|

'Tis the season. No need to ask which. After all, it is such an immutable and consistent part of the rhythm of our lives that each of us knows in our bones when Christmas arrives: The day after Halloween. No! Sorry. I have been spending too much time at the mall. The date of Christmas is, as everybody knows, December 25th. This is all well and good. It is a dark, cold time of the year, and all of us could use some holiday cheer. It is not, however, the date of the birth of Christ. This too would be fine, but the date of the birth of Christ serves as the anchor point, reason and basis for our calendar, and it can be unsettling to realize that the clock we have imposed on our lives has, to put it gently, a checkered past.

Where Christmas Falls

Also:

Caesar, Tropical Year, time travel, cuneiform, Brahmasphutasiddhant, Mesopotamians, sports agents, zero, questionable logic.

Copyright © 2006 by Zachariah Hill

Zachariah Hill calls himself a "renegade Jew from Bennington College."

You may not have heard of this particular episode in America's illustrious history, but on Thursday, September 14th, 1752, the native populace of the colonies woke up and discovered that every single one of them had been asleep since September 2nd.

It was alarming, to say the least. After all, went the thinking, a man has only so many days to live, and here we have all missed 11 of them! Needless to say, there was a great deal of civic unrest, rioting even, and several people were killed (and also earned a place among the most ironic deaths in colonial history, for being killed while protesting the loss of several days of their life).

That it happened at all was probably Sosigenes' fault.

It was, after all, Sosigenes who convinced Julius Caesar to make the year 46 BC 455 days long. This was the kind of crazy thing that you could never get away with today, but was always going on in the years BC. Power was distributed somewhat differently than today, and a good part of the world operated on the whatever-Caesar- feels-like system of government. If Caesar decided that 46 BC would have 455 days, then everyone was fine with that, and if they had a problem, they could keep it to themselves, or they could be nailed by the wrists and ankles to a cross, and hung there suffocating and slowly being eaten by birds.

So nobody much argued with Caesar about this one, and it turns out he had a perfectly good reason for giving the decree. Caesar was trying to reform the Roman calendar, and if the seasons were finally going to match up to the calendar, 46 BC had to have 455 days, after which each year would have 365 days, except for each fourth year, which would have 366. In retrospect, he probably should have been clearer about what he meant by every fourth year, because someone finally realized in 9 BC that Roman priests had been adding a leap year every three years, not four, and so they couldn't have any more leap years until 8 AD. But it was a good first effort.

It is important to note that Caesar did not refer to the year as 46 BC. The Romans used a calendrical system which calculated its date from the founding of Rome. Caesar's 455 day-long year would not become known as 46 BC until 527 AD.

When it finally did, it was because Pope John I was having an hell of a time getting people to celebrate Easter, and much of this had to do with the fact that because of inconsistencies in the calendar, no one really knew when Easter was going to be.

To remedy the situation, he contracted Dionysius Exiguus (literally, Dennis the Small) to help him pinpoint the dates of the next 100 Easters. In doing so Dionysius decided that he needed a new reference point for his reckoning, and chose a date 753 years from the founding of Rome.

To remedy the situation, he contracted Dionysius Exiguus (literally, Dennis the Small) to help him pinpoint the dates of the next 100 Easters. In doing so Dionysius decided that he needed a new reference point for his reckoning, and chose a date 753 years from the founding of Rome.

This was the year that, according to his calculations, Jesus Christ was born during, and he dubbed this the year one. The system had a bright future, but wasn't widely used at first, and it took the pervasive spread of Christianity to bring it to much of the world. It was not until about 1000 AD (or about 470 years after its invention, this was not an overnight success story) that most of the West had accepted it.

We continue to accept it to this day, and we utilize it for a lot of important things, such as marking the date of the birth of God's son, or calculating when he will return and bring Armageddon with him. Unfortunately, for those trying to date these types of things, or for those poor unfortunates killed in the riots of 1752, there were three very important things that Dionysius did not know.

