|

Tension: Exile, Evil, Sacrifice, Meaning, Gnosis

A conversation with Betty Sue Flowers, Richard Smoley, and Robert Walter, moderated by Bradd Shore

© 2004 Mythic Journeys

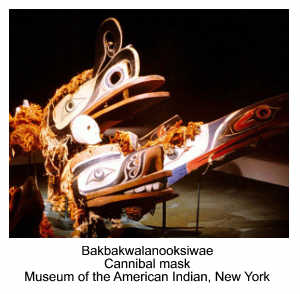

[Images: "Wagilag Sisters" by Philip Gudthaykudthay; Bakbakwalanooksiwae cannibal mask]

We are all visitors to this time, this place. We are just passing through.

Our purpose here is to observe, to learn, to grow, to love... and then we return home.

— Australian Aboriginal Proverb

Shore: I'm Bradd Shore, a professor of anthropology at Emory University, and the director of MARIAL (Myth and Ritual in American Life). I've been a very interested participant in the stages of the planning of this conference. Today we have three very interesting participants in what I hope will develop into an interesting and unpredictable conversation, which is the whole point of this. We have no idea where we are going. Most of us have not talked before or planned. The idea is that we've got some very interesting people.... I'm going to let our participants introduce themselves. Some of them are going to be known to you, if not everybody. What I'd like to have them do is talk a little bit about how they got interested in myth, and this whole topic, and what brings them here, and interests them in general. Then we'll plunge into the more specific topic. Betty Sue Flowers, do you want to start? Shore: I'm Bradd Shore, a professor of anthropology at Emory University, and the director of MARIAL (Myth and Ritual in American Life). I've been a very interested participant in the stages of the planning of this conference. Today we have three very interesting participants in what I hope will develop into an interesting and unpredictable conversation, which is the whole point of this. We have no idea where we are going. Most of us have not talked before or planned. The idea is that we've got some very interesting people.... I'm going to let our participants introduce themselves. Some of them are going to be known to you, if not everybody. What I'd like to have them do is talk a little bit about how they got interested in myth, and this whole topic, and what brings them here, and interests them in general. Then we'll plunge into the more specific topic. Betty Sue Flowers, do you want to start?

Flowers: All right. How I got interested in myth? Gosh, I got interested in myth as early as I can remember. I would see my mother and father responding differently to the same event, and I couldn't understand what reality was. You know how children try to understand reality by looking at their parents. And then I realized that, although the same thing had happened, my father told one story about what was going on, and my mother told another. At that point I became a scenario builder, which is one of the things I have done in relation to stories and myths with corporations and government entities — scenario work. I used to be an English professor at the University of Texas. Now I direct the Lyndon Baines Johnson Presidential Library, which is another whole mythological trip. (laughter) Also, I worked with Bill Moyers on Joseph Campbell and the Power of Myth and did the book, and was the series consultant on that project, which is where I first and last saw you (indicating Robert Walter). There's a lot more, but that's the thumbnail sketch. I should add that when I taught English it was with the emphasis on poetry. That's my academic field, poetry, and the kind of comparative mythology that doesn't arise out of anthropology, but out of poetry. Flowers: All right. How I got interested in myth? Gosh, I got interested in myth as early as I can remember. I would see my mother and father responding differently to the same event, and I couldn't understand what reality was. You know how children try to understand reality by looking at their parents. And then I realized that, although the same thing had happened, my father told one story about what was going on, and my mother told another. At that point I became a scenario builder, which is one of the things I have done in relation to stories and myths with corporations and government entities — scenario work. I used to be an English professor at the University of Texas. Now I direct the Lyndon Baines Johnson Presidential Library, which is another whole mythological trip. (laughter) Also, I worked with Bill Moyers on Joseph Campbell and the Power of Myth and did the book, and was the series consultant on that project, which is where I first and last saw you (indicating Robert Walter). There's a lot more, but that's the thumbnail sketch. I should add that when I taught English it was with the emphasis on poetry. That's my academic field, poetry, and the kind of comparative mythology that doesn't arise out of anthropology, but out of poetry.

Shore: Do you miss teaching?

Flowers: Very much. I miss academia, but teaching... I'm an adjunct professor of Pastoral Ministry, if you can imagine, at the Episcopal Seminary, so I still teach. And I teach in an honors program, so I'm still teaching. But I miss being a professor because that's a certain kind of teaching.

Shore: Sure. That's great. On my far left is Richard Smoley.

Smoley: I don't know when exactly I first became interested in myth. I had a great aunt who was a nun who, when I was ten years old, took me aside and told me that I was thinking too much about religion. (laughter) So I guess it goes fairly far back. I certainly became more interested in it in a spiritual quest, and drawn more powerfully to it when I was in my early twenties. When I was a student in England there was a Kabala group that met, a half dozen somewhat rag-tag people, but it was for me a start of my own spiritual search which I've followed in a rather meandering way since then. In terms of work I've done, for a number of years I was editor of a magazine called Gnosis, a journal of the Western spiritual traditions, which stopped publishing in 1999. I like to feel that we covered a lot of these topics and from a number of different perspectives without any sectarian orientation. I've written a couple of books. One is called Hidden Wisdom, which is a guide to Western traditions in general, and the second one is called Inner Christianity, which is a guide to the esoteric Christian tradition. In short these days I'm working mostly as an author and speaker. Smoley: I don't know when exactly I first became interested in myth. I had a great aunt who was a nun who, when I was ten years old, took me aside and told me that I was thinking too much about religion. (laughter) So I guess it goes fairly far back. I certainly became more interested in it in a spiritual quest, and drawn more powerfully to it when I was in my early twenties. When I was a student in England there was a Kabala group that met, a half dozen somewhat rag-tag people, but it was for me a start of my own spiritual search which I've followed in a rather meandering way since then. In terms of work I've done, for a number of years I was editor of a magazine called Gnosis, a journal of the Western spiritual traditions, which stopped publishing in 1999. I like to feel that we covered a lot of these topics and from a number of different perspectives without any sectarian orientation. I've written a couple of books. One is called Hidden Wisdom, which is a guide to Western traditions in general, and the second one is called Inner Christianity, which is a guide to the esoteric Christian tradition. In short these days I'm working mostly as an author and speaker.

