North German hero of this story, whose mother was a woman of Latin race, found himself set apart from his blue-eyed blond companions, not only physically, but also temperamentally. It was with a curiously melancholy strain of intellectual contempt that he regarded them; yet with envy also, mixed of admiration and love. Indeed, in his secret heart, he pledged himself to them all eternally — and particularly a certain charming blue-eyed Hans and beautiful blond Ingeborg, who represented to him irresistibly the appeal of fresh human beauty and youthful life.

On coming of age, Tonio left the north to seek his destiny as a writer, and, moving to a city of the South, met there a young Russian, Lisaveta by name, and her circle of heavy thinkers. He there found himself no more at home, however, among those critics and despisers of the commonalty of the human race, than he had formerly felt among the objects of their scorn. He was thus between two worlds, "a lost burgher," as he termed himself; and departing from this second scene mailed back, one day, to the critical Lisaveta and epistolary manifesto, setting forth his credo as an artist.

The right word, le mot juste, he had recognized, can wound; can even kill. Yet the duty of the writer must be to observe and to name exactly: wounding, even possibly killing. For what the writer must name in describing are inevitably imperfections. Perfection in life does not exist; and if it did, it would be — not lovable but admirable, possibly even a bore. Perfection lacks personality. (All the Buddhas, they say, are perfect, perfect and therefore alike. Having gained release from the imperfections of this world, they have left it, never to return. But the Bodhisattvas, remaining, regard the lives and deeds of this imperfect world with eyes and tears of compassion.) For let us note well (and here is the high point of Mann's thinking on this subject): what is lovable about any human being is precisely his imperfections. The writer is to find the right words for these and to send them like arrows to their mark — but with a balm, the balm of love, on every point. For the mark, the imperfection, is exactly what is personal, human, natural, in the object, and the umbilical point of its life.

"I admire," wrote Tonio Kröger to his intellectual friend, "those proud and cold beings who adventure on paths of great daemonic beauty and despise 'mankind'; but I do not envy them. Because {and here he lets fly his own dart} if there is anything capable of making a poet of a literary man, it is this burgherlike love that I feel for the human, the commonplace. All warmth, goodness, and humor derives from this; and it even seems to me that it must be itself that love of which it is written that one may speak with the tongues of men and of angels and yet, having it not, be as sounding brass and tinkling cymbals..."

"Erotic" or "plastic irony," is the name that Thomas Mann bestowed on this principle; and through the greater part of his creative career it was the guiding principle of his art. The unflinching eye detects, the intellect names, the heart goes out in compassion; and the life-force of every life-loving heart will be finally tested, challenged, and measured by its capacity to regard with such compassion whatever has been by the eye perceived and by the intellect named. "For God," as we read in Paul to the Romans, "has consigned all men to disobedience, that he may show his mercy to all."

Moreover, life itself, we can be sure, will provide every one of us ultimately with a test of our capacity for such love — as it in time tested Thomas Mann, with its transformation of his blue-eyed Hans and blonde Ingeborg, under Hitler, into what he could only name and describe as depraved monsters...

What does one do under such a test?

Saint Paul has said, "Love bears all things." We have the words also of Jesus: "Judge not that you may not be judged." And there is the saying, too, of Heraclitus: "To God all things are fair and good and right; but men hold some things wrong and some right. Good and evil are one."

There is a deep and terrible mystery here, which we perhaps cannot, or possibly simply will not, comprehend; yet which will have to be assimilated if we are to meet such a test. For love is exactly as strong as life. And when life produces what the intellect names evil, we may enter into righteous battle, contending "from loyalty of heart": however, if the principle of love (Christ's "Love your enemies!") is lost thereby, our humanity too will be lost.

"Man," in the words of the American novelist Hawthorne, "must not disclaim his brotherhood even with the guiltiest."

Return to Passages Menu

Subscribe to the Passages e-zine

|