|

Bringing Death Back Home

By Marilyn Strong

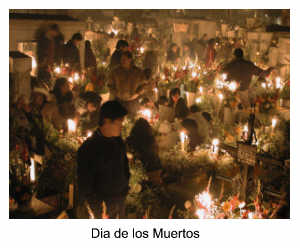

I recently returned from a gathering at Mountain Home Ranch Resort, located in the hills of wine country between Napa and Sonoma Valleys in northern California. The focus of this gathering was a training called Honoring Life's Final Passage with Love and Compassion: Death Midwifery Level III. It was taught by Jerrigrace Lyons, Founder and Director of Final Passages, an educational non-profit program founded in 1995 and dedicated to dignified and compassionate alternatives to current funeral practices. For eleven years she has offered her services to the community and beyond, helping 250 families plan and create their own home funerals. She also teaches workshops, consults and sells informative guides and pamphlets. Thirty-five of us from six different states gathered at a most appropriate time of year for this training — early November, during what the Mexicans call Los Dias de Muertos or Days of the Dead, Mexico's traditional holiday honoring departed ancestors, friends and family. This is a time in the wheel of the year when the "veil between the worlds is thin," and it felt to be an auspicious time to further my training in Death Midwifery! I recently returned from a gathering at Mountain Home Ranch Resort, located in the hills of wine country between Napa and Sonoma Valleys in northern California. The focus of this gathering was a training called Honoring Life's Final Passage with Love and Compassion: Death Midwifery Level III. It was taught by Jerrigrace Lyons, Founder and Director of Final Passages, an educational non-profit program founded in 1995 and dedicated to dignified and compassionate alternatives to current funeral practices. For eleven years she has offered her services to the community and beyond, helping 250 families plan and create their own home funerals. She also teaches workshops, consults and sells informative guides and pamphlets. Thirty-five of us from six different states gathered at a most appropriate time of year for this training — early November, during what the Mexicans call Los Dias de Muertos or Days of the Dead, Mexico's traditional holiday honoring departed ancestors, friends and family. This is a time in the wheel of the year when the "veil between the worlds is thin," and it felt to be an auspicious time to further my training in Death Midwifery!

I remember the first time I became aware of the reality of death. The year was 1962; I was in second grade, and not more than seven years old. I would walk twelve blocks to my grade school, outside the city limits north of Spokane, WA, and I was often accompanied by my older sister, Cheri. During this walk I would always see a young girl, about my age, from a distance, walking with a nurse or a nanny. What first caught my eye was her size; she was unusually overweight for a girl her age. There was also something mysterious about her, for she lived in my neighborhood and yet I never saw her at school. She was never alone on these walks in that she always had an adult with her; and yet she was always alone, in that I never saw her with other children. I often thought about her, and wondered if she was lonely, but I was too timid a child to introduce myself and befriend her. I eventually discovered that she suffered from leukemia, and that the medicines she took caused her to gain the weight. I never knew her name, and only saw her on her walks, on my way to and from school.

One day I realized that I had not seen her walking for several days in a row. I don't recall how I found out, but word came that she had died. The finality of it began slowly sinking in and my innocent sense of well-being came crashing down around me. Death did not just come to old people! Someone my age could, and has died! Suddenly, I realized that it could also happen to me. I remember going to my mother in her bedroom, lying on her bed, sobbing, and trying to explain to her what was wrong, longing for consolation that I knew in my heart of hearts she could not give. This was a hurt she could not kiss away. The world shifted for me that day in an irrevocable way. I was crying, not only for the unnamed, unknown girl; but I was crying for the recognition that some day I, too, would be no more on this earth, and I was afraid.

That fear of death stayed with me throughout my childhood and into my middle adulthood, primarily because, like most of us in this culture I was not taught experientially about the natural cycles of life and was protected from any direct contact with human death. The first funeral I attended was for my paternal grandmother when I was 14. There was a closed casket, and I never got to see her before she was buried. Death was such a scary thing precisely because it was so mysterious and unknown to me, and I was so inexperienced with it. We humans tend to be afraid of things that we do not know, and therefore do not understand. The truth is that our culture teaches that death is something to be ignored, denied, feared, and avoided as much as possible. We try to insulate ourselves from the reality that death is a natural part of the cycle of life.