Shore: And to my right is Robert Walter.

Walter: I guess that I first got interested in myth when I was a Jesuit novice and an insomniac. I discovered that I could sneak into the library at night. If I removed the red film from the exit, I got a shaft of light that went right down one row of books. I had an interest in the theater at that point, and I discovered that this was Comparative Religion. With my interest in theatre, I looked down this row and found Masks of God. This struck me as an interesting title, so I sat on the floor of the Jesuit Novitiate, read my way through four volumes, and then I left the Jesuits. (laughter) It wasn't causal, but it wasn't coincidental either. I subsequently then moved into theater, and was on the founding faculty of the California Institute of the Arts where my interest was in secular rituals. At that particular point, I crossed paths with Joseph Campbell, and ten years later started working with him as his editor. As his literary executor, I posthumously completed the Historical Atlas, and I have been the president and executive director of the Joseph Campbell Foundation ever since. Walter: I guess that I first got interested in myth when I was a Jesuit novice and an insomniac. I discovered that I could sneak into the library at night. If I removed the red film from the exit, I got a shaft of light that went right down one row of books. I had an interest in the theater at that point, and I discovered that this was Comparative Religion. With my interest in theatre, I looked down this row and found Masks of God. This struck me as an interesting title, so I sat on the floor of the Jesuit Novitiate, read my way through four volumes, and then I left the Jesuits. (laughter) It wasn't causal, but it wasn't coincidental either. I subsequently then moved into theater, and was on the founding faculty of the California Institute of the Arts where my interest was in secular rituals. At that particular point, I crossed paths with Joseph Campbell, and ten years later started working with him as his editor. As his literary executor, I posthumously completed the Historical Atlas, and I have been the president and executive director of the Joseph Campbell Foundation ever since.

Shore: As you can see, we've got a powerhouse of interesting folks here. Let's see what we can do with these topics. I want to try to begin by trying to frame the topic, and trying to talk very briefly to understand what it is that we're engaged with here. When we think of creation, I think that an ordinary, everyday discourse, the idea of creation is normally understood as a positive idea, particularly when it is connected with the idea of creativity or creator. We think of creation as a beginning, as a spark, the beginning point itself. It tends to be a concept that developed in what you might call a major key. The interesting thing is that a little reflection on creation traditions and on creation myths suggests that it's a lot more complicated than that. Creation is very frequently associated with its shadow side, with its addictive side; the idea is that creation is in tension with something destructive or something that appears to be the opposite of the simple notion of creation. What we're here to do is to think aloud about how this tension between the constructive and destructive side of creation plays out in the things that we know and the things that we're interested in. What can we take away, understand, and learn from this? I'm going to start by giving two quick examples of this in work that I've done, and I'm going to ask each of the panelists to think aloud about where in their own confrontations with myth are some very interesting examples of the dark side of creation. By the way, we're not going to talk only about world creation, but about the creative process itself, and what the connection would be. Is there a dark side to that as well?

I think of two traditions that I have written about that both illustrate in very different but powerful ways the shadow side or the tensions involved in creation. One is in a group that I spent a lot of time writing about is the Yolngu people of Northern Australia, the Australian aborigines. They have one of the most extraordinary creation stories that I know, and I've devoted a lot of ink to looking at it. It's called the Wagilag Sisters who created the world. Of course, as is common in aboriginal tradition, it is clear that they are simultaneously creating a world, and the world always was. There's this tension. They're creating something that nonetheless existed because the dreaming is not in time. It's something that is always there. So this is a dream time story about emergence. The kind of creation that the sisters did evolves — taking a world that is whole and separating it, which is very familiar in the Christian tradition — dividing it. There's a kind of creation in division. They divided the world by naming things, a tradition of logos, of giving things their names much as Adam did in the Christian tradition. They gave things their names. The interesting thing that the myth states is that as they named each creature, they killed it. What they're doing, of course, is emulating what men did — they killed it with a spear. As they killed it they said, "You will be sacred by and by." There's some process in this creative tradition which involves some combination of separating, of naming, and — in the process of destruction, of killing — that is central to it. I think of two traditions that I have written about that both illustrate in very different but powerful ways the shadow side or the tensions involved in creation. One is in a group that I spent a lot of time writing about is the Yolngu people of Northern Australia, the Australian aborigines. They have one of the most extraordinary creation stories that I know, and I've devoted a lot of ink to looking at it. It's called the Wagilag Sisters who created the world. Of course, as is common in aboriginal tradition, it is clear that they are simultaneously creating a world, and the world always was. There's this tension. They're creating something that nonetheless existed because the dreaming is not in time. It's something that is always there. So this is a dream time story about emergence. The kind of creation that the sisters did evolves — taking a world that is whole and separating it, which is very familiar in the Christian tradition — dividing it. There's a kind of creation in division. They divided the world by naming things, a tradition of logos, of giving things their names much as Adam did in the Christian tradition. They gave things their names. The interesting thing that the myth states is that as they named each creature, they killed it. What they're doing, of course, is emulating what men did — they killed it with a spear. As they killed it they said, "You will be sacred by and by." There's some process in this creative tradition which involves some combination of separating, of naming, and — in the process of destruction, of killing — that is central to it.