The first was that the Julian method of calculating the length of a year was off. Chronological Scientists now know that the length of a year is about 365.242190 days, not 365. The resulting error caused the calendar to move ahead of the actual tropical year (the technical term for what we call a year, which is defined as the amount of time it takes the Earth to move all the way around the sun, and back to whatever starting position you have chosen for it, once).

The amount of extraneous days works out to about eight every 1,000 years. This may not seem like much, but by 1582, the calendar was 10 days ahead, and Pope Gregory XIII had decided that those days would simply be gotten rid of. This marked the West's conversion to the Gregorian calendar, so-named because it was developed by the astronomer Christopher Clavius. The result of this conversion was that every Catholic Country in Europe skipped overnight from the 4th to the 15th of March.

But if this was not enough to cause confusion, the real hilarity begins when one recognizes that by this time the Protestant reformation has been underway for some time, and there are all sorts of Anglicans, Lutherans, Calvinists, Puritans, etc, who have no use for the Papists at all, and are not about to let any Pontiff, Gregory or otherwise, tell them what to do. The result was that 'what day it is' became largely dependent on the current religious affiliation of your country. It was possible, given the political situation in Europe in the late 16th century, to traverse the continent, constantly skipping back and forth in time as you crossed borders, arrive somewhere more than a week before you left, and to do it all with nothing but a horse or sturdy pair of boots. Much of the rest of the world would eventually all convert to the Gregorian system, and among the very last to do so was America, on September 14th, 1752 (or, if you were one of those rioting, what should have been September 3rd). Thus, Sosigenes's eventual responsibility for the death of those colonists.

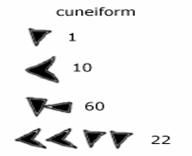

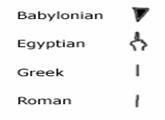

The second thing that Dionysius did not know is what we blame all those self-righteous know-it-alls who kept wandering around during the end of the millennium celebrations. You know the ones...they kept insisting that the new millennium would not be starting until 2001 and ruining everybody's fun. There is evidence that as early as 3000 BC fairly sophisticated methods of calculation existed. Numerals had been in use for some time, but these had more in common with something like Kanji, in which there is a symbol for each word, or in this case number, than the alphanumeric we use today. But by 3000, the Mesopotamians were moving toward the first modern numerical system. Cuneiform, as it was called, used a series of wedge shaped figures, which could be combined in different ways to form numbers. Here is a graphical reproduction:

Historians agree that these particular shapes were used because "the Mesopotamians used a stick, which, when pressed into a wet clay tablet, made wedge-shaped marks." (Moteaco, 35) This does not really explain the system for me, but maybe there was only one stick, shaped just like that, and they had to take turns using it or something. It's not really important why this particular system was used, what is important is that it is the predecessor of our own, as is obvious from this illustration:

Or, at least, it is obvious to the same historians who told us about the stick. We should move on. But even if we say the derivation of the Roman numerals for one and five are both readily apparent from the figure above, what is more difficult is figuring out from where in all this we derived zero. Go ahead, try writing the Roman numeral for zero. The reason it is so hard is that the concept of zero did not exist yet.

Actually, the previous statement is not really true, but it is an understandable misstatement, because of the complicated nature of zero.

The complication arises when we recognize the concepts 234 and 2304 have always been significantly different, even though they contain the same numerals (two, three, and four), in the same order. A placeholder was needed to visually represent the difference. Thus, zero was first used as a punctuation mark: 23"4, essentially.

Interestingly, it seems that the Mesopotamians used zero only inside a numeral, and never at the end. You may wish to point out that this would make the writing of a number like 260 impossible, and indistinguishable from 26. You would be right. Historians speculate that the difference was inferred by the Mesopotamian reader based on context, but you can just imagine all kinds of situations like some Mesopotamian athlete ending up very, very disappointed in his agent after discovering that he had actually signed that contract for 12 after all. One would think that someone would eventually get drunk one night and recklessly tack a zero onto the end of a number, just for the heck of it, but apparently no one ever did. But ending a numeral was not the only thing that zero was not used for. There was also no mathematical concept corresponding to naught, or not any.

