|

Part 1: Mythologies of the Primitive Hunters and Gatherers

from Historical Atlas of World Mythology

© Joseph Campbell, 1988

and used with permission of the Joseph Campbell Foundation

The Landscape of the Great Hunt

The landscape of the "Great Hunt," typically, was of a spreading plain, cleanly bounded by a circular horizon, with the great blue dome of an exalting heaven above, where hawks and eagles hovered and the blazing sun passed daily; becoming dark by night, star-filled, and with the moon there, waning and waxing. The essential food supply was of the multitudinous grazing herds, brought in by the males of the community following dangerous physical encounters. And the ceremonial life was addressed largely to the ends of a covenant with the animals, of reconciliation, veneration, and assurance that in return for the beasts' unremitting offering of themselves as willing victims, their life-blood should be given back in a sacred way to the earth, the mother of all, for rebirth.

Out of One, the Many

(Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, 1.4.1-5)

The following text is from the earliest of the Upanishads, the Brihadaranyaka, which is of a date somewhere about the ninth century B.C., and thus about contemporary with the biblical legend in Genesis 2 of God producing Eve from Adam's rib.

In the beginning, there was only the Great Self in the form of a Person. Reflecting, it found nothing but itself. Then its first word was: "This am I!" whence around the name "I." Which is why, to this day, when one is addressed, one first says, "I," then tells whatever other name one may have...

That one was afraid. Therefore anyone alone is afraid. "If there is nothing but myself," it thought. "Of what, then am I afraid?" Whereupon the fear departed. For what was there to fear? Surely, it is only from a second that fear derives.

That Person was no longer happy. Therefore, people are not happy when alone. It desired a mate. It became as large as a woman and man in close embrace; then caused that Self to fall in two: from which a husband and wife arose. (Therefore, as the sage Yajñavalkya used to say, this body is but half of oneself, like the half of a split pea; which is why this space is filled by a wife.) He united with her; and from that human beings were born.

She thought: "How can he unite with me, after producing me from himself? Well, let me hide." She became a cow, he a bull, and united with her. From that cattle were born. She became a mare, he a stallion; she a she-ass, he a he-ass; and united with her. From that one-hoofed beasts were born. She became a she-goat, he a he-goat; she became a ewe, he a ram; and he united with her. From that goats and sheep were born. In this way he projected all things existing in pairs, down to the ants.

Then he realized: "I, indeed, am this creation; for I have poured it forth from myself." In that way he became this creation. And verily, he who knows this becomes in this creation a creator.

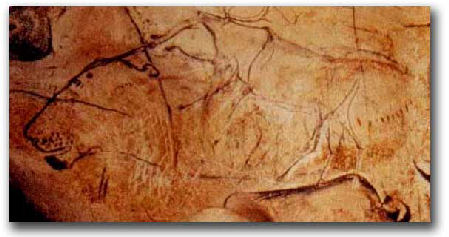

The Shamans of the Caves

Neither in body nor in mind do we inhabit the world of those hunting races of the Paleolithic millennia, to whose lives and life ways we nevertheless owe the very forms of our bodies and structures of our minds. Memories of their animal envoys still must sleep, somehow, within us; for they wake a little and stir when we venture into wilderness.

They wake in terror to thunder. And again they wake, with a sense of recognition, when we enter any one of those great painted caves. Whatever the inward darkness may have been to which the shamans of those caves descended in their trances, the same must lie within ourselves, nightly visited in sleep. Moreover, in parts of the world marginal to contemporary civilization, the beat of the shaman's drum may still be heard, transporting spirits in flight to regions known to our own visionaries and to men and women gone mad. Did the shamans of those caves interpret their visionary voyages as shamans do today—shamans whom we can visit and with whom many of us have conversed? Our only evidence is the pictorial script in the labyrinthine secrecy of the silent caves themselves. Why so deeply hidden and, in parts, so difficult of access?

"Some caves with animal art," as Alexander Marshack has remarked, "are so difficult to get into and their painted and engraved chambers are so deep that hours were spent climbing inside, time was spent in engraving, painting, and ceremony, and more time was spent coming out. This would be a tiring and uneconomic activity for a hunter performing hunting magic! In true hunting magic, one can draw the animal in the sand or scratch it on an open rock surface and perform the rite of magic killing quickly."

The Bushman Trance Dance and Its Mythic Ground

The Bushmen's gods, seriously regarded, are very different from this folktale character. Lorna Marshall found that the Kung of Botswana were afraid even to utter their gods' names. "We were aware," she tells, "of their unwillingness to speak of religious matters early in our work and therefore waited until our relations were well established before questioning them.... Sometimes we talked literally in whispers and usually at least in low voices, saying 'the one in the east,' 'the one in the west.' ...The woman who first told me the name of the wife of the great god put her lips to my ear and whispered,barely audibly, 'Huwedi!' Next day, unfortunately, she had a high fever. She recovered, but the episode put an end to my trying to learn from her about the wives of the gods."