The second one is from a little closer to our own geographical shores, and that is from the traditions of the Northwest coast Indians, specifically the Kwakiutl from up around the Vancouver area. What I want to describe is not a particular myth, although this is embedded in a lot of myths, but to have you remember totem poles. These are the very famous, huge poles which the peoples of the Northwest coast brilliantly still produce today. Some of these poles are called cannibal poles. The great figure of their creation story in Kwakiutl is Bakbakwalanooksiwae, who is the cannibal at the north end of the world, the world destroyer who consumes the world through eating. They celebrate their winter ceremonial as a way to confront the eating of the world, and to transform it. The amazing thing about these cannibal poles which many of them carve is that, if you look carefully at them (and the American History Museum has a particularly beautiful example) they have images of animals coming out of the mouths of other animals. It's a chain in the pole. The interesting thing that they've produced here is a visual pun because this is simultaneously an image of world destruction through eating, and vomiting which is world creation. You can't tell, when you look at the poles, whether the animals are being destroyed or born through the mouth. The images are exactly balanced at the middle. That's where I want to take off. What I'd like to do is pass the torch to anybody who wants to start, and give us some other examples that come to mind, either in your writing or in things that you know about that indicate the same kind of balance point. The second one is from a little closer to our own geographical shores, and that is from the traditions of the Northwest coast Indians, specifically the Kwakiutl from up around the Vancouver area. What I want to describe is not a particular myth, although this is embedded in a lot of myths, but to have you remember totem poles. These are the very famous, huge poles which the peoples of the Northwest coast brilliantly still produce today. Some of these poles are called cannibal poles. The great figure of their creation story in Kwakiutl is Bakbakwalanooksiwae, who is the cannibal at the north end of the world, the world destroyer who consumes the world through eating. They celebrate their winter ceremonial as a way to confront the eating of the world, and to transform it. The amazing thing about these cannibal poles which many of them carve is that, if you look carefully at them (and the American History Museum has a particularly beautiful example) they have images of animals coming out of the mouths of other animals. It's a chain in the pole. The interesting thing that they've produced here is a visual pun because this is simultaneously an image of world destruction through eating, and vomiting which is world creation. You can't tell, when you look at the poles, whether the animals are being destroyed or born through the mouth. The images are exactly balanced at the middle. That's where I want to take off. What I'd like to do is pass the torch to anybody who wants to start, and give us some other examples that come to mind, either in your writing or in things that you know about that indicate the same kind of balance point.

Walter: I just want to pick up on a sort of underlying principle there, which is that arguably the myths exist to reconcile people to the terrible horror of existence where life lives on life, where life is being born by other life dying. You speak of the animals; you can carry that forward to the sacrifice metaphors where the plant has to be cut down for the seed to grow to be planted so there will be new seed. We can carry that all the way up to Richard's area, up to Western spirituality because, arguably, that's the Christian myth, too.

Smoley: One thing that underlies practically all myths I can think of is a notion that somehow something is wrong, or something is not as it ought to be. The Christian myth is only one version of that. It happens to be a very familiar one. I sometimes like to say that man is the animal that believes something is wrong. It seems to be, if not exclusive to us, certainly one distinctive characteristic of us as humans. Any of the myths I've heard today only bear that out. To take one example that I think you've all heard, in the Finnish myth. When the eggs are laid on the goddess's knee, she moves her knee, and the eggs roll off, there's a sense that somehow that shouldn't ought to have happened. (laughter) Similarly, the animal being killed as they're named — there's sometimes a felt sense of "What is this? Why is it like this?" As you were saying, "death by eating." I don't have a particular answer to why this is so, but I feel that it is something that is essential. It would be very difficult to construct a myth that doesn't have some element of that, where something doesn't go wrong, where something doesn't seem awry. We can bring the word evil into it if you like, but you don't' even need to. For me that's a very interesting thing. It sets up a certain dynamic. Some even say in the Western traditions that imperfection is the principal upon which everything is based. If it were perfect, it would be identical to what it came out of, and it has to be different, because otherwise it wouldn't exist as itself. In a sense, imperfection gives birth to everything. Maybe that's one aspect of it, since we feel it very deeply. People feel very deeply about politics, the political situation, no matter whichever side you're on, something's wrong. Its "them people" whomever "them people" happen to be. It's an interesting issue. It runs very deep in us.

Flowers: Four unrelated points, which probably are related, but I don't see a relationship yet. First, I think you kill anything by naming it because when you name something (which is why in many traditions you don't name the name of God) you fall under the illusion that you have it. That kind of hubris is typical of human beings, but every time you name something you kill it. That's our first act, to control. Creation stories often have naming aspects to them. This logos bit is a key part of creation, and part of its shadow.

Second: I think that this shadow part of creation often comes with time, that creation is the beginning of time. In Time, that great mystery which even theists don't know what to do with, has all kinds of weird stuff in it. What is it about Time and Death? Every time you start something — you say, "Time!" You get out of Eternity and get into something that is unique, specific, and has Death at the end.