At least not until around 598 AD. Brahmagupta, the brilliant son of Jisnugupta, was born in Hindustan on this date, and his genius would eventually lead to some of the most unpronounceable works of mathematics in history, such as the Brahmasphutasiddhanta and the Khandakhadyaka. But they were also groundbreaking. His first insight:

The sum of zero and zero is zero.

Later, he moved on to more complicated mathematical tools:

Zero subtracted from zero is zero.

And after a bit more thought, in a later publication:

... a number multiplied by zero is zero.

And finally, feeling that he was on a roll:

Zero divided by zero is zero.

It turned out later that this last one was incorrect, but his contribution to mathematics cannot be overestimated. It is possible that despite Brahmagupta's brilliance, you have never heard of him. This is because it took a long time for the concept to make its way west. Not until around 1200 AD did one Leonardo Pisano begin to popularize it. Pisano is better known today by his nickname, Fibonacci, which means, literally, 'son of Bonacci.' Of course, his father was Geilielmo Bonacci, so, nickname-wise, it was accurate. Fibonacci himself preferred to be called Bigollo, and often used the name, which means good-for-nothing. This nickname is less accurate, because Fibonacci would, in the second section of his brilliant mathematical treatise Liber Abaci, have mankind's single most important insight into rabbit sex. He posed the question:

A certain man put a pair of rabbits in a place surrounded on all sides by a wall. How many pairs of rabbits can be produced from that pair in a year if it is supposed that every month each pair begets a new pair which from the second month on becomes productive?

The answer is: 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55.... and on into infinity. Close examination of this sequence reveals that adding any two terms yields the next term. 1 + 1 = 2, 1 + 2 = 3, 2 + 3 = 5, etc. This sequence, which at first glance seems merely interesting, has actually proven to be incredibly useful in many aspects of mathematics and science. A mathematical journal, the Fibonacci Quarterly, is entirely devoted to the ramifications of examining it. It was during such an examination that Fibonacci began using zero as a symbol meaning naught, and bringing Brahmagupta's breakthroughs west.

But the thirteenth century AD was well after Dionysius Exiguus' time, which brings us back to the second thing that Dionysius did not know about: the number zero. The result is that the Roman calendar, the very same one we use today, has no year zero, but skips straight from 1 BC to 1 AD. This should help clarify when the second millennium actually began. Two thousand years after 1 AD is 2001, which is in fact when the new millennium got under way.

Now in Dionysius' time, the Bible did not have the ubiquitous presence that it has today, and it is entirely possible that he had never read it. This, together with the fact that archeological records and historical data were not really available to him, and had not, technically, even been converted into historically significant ruins or artifacts, may explain the Dionysius' last mistake. It turns out that the third thing Dionysius did not have the least idea about was when Jesus was born.

Biblical scholars and historians cannot settle on a date, or even a year, for the birth of Christ, and it is too much to get into here. I can, however, offer you Dionysius's reasoning.

In Dionysius' day, it was tradition that the crucifixion occurred on March 25th. Why is unclear, but let's move on. It was also tradition that holiness was equivalent to perfection. Perfection was equivalent to completion, and completion to wholeness. Just go with it. Jesus was the son of God, so it doesn't get any holier, and for that reason, he must have lived a perfectly whole number of years. Therefore, he must have died on the same day that he was conceived. (If you were thinking to yourself that he must have died on the day he was born, you are obviously not a pro-lifer.) A perfect nine months after a conception on March 25th (the day of his death) would place Jesus' birth on December 25th, which probably sounds familiar.

This was how Dionysius presents his argument, anyway. If there is one thing that is clear by now, it is that what December 25th meant to Dionysius is almost impossible to say, and this is without questioning the logic Dionysius employed to get there.

Like almost everything about the modern Christmas, little about "the season" is historically substantial. What at first seems odd is that so many fervently religious people choose not to question. In the stark reality of midwinter, it seems less so. Lacking any real excuse to celebrate, give, and encourage peace in our darkest hours, we made one up. Which reassures me.

Return to Mythic Passages Menu

Subscribe to the Mythic Passages e-magazine

|