As a young adult I studied Native American and European earth-based spiritualities, and through the teachings of the Medicine Wheel came to know more intimately about the life-death-life cycle, ever present in the seasons of the year. In my mid-thirties I experienced a metaphorical death through the loss of a ten-year marriage that I valued. This shattering led me to explore many of the classic descent myths. The myths helped me, after much resistance, to befriend the surrender and letting go process that is inherent in any death, be it physical or metaphorical. Although it took me many years to heal from that experience, I did emerge with a stronger sense of Self and a belief and deeper understanding in the promise of renewal that follows any death. I eventually came to see the divorce as one of the most valuable experiences of my life. I was becoming more familiar with the territory of death. However, it was not until I was in my early forties that I had the privilege of being present at the death of a dear friend, Sara, in 1997 and my fear of death completely fell away.

Sara had been a participant in the first year of a women's spiritual growth group that I co-created and co-facilitated with my friend and business partner, Renie Hope, called Gaia Spirit Rising: Healing Ourselves, Healing the Earth. From the fall of 1989 to the spring of 1990, Sara, along with fifteen other women that year, gave herself fully to nine months of gathering weekly together in circle, exploring issues of spiritual, cultural and personal transformation through study, discussion, movement, creative expression, singing, drumming and sacred ceremony. Sara, like most of us, had grown up a daughter of the patriarchy, in a male-defined religious institution and identified fully with male-defined ways of being successful in the world. Like many women, Sara was searching for a "God who looked like her" and she used the Gaia curriculum and experience to find a new source of empowerment for the second half of her life. Sara especially loved the singing and drumming that I would lead at the beginning of each gathering. Renie and I went on to facilitate the Gaia program for seven more years, but there was something about that first group that bonded especially deeply. After the official end of the program, they continued meeting without us through the years, with Sara emerging as one of their strongest leaders.

Then, in the fall of 1993, Sara was diagnosed with cancer. Her doctors gave her only three to six months to live. Sara's one wish at that point was to live to see her grandchild. Her daughter was pregnant at the time of her diagnosis. Her Gaia group and the extended Gaia community rallied around her, supporting her and her husband, Allen, as best we could: hospital visits during her many surgeries, emotional support, healing ceremonies - creating ways to uphold Sara and to hold our own sense of shock and disbelief that this was happening to one of us, so young. Sara lived on, not only to see her granddaughter's birth, but also beating her doctors' timeline by three and a half years.

However, in the spring of 1997, I received a phone call from one of the Gaia women telling me that Sara was well into her dying process, and that if I wanted to come to Seattle and say goodbye to her, I should do it soon. I was also informed that Sara had requested that I facilitate her memorial service. When I arrived at Sara's home, she was surrounded by the sounds of life; her hospital bed was in her living room, a makeshift altar nearby, candle flickering, casting shadowed light on fresh spring flowers, pictures of her loved ones and her special, sacred objects. The exquisitely beautiful and lovingly hand-crafted quilt made by her women's group hung nearby, each square a testimony to Sara's bright and giving spirit, and how cherished she was by each woman. Her family was there in support of her process and to grant her last wish — to die at home.

At first the everyday atmosphere seemed to contradict what was happening. Sara's slow, labored, and uneven breath, was taking her step by invisible step closer to her passing; amidst a backdrop of her family chatting away over a supper brought in by Erin, one of Sara's closest friends, and also a Gaia 1 participant. There was an incongruency here, and yet a lovely perfection, for death is a part of life, as much as our culture tries to deny it. I was grateful to be included in this sacred leave-taking. However I was feeling awkward, as I had never been so close to human death before, and because there was so much in my heart for Sara, but no protected, private space to share it. I leaned over to whisper to Sara my assurance that I would be honored to facilitate her memorial service. I wanted her to know so she would have one less worry, yet as I spoke the words, I realized that although semi-conscious, she could no longer carry any concerns of this temporal, physical place. She was too far on her way. Still, she opened her eyes, silently communicating to me that she understood and knew that I was there.

I sat next to her, longing to help ease her transition. The thought of singing to Sara crossed my mind, but it was then edited out by the impracticality of doing so in an environment where it might not be understood. Within just a few minutes of thinking this, Sara's husband Allen comes to me and asks, "Would you be willing to sing some of the Gaia chants that Sara loves so much?" I was stunned, yet grateful for the synchronicity of the moment. Relieved to have an avenue of expression for the mixture of joy and pain, sorrow and love I felt for Sara all at once, I began to sing. Suddenly the words rang through with clarity and new meaning:

"Mother Earth, Birth and Death,

Come and hold me in your arms,

Mother Earth, Life and Breath,

Come and hold me in your arms.