Third point: Creation stories often have to do with One, Two, and Three; and then The Many. "In the beginning" is One; something undifferentiated. Somehow Two happens. What is the nature of Two? Mischief. Two can either fight or make love. By the time you get to Three, you have the mystery of the Trinity. Mystery enters the world. It's undifferentiated, the mischief, the mystery. Every creation story has undifferentiation, mischief, and mystery in it.

Shore: That's good. That's fascinating.

Flowers: Four: Part of being a mythologically oriented human being is to say, "Okay, where is the myth of creation presenting itself right now?" It's a little game you play with yourself. You've probably already noticed that the myth of creation is happening right here in that Osiris box over there. Did everyone see the Osiris box? Isn't that a box of grass? The dead Osiris in Egypt, you can see the Osiris boxes in the tombs. Osiris dies, and out of his body grows the grass. So, you just walked by a dead god when you came into this room. There's an Osiris box in this very room. Whenever, by synchronicity, you find a myth just manifesting, you declare to the mythologically oriented that it has something specifically to do with you in that moment. You make that declaration, and then you explore it. That's the mythological dimension that is always present — always present. My scientifically-minded friends say, "Oh, you're just making stuff up." That's because we're the story-telling animals. We're all made up. Somehow, in the beginning, was the word, and we got made up. Here we are continuing to create and make up.

Walter: Just before I came here, I opened up The Devil's Dictionary and looked up mythology. It says, "The stories we made up about gods and heroes before we made up what actually happened." (laughter) It is also saying, "It is this; it is not that!" So, once again, you get that tension. I'd like to toss out the idea that this duality is one of the fundamental perceptions of our existence, beginning with the sun goes down, the sun comes up. Light and dark. People are born, people die. We measure things between how high they are and low they are. Our experience is meted out between that. Somehow there is the creative tension. In trying to navigate that in some way, the rocking of the ship keeps me steady. You're making your way along there, trying to hold that tension and go on. That's life.

Shore: That's interesting. Let me see if I can tie together a couple of points, because this is just fascinating. There is a wonderful book by the psychologist, Jerome Bruner, called Acts of Meaning: Four Lectures on Mind and Culture (Jerusalem-Harvard Lectures) . In that book, Bruner argues that narrativity or story-telling is not just another kind of model of the world. The impulse to tell stories is intrinsically human, is hardwired. What's interesting is when he says that when people tell stories it's triggered by trouble. When things are going well, there's not the impulse. We often call it gossip. You're standing in the street and a building blows up. The first thing you do is try to protect yourself and run for help. Then you start to tell stories. The story-telling impulse itself is related to trouble. That would suggest that the impulse for creation stories is related to trouble. What is the trouble in creation? To my mind the trouble in creation is the possibility of not creation, that is death, or destruction. Therefore, the very idea of creation poses the opposite of its double, which then impels the telling of the story. It's not a surprise to me that the destruction side of it will always creep into the telling of creation. It's central to the impulse for telling a story. . In that book, Bruner argues that narrativity or story-telling is not just another kind of model of the world. The impulse to tell stories is intrinsically human, is hardwired. What's interesting is when he says that when people tell stories it's triggered by trouble. When things are going well, there's not the impulse. We often call it gossip. You're standing in the street and a building blows up. The first thing you do is try to protect yourself and run for help. Then you start to tell stories. The story-telling impulse itself is related to trouble. That would suggest that the impulse for creation stories is related to trouble. What is the trouble in creation? To my mind the trouble in creation is the possibility of not creation, that is death, or destruction. Therefore, the very idea of creation poses the opposite of its double, which then impels the telling of the story. It's not a surprise to me that the destruction side of it will always creep into the telling of creation. It's central to the impulse for telling a story.

Smoley: To go back to the point about naming and killing, Heiniger spoke to this quite well. He pointed out that logos in Greek comes from a root that means legos which means "to pick out". To name something is to pick it out from its background. Of course, the minute you do that, you're cutting it off from it's background. In a sense, there's a death implied in that.

Shore: How often we professors experience that. Our students experience that when you take a beautiful work of art and reanalyze it or explain it, separating it from its moment of performance or being. In that understanding of it, we trade something off. We lose something at the moment that we gain a kind of logos about it.

Walter: Even with the materials that go into making a work of art you are taking these materials, which were one thing, and destroying their existence in that realm. You can't get around it.

Flowers: I think that I disagree with Bruner a little bit, that stories arise out of trouble. I think that trouble arises out of stories. (laughter) I think stories come before trouble. We're such story-telling creatures. We even dream in stories. We are biological story-tellers. I noticed this because when I've observed gossip, there has to be trouble or be made up. If you've ever been a boss in a managerial situation, there's always trouble because, even if there is no trouble, somebody's going to talk trouble into being. We almost need trouble.

Smoley: Why do we need trouble?

Flowers: To make things happen. Otherwise we sit here in perfection and nothing happens. Every story has to have something happening. Whatever the balance is gets tipped, gets upset. Something happens.

Shore: As my Jewish grandmother would say, "Life is a tourist trap." (laughter)

Walter: I'm struck by the works of Samuel Beckett where he tries to pare everything away. He gets down to the final thing, and he's still got trouble. "Do I exist or don't I exist?" "It's me." "No, it's not I; it's somebody else." I was reading the work of a neurophysiologist whose name eludes me at the moment. He was being asked to report on what he had found in this brain surgery. He said, "For all the work we've done, we really know very little about the human brain, except the one thing: it is hard-wired for narrative."