According to this authority, the Kung today have two gods: one, the great, in the east, where the sun rises; one, the lesser, in the west, where it sets. Both have wives and are attended by the spirits of the dead. The great god created first himself, then the lesser god, then their wives, each of whom bore three girls and three boys. He also created the earth, its people, and all things. To praise himself, the great god named himself, saying, "I am Hishe. I am unknown, a stranger. No one can command me." He praised himself with a number of names: Gara, for example, when he did things hurtful to people. "He causes death among us," the people then would say. "He causes rain to thunder." Or, again he would declare: "I am Gaishi gai, a bad thing. I take my own way. No one can advise me." To the lesser god he gave all of his own names but one, the oldest, the human name, with which he appears in the folktales: Gao na, "Old Gao." And to the wives he gave all of his divine names in their feminine forms: Hishedi, Gaishi gaidi, and so on, but each also had her own human name, which can be pronounced aloud without fear.

As Old Gao, the great god is at once himself and not himself, and the people tell his old tales without restraint. They say his name aloud and even howl and roll on the ground with laugher at his humiliations. "Like men, " states Lorna Marshall, "he was subject to passions, hungers, sins, stupidities, failures, frustrations, and humiliations, but men imagine his to have been on a larger scale and more grotesque than their own. Like Bushmen of today, his great concerns were hunger and sex. To the Kung the two worst sins, the unthinkable, unspeakable sins, are cannibalism and incest. Old Gao committed both these sins unconcernedly. He ate his older brother-in-law and his younger brother-in-law, and he raped his son's wife."

In the Cape Bushman legend of Kaggen and the first eland, the same duplicity is evident as in the Kung tales of Old Gao. The narratives carry, behind a protective screen of radically reductive metaphor, reflexes of the greatest mysteries. It has been noticed, for example, that the shoe can be understood as symbolic of the vagina, and honey, as of semen. The shoe of Kaggen's son-in-law, then, would have been the organ of Kaggen's daughter, and the honey fed it as an eland, his own procreative seed. In another version: Kaggen's wife bore the first eland and Kaggen tried to kill it by throwing sharpened sticks, but he missed. Then he left (again for three days) to fetch arrow poison, and while he was gone, his sons discovered and killed the eland. Returning, he rebuked them furiously. But then he and his wife mixed fat from the animal's heart in a pot, together with some of its blood, and churned. The drops became first, eland bulls, then cows, which spread over the earth. Whereupon Kaggen sent his sons out to hunt them. And that day, game were given to men to eat.

The hunter's need to kill in order to live is justified in this legend as an institution of the First Being himself; and the god's ambiguous relationship both to the animal slain and to its killing is our clue to what in literary criticism would be termed the anagogical meaning of the tale. The arrow shot at those butchering his eland turns back and nearly strikes the god himself. While in the second telling of his tale, it is he who is the first to attempt the kill. In the first version he went off to find honey; in the second, to get poison. The apparent equivalence here of the god's life-giving and death-dealing powers cannot be accidental.

Kaggen's creation of the moon after his eland has been butchered is another significant sign. One shoe had become his eland; the other became the moon: the two being equally endowed with the power of rebirth. Moreover, to procure the required honey or poison, Kaggen left the scene for three days: the moon is three nights dark. And when he returns to find his eland dead, he is through his own act covered with darkness—until the new moon appears.

Patricia Vinnicombe calls attention to the Bushmen's use of blood and fat as components of their paints. Herbert Kuhn has suggested that blood and fat may have been ingredients of the paints of the European caves. Thus the act of painting may have been, as Vinnicombe suggests, a ritual act of restitution in the very sense of the restitution and multiplication of Kaggen's eland in the second version of his legend. "It seems reasonable," she writes, "to postulate that the Bushman artist played an important role in this propitiation ceremony, and that by recreating visible eland upon the shelter walls, Man the Hunter was reconciled with Kaggen the Creator, thereby restoring the balance of opposing forces that was so necessary for the well-being of the Bushman psyche. Through the eland, the Bushman established and maintained communication with his god. Through the eland, the eternal cycle of sacrificing life in order to conserve and promote life was ritually expressed." In sum, the mythological eland sacrifice, of which every hunting kill is a duplication, is the inexhaustible vessel out of which the bounty of the great god's world proceeds. And every hunter, in his sacrificial killing, is in the role of Kaggen himself, identified with the animal of his kill and at the same time guilty, as the god is guilty, with the primordial guilt of life that lives on life.

Joseph Campbell; Historical Atlas of World Mythology, Part One: Mythologies of the Primitive Hunters and Gatherers; HarperCollins, 1988

- The Landscape of the Great Hunt: pg 9

- Out of One, the Many: pg 13

- The Shamans of the Caves: pg 73

- The Bushman Trance Dance and Its Mythic Ground: pg 91 - 94

Return to Passages Menu

Subscribe to the Passages e-zine

|