Cradle me, Circle me, Hold me in your Mystery.

Challenge me, strengthen me, Hold me in your Heart..."

Chanting is an ancient method of the repetition of simple words and melodies, like a lullaby, repeated over and over again.

"We are opening up in sweet surrender to the luminous love light of the One..."

This took me deeply into a place of communication and communion with Sara that no amount of speaking to her could have. Her breathing quieted and her pain and agitation seemed to ease for a while.

"Return again, return again, return to the land of your soul..."

After an hour or so I stopped. It was time for me to go. Remarkably, the rest of Sara's family had retreated upstairs, and I was surrounded now only by the quiet of Sara's breathing.

I returned the next day as soon as my schedule allowed. I arrived to find that Sara had died only twenty minutes prior, and Ruthie, another of the Gaia 1 group and a registered nurse, was there alone. It was time to bathe Sara's body and to prepare for her lying-in-honor. We did this together in silence. Not only did I find my fear released through this experience, but I also felt incredibly gifted by it. It was heart opening, healing and transformational. When someone dies, the portal between the worlds opens, just as it does during a birth, and it is very powerful. I was transformed by being present to this energy, by touching and bathing this woman who had been my friend, but who was now in the process of leaving the shell that was her physical body. Rather than being afraid, I found it to be a privilege and an honor to be able to tend to someone who has passed. Her spirit permeated the room during those initial hours after her death, and slowly, over time diminished. Finally, I felt Sara's spirit dissolve into all of nature, into everything, including myself. And, I no longer feared death. This was Sara's gift to me, and, over time, after having dreams about caring for the dead and experiencing the deaths of three more friends, eventually brought me to my current sense of calling as a Death Midwife.

Conscious after-death care follows in the footsteps of home birthing, and conscious death and dying. Hospice has helped bring caring for the terminally ill back into the home with wonderful, loving care. However, once the person dies, most people call a funeral home. Strangers arrive; the deceased is zipped up into a body bag and immediately taken away. This can be a very impersonal, institutionalized process, and always includes embalming, which is expensive, not necessary and is actually very violent. Many faith traditions believe that it may take up to three days for the soul to leave the body. Is this how we would want our loved one's body to be treated during this important transition? How much more wonderful for them to be at home, ritually washed and dressed by those who love them. What a gift it is for those left behind to be able to spend time with the body of their loved one, to create and hold sacred space for the loved one to lie-in-honor, to have the time and privacy to do their grieving, and to perhaps transform their grief through the creative process of decorating the urn or casket, typically a pine or cardboard box.

Caring for our loved ones after death is nothing new. It has only been three or four generations since everyone cared for their own at home in this country. Consciously tending the dead at home is reclaiming something very ancient — something most cultures around the world still reverently do for their loved ones. It is only natural that we bring back this very personal, family involvement and participation in a way that becomes a simple, loving part of the cycle of our lives.

Little Known Facts:

- Caring for your own dead and creating a home funeral is completely legal in Washington, and in most states in the U.S.

- Embalming is not essential.

- A loved one can lie-in-honor in the home of family or friends. One to three days is customary.

- Friends and family can create an atmosphere that reflects cultural and personal beliefs, including casket decoration, ritual and storytelling.

- The average cost of a funeral in the U.S. is $8,000. A loving and meaningful ceremony can be created to honor someone's life for a very small cost.

A family member or Advanced Health Care Directive Agent can:

- act in lieu of a funeral director to facilitate all arrangements and carry out all decisions;

- fill out and file end-of-life documentation;

- transport the deceased in any vehicle to a home, place of ceremony, crematory, or cemetery.

Marilyn Strong holds a BA in Religion and Adult Education and an MA in Spirituality and Culture. She is a skilled creator and facilitator of adult spirituality programs and workshops. She also performs weddings as a non-denominational minister, is a vocalist and a Certified Death Midwife. She provides coaching and information on natural death care and services to families as a home funeral guide, including memorial services. For more information see her website at www.handsofalchemy.com or email her at lapis@whidbey.com.

Watch an exerpt of the video, Hands of Alchemy on YouTube

Return to Mythic Passages Menu

Subscribe to the Mythic Passages e-magazine

|