Shore: That's it. That's very interesting. I'm an anthropologist who is unsure of this, so I asked Bruner about it; he's a good friend of mine. I said, "The canonical form of narrative in the work is that there's an opening, a setting of the scene, and then there's trouble of some kind. Then, inevitably, there's a move towards some kind of resolution. The resolution can be tragic or comic, but there's a closure. Once again, it circles back around. It does make sense to a lot of the traditional forms. It also makes sense in music in the sonata form or the form of music where we have development. There's a change to a minor key, and then there's a resolution back to the major key. I'm not sure if that form is universal or not; I suspect that it is not. That's not hard-wired.

Walter: Musicians will tell you that the music always exists, that they dipped down into the stream, and they picked it up, and they ride it. Then they come back up. Music never starts. Music never stops. It is a very different perspective that we've come to in the West.

Shore: It is true that in the West we tend to see evil as a separation. Then the story, whether it is in Paradise Lost or Paradise Regained, has this moment of separation or exile. Then it is recovery or renewal. I wonder is that the only way that Christian traditions have viewed the problem of Evil? We have this idea that Evil is diametrically opposed to Good. Then there's an attempt to overcome it and reunify.

Smoley: It's an interesting question. There's some kind of esoteric strain to the tradition, one of which is represented by the Church Father origin which teaches that the Devil is not God's enemy, but his servant. You see this in the Book of Job where the Devil goes up to pay a visit on God to tell him what's going on. He's more like a cosmic quality control officer or district attorney (laughter) rather than someone who is actually in opposition to God. He's here to test and prove us, but he's part of the whole thing. I think that the concept of the Devil as an enemy of God is a later one. Historians would trace it to the influence of Zoroastrianism, which is one of the world's more dualistic religions. What you say is largely true, there is a minority view that the Devil isn't quite as bad a fellow as we think. Smoley: It's an interesting question. There's some kind of esoteric strain to the tradition, one of which is represented by the Church Father origin which teaches that the Devil is not God's enemy, but his servant. You see this in the Book of Job where the Devil goes up to pay a visit on God to tell him what's going on. He's more like a cosmic quality control officer or district attorney (laughter) rather than someone who is actually in opposition to God. He's here to test and prove us, but he's part of the whole thing. I think that the concept of the Devil as an enemy of God is a later one. Historians would trace it to the influence of Zoroastrianism, which is one of the world's more dualistic religions. What you say is largely true, there is a minority view that the Devil isn't quite as bad a fellow as we think.

Shore: In many non-Western traditions, Good and Evil are not separated. They are a part of each other. What are some other examples of that.

Walter: Kali in the Eastern traditions. You gave the one in the Kwakiutl. In a lot of the primal societies, the Creator and the Destroyer are the same. We even see it sociologically. What's an acceptable behavior in one culture is totally unacceptable in another. In certain cultures, I would be offending you horribly if I show you the sole of my foot. Yet, in another culture, if I were to do this (makes some physical pose), my body language would be rejecting you. It's carried over in all of these unspoken judgments that we learn as we become a culture. The other great thing about the mythological perspective is that it allows you to step out of your own (perspective) and say, "What of this do I choose to embrace, and what of this has really gotten in the way of my ability to be a human life?"

Audience Member: You mentioned the idea of something taught in a lot of creation myths that is explaining something that really ought to be. An event happens that triggers something else. On the idea of exile and non-differentiation, the idea of thought seems to be something that plunges us into the tension of those things. The judgment for our part, from our experiences of quality, or our misperceptions involved in the sense of the experience; the tension comes from the "ought".

Smoley: I think that it goes back to the idea of "Resist Not Evil;" that if you dwell on it, you make it more real, you accentuate the tension. You'll notice that in an argument, if you insist on clinging to your point, it just gets worse and worse. If you say, "Yeah, I guess that you're sort of right...," sincerely or not, that disarms the tension. You're right; the "ought" is probably very much part of that whole problematic tension.

Audience Member: Another take on myth is that it is designed to get the reader or participant to realize first the non-differentiation or the illusion of (?), and second, the solution to the tension of people about "what I ought to do" or "what I ought not to do" (that) is found in the acceptance of that non-differentiation. I remember reading that Joseph Campbell asked the lead guru of the priesthood, "What about the suffering of the people in the world? How do I plumb that?" And the answer was suitably mystical and cryptic.

Walter: The anecdote is a little more telling than that. He said, "I understand you're saying that you accept all of this, but how can you say yes to war and suffering and pain and things." And his reply was, "For you and I, we must." Meaning that if you reach a certain point, you have three choices: say "Yes, it's great"; "No, I want to change it"; or "Well, it's sort of all right if I could mess around with these parts of it." When you're young, all of the myths and stories show you how to mess around and deal with it. As you get older, you see that the ones that endure have a transcendent quality. You start to see the message behind it. Pay no attention to the little man behind the curtain. He's not really there. (laughter) You're absolutely right that the classic Yin and Yang in Eastern tradition is that you couldn't have night without day; you couldn't have day without night. You can't have the black without the white. I think it leads to the resolution of those paradoxes because they are fundamentally unknowable. The myths start to address them.

Shore: In the Australian aboriginal tradition that I mentioned at the beginning, the idea of separation as an act of creation in death is interesting. That act of separation was viewed as the creation of what we would call the secular world, the visible world that we live in which requires distinction. In order to become knowable, those distinctions require that the things be cut off from their true connections to other things. What this is really about is not the creation of the world, but the creation of the knowability of the world. I'd call that epistemogenesis. That requires a kind of Death. What sacredness meant to the aborigines when they say, "You will be sacred by and by" is an eventual overcoming of the situation in a Hegelian sense. That kind of knowledge is given only to the old people, and it is connected with death and the loss of this world. There you get a much more complicated vision in which the act of dying is built into the act of creation in terms of regaining a lost sacredness. I find it a very interesting way to look at this, something a little different from what we're used to.

Audience Member: I was interested in your comments on destruction coming before creation, transformation leading to the death of what's seen before, and then the birth of what is to come. It is hard for individuals in the West to see transformation as anything other than death. Joseph Campbell talked about this in terms of death looking like a monster, like Frankenstein, because we only see the death aspect of it. I wanted to ask you folks your opinions on how we in the West observe transformation in terms of destruction?

Walter: Let me try one take on that. It's interesting. If we lift that transformation out of the animal world and put it in a metaphor that is perhaps less threatening, we make a value judgment of the full teacup. We say that a full cup is better than an empty cup, and yet if you want something to come into your life, you have to empty out your full cup in order to fill it up again. That's the same transformation removed from us as humans. You have to have an emptying out in order for something to come in. That's a concept that's very common in large parts of the world. Again, go to the Kwakiutl. When they want to be blessed they potlatch. They give everything away. "I'm having a wedding celebration. Come to my house. I give you everything. I know that when I give it all away, next time around it will all come back." It's a very different look at how we do those things. I think this goes back to that earlier tension we were talking about where we have avoidance of death and the ending, putting things in Time, just to be there. The Western tradition has this idea that the kingdom is "out there" as opposed to the Thomas gospel that the kingdom is spread in front of you and men do not see it. What do you do to make Time stand still? When you're in that space, there isn't any difference. To get in that space, you've got to pull yourself out of the mundane, what we call the day-to-day. That's scary. Walter: Let me try one take on that. It's interesting. If we lift that transformation out of the animal world and put it in a metaphor that is perhaps less threatening, we make a value judgment of the full teacup. We say that a full cup is better than an empty cup, and yet if you want something to come into your life, you have to empty out your full cup in order to fill it up again. That's the same transformation removed from us as humans. You have to have an emptying out in order for something to come in. That's a concept that's very common in large parts of the world. Again, go to the Kwakiutl. When they want to be blessed they potlatch. They give everything away. "I'm having a wedding celebration. Come to my house. I give you everything. I know that when I give it all away, next time around it will all come back." It's a very different look at how we do those things. I think this goes back to that earlier tension we were talking about where we have avoidance of death and the ending, putting things in Time, just to be there. The Western tradition has this idea that the kingdom is "out there" as opposed to the Thomas gospel that the kingdom is spread in front of you and men do not see it. What do you do to make Time stand still? When you're in that space, there isn't any difference. To get in that space, you've got to pull yourself out of the mundane, what we call the day-to-day. That's scary.

Flowers: Alchemy has the same trope, which is that you have to separate and purify the difference in the elements before you can put them together.

Shore: So this is basically what I would call the dialectical view of Destruction and Creation in which an act of death or separation is simply part of a journey or a process of transformation that's not linear.

Audience Member: I want to make a comment and ask a question. The comment goes back to the concept of Evil as the "separation from." I think that you just can't leave it there. You have to say, "Well, here is the whole Christian concept of the Fall. It's not just a separation, but a justification of epistemogenesis. I like that. If we premise that the birth of knowing is the basis of one's humanity, of the rational being, then my mind goes, "We're going to Descartes," that the center of humanity is that knowing is knowing. That's very exciting to me. I'd like your thoughts on this.

Shore: I thought about this starting with the aboriginal tradition, and then I thought it about in relation to Christian tradition, which actually has some real parallels. In the aboriginal tradition, what you get is very interesting. You get a telling of the myth of creation in which I've analyzed the narrative structure for myth very closely. Simultaneously, the (proposed) journey of where these two sisters went (on a map) goes from inside to outside. They frame it as an actual linear journey that is going somewhere. If you map the journey on a map of Australia, they are actually going in a circle. In a sense, they never have left where they were. They are telling you two stories at the same time. I call it a holographic style of story-telling where you get two images that are superimposed. One is an image of a linear journey from something to something else. The other one is a journey that is not a journey, but that always was. I said to myself, "What kind of creation genuinely has a development in it, but has no development in it?" This is the Dreaming. It's not the physical creation of the world, but the emergence of a child's knowledge of the world. It appears at first to be that the world is developing, but it turns out that it is really the child's understanding of the world that always was developing.

This whole myth really underwrites the age grading rituals of the mind of the Yolngu people who use this myth as a model for the socialization of their children, specifically the males in this society. So epistemogenesis is really what most people think of as these creation stories, then take omission in that they literally turn out not to be really about creation, but specifically about knowledge creation. You get something similar in all myths that deal with language as the source of creation. God said, "Let there be light!" and there was. What kind of creations involve speaking? We can't speak things into being; it's not an activation. But we can speak knowledge into being. Almost every myth that deals with words and naming as a source of creation is in some way about epistemogenesis. It's a central issue. It's very interesting to use this as a perspective to look at the world's creation myths and ask how many of them are really about world creation rather than about knowledge creation.

Walter: Not just the creation myths. Joseph Campbell used to do this gesture, and he'd say, "All the great myths are like this. There's something going on in here like this. You're looking at this part of it, but what you're really getting is the other part. Gertrud Mueller Nelson who, in 1991 at this conference in Georgetown called The Joseph Campbell Phenomenon: Its Implications for the Contemporary Church, told this story about how when her daughter Veronica was six, she was interviewed by a psychiatrist to see if she was mentally developed enough to go to kindergarten. The psychologist said, "Anika, do your parents read to you?" And she said, "My parents tell me stories." And he said, "Well, what kinds of stories?" And she said, "My daddy tells me Piggly Wiggly stories, and my mama tells me Greek myths." The psychologist says, "Myths, huh? Really?" And she says, "Uh huh, you know — mythology." And he says, "Yes, but can you tell me what a myth is?" And she said, "A myth is a story that's not true on the outside, but is true on the inside." And I was immediately brought back to that gesture of Joe's.

Shore: Myth is hard to define, but I actually had to do it when I wrote my grant for the Sloan Foundation to set up the MARIAL center for Myth and Ritual in American Life. What is myth? We're not supposed to have any. It turns out that we do. (laughter) Thank God for my grant. (laughter) I defined myth as a very significant framing of the true in something which is recognized as not true. What makes myth distinctive is that juxtaposition of true and not true. I said that there are two different kinds of myths from that point of view. One is what you might call the Classic Myths. These are the myths that most of this conference is dealing with. These are really human truths clothed in local fictions. Not everybody acknowledges that they are fictions, but many of us, when you do comparative work say, "Some part of this is made up." We wouldn't be interested in it if that central part, when there's something that was true that was inside there... somehow the fictional part of it allows us to entertain the central part. It gives us an entrée. I don't know why and I don't want to talk about that...

Flowers: I think that it's important to talk about that, because of that relation of Good to Evil. Goethe has Mephistopheles in his play Faust Flowers: I think that it's important to talk about that, because of that relation of Good to Evil. Goethe has Mephistopheles in his play Faust saying, "I am the spirit always intending evil but that works to the good." I think that if you didn't have a fictional shell to the true kernel, like science, we'd be throwing out these knowledges all the time; throwing them because we couldn't live with them long enough. Knowledge falls by the wayside, but fiction lasts. You can go back to fiction because it stays with you, and then you can see it unfolding. Seeing that unfolding of something that you live with a long time teaches you something beyond what is being unfolded. saying, "I am the spirit always intending evil but that works to the good." I think that if you didn't have a fictional shell to the true kernel, like science, we'd be throwing out these knowledges all the time; throwing them because we couldn't live with them long enough. Knowledge falls by the wayside, but fiction lasts. You can go back to fiction because it stays with you, and then you can see it unfolding. Seeing that unfolding of something that you live with a long time teaches you something beyond what is being unfolded.

Shore: So we're coming back to the kind of understanding you had when you were a child, but at a higher level.

Smoley: I find it interesting the meaning of the name "Homer", as in the poet of The Iliad and The Odyssey, as well as Simpson (laughter) is "hostage". In those days, they would exchange hostages, often live in the court of another king, with their own wives to make sure that everybody behaved themselves. And a hostage is, of course, by definition in exile. Whether (Homer) really was or not, we don't really know, but it's a funny name to have if you're not one.

Shore: And I think that it is also very suggestive as Robert said that artists, at least in the West, feel the necessity for self exile in order to create — exile either physically or socially, to be apart or separate. Let's turn to the second topic. We've kind of discussed it.

Walter: Evil or Exile. Let's stick with that story. What got Adam and Eve exiled from the Garden? Eating from the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil. Without the Evil, they're still in Paradise; without the recognition that there's two sides to this. Suddenly now they can differentiate between opposites, so that primal whole, that one is now two. Walter: Evil or Exile. Let's stick with that story. What got Adam and Eve exiled from the Garden? Eating from the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil. Without the Evil, they're still in Paradise; without the recognition that there's two sides to this. Suddenly now they can differentiate between opposites, so that primal whole, that one is now two.

Shore: In a sense, and in Bruner's sense, trouble is the source of self-consciousness.

Walter: Yes.

Shore: Any other thoughts about Evil?

Smoley: I feel the need to put in some kind of word on behalf of the God of the Old Testament. (laughter) He does get thoroughly bad press from Jehovah and many of his disciples. He's often regarded as a somewhat petulant, cantankerous, irritable figure, and no doubt that's true to some degree, but there's a verse in Isaiah that says, "I form the light and create darkness. I make peace and create evil. I, the Lord, do all these things." So far from representing a primitive notion of deity, I think it represents a very advanced one. That is to say, it shows that Good and Evil both come out of the primordial one, which is beyond morality and goodness, liking, not liking as we know it. I think that's very profound.

Shore: So that convention, modern Christianity is a kind of step down from that in a sense because it makes them dualistic? That's really an interesting thought.

Audience Member: I have never bought into the theory that Adam and Eve were banished because they tried to be gods. I think it's more than that.

Smoley: Well, it's not really quite what he's saying. He says, "Ye shall be as gods."

Shore: Actually, in the Psalms and quoted in the New Testament it says, "Ye are gods". It's not trying to be god, it's trying to make some fictitious dummy god out of yourself, which I suppose one could associate with the ego in a slap-dash way.

Flowers: Or you could have a more radical interpretation that God can't enjoy Paradise. If you become as God, you are not longer in Paradise, because the suffering of the world is apparent to God. As soon as you participate in suffering in the world, unlike children who are oblivious. As soon as you enter the world where there is suffering, you're banished from Paradise. God creates Paradise, but he himself can't dwell there.

Shore: This is like the archaic generation gap, which is inevitable — being with the kids who want to know for themselves and not be dependent. And so they are banished. The interesting thing about it is that all of our life is generated from that — that moment — which is considered the moment of Original Sin.

Walter: The Fall. Imagine our understanding of who we were if we, just for a minute, set aside the idea that there was a Fall. If there's no Fall, then there's no need for redemption...

Shore: There's also not a lot of fun. (laughter) In Paradise Lost Milton says, "The first moment of irony, of delicious irony, was born at The Fall." Adam eats of the apple and says, "Oh, thou most virtuous fruit!" in which the two meanings of virtue (formerly united and in harmony, and not very interesting) being "strength" and "goodness," split off. What's interesting is with that is born poetry. Milton knows that and tempts us to enjoy the fall and to enjoy Satan, because we live in an infralapsarian world. We live in a fallen world. We're made for that world in a sense, and we strive for something else. Without it we really wouldn't be who we are. Milton says, "The first moment of irony, of delicious irony, was born at The Fall." Adam eats of the apple and says, "Oh, thou most virtuous fruit!" in which the two meanings of virtue (formerly united and in harmony, and not very interesting) being "strength" and "goodness," split off. What's interesting is with that is born poetry. Milton knows that and tempts us to enjoy the fall and to enjoy Satan, because we live in an infralapsarian world. We live in a fallen world. We're made for that world in a sense, and we strive for something else. Without it we really wouldn't be who we are.

Walter: We step out of eternity and step into time, as Betty says.

Shore: That's right.

Audience Member: I'm thinking now of a book called Up from Eden: A Transpersonal View of Human Evolution that is based in part on Eugene Dexter's work in the idea that we were enmeshed in godhood, an unconscious enmeshment. You can't know something until you experience it. You have to separate from it to know and to grow back up to it. Someone else said that we come back to where we started, but with an awareness that we didn't have as children... that is based in part on Eugene Dexter's work in the idea that we were enmeshed in godhood, an unconscious enmeshment. You can't know something until you experience it. You have to separate from it to know and to grow back up to it. Someone else said that we come back to where we started, but with an awareness that we didn't have as children...

Flowers: And know it for the first time. In our end is our beginning.

Walter: Yes.

Flowers: The end of all our journeys is to return, to know it for the first time...

Audience Member: Where before we were it.

Shore: That's, in a sense, the difference between being smart and being wise. I remember I had a wonderful colleague at Sarah Lawrence when I taught there named Irving Goldman, who died recently. Irving was just a great inspiration for me. I remember that I used to go in, not long out of Graduate School, and we would talk. I would go on, and I'd be drawing diagrams on the blackboard of things I had discovered, and he would sit there and just say, "Oh yeah." The thing about Irving was that he no longer felt the need to lay it all out, but you knew from the way he talked that he had gone back to a different state. It was not the state of laying everything out. It was a higher and also lower state at the same time; a state in which he understood things and felt no need to lay it out or to say it. I'm still struggling for that. (laughter) I don't think I'm anywhere near that, but I think of Irving when I think of what I want to do. We have one more topic. I know... our time... I'm responsible for getting us through this in good time. Sacrifice is the third of our terms; sacrifice somehow being essential to birth and to creation. Any thoughts on the idea of sacrifice — essential, of course, to Christianity?

Walter: Essential to all of the planting myths, and, in a sense, to the early hunting myths. The animal has to be sacrificed in order for us to live. That carries all the way up into the early Pagan traditions that the Old Testament relates to.

Shore: Sacrificing is actually always presenting something as food.

Walter: Correct.

Shore: So it really means that it is being consumed but it is also regenerating something else.

Walter: We heard in the planting culture where the plant has to be sacrificed in order to create the seed, in the later embodiment, the king has to be sacrificed in order to fuel the land. There is this central idea that comes all the way up. I think it forms the Christian tradition. I think it was probably picked up in early Christianity from existing Pagan beliefs that were around there. There is that idea that the revelation of Paul on the road to Damascus was suddenly seeing Christ and seeing the Pagan gods as representing the same tradition. It, arguably, is part of what spread Christianity. I just think that it's underneath it.

Audience Member: (Question -- far away from the mic -- about the dozen white bulls that are sacrificed in the Minerva cult.)

Smoley: Because, in those days in traditional cultures, blood was regarded as the vehicle on which the life force rode. If you remember in The Odyssey, Odysseus wants to go to the Underworld so he kills any number of said creatures and all these shades come gibbering around this pool of blood wanting to feed on it. They get their food from this. That's the legend, at any rate, whether one wants to agree with it or not.

Audience Member: Somebody in this book slips on the entrails...

Shore: The bloodiness is what you're getting at. That's very interesting, because there are two components to sacrifice. One is horrible, physical destruction. Not hiding it or pretending that it doesn't exist, but confronting it with your eyes. It is there. A lot of mythical traditions are very different from modern American life where the physical quality of suffering or death is masked from people. Here it's addressed, but the term for the sacred season of the Kwakiutl, who I've mentioned a couple of times, meant "simulation" or "fraud". What that means is very interesting; sacrifice is simultaneously confronting the destruction of death, but because we are doing it as a ritual, we are controlling it at the same time. The other image is (that this) is under human control. What you do simultaneously is confront death in order to eat it. The Kwakiutl actually embody in their rituals the famous line of John Donne, "Death, be not proud" which ends "Death, thou shalt die." Death will die not by avoiding it but by ritually confronting it and controlling it at the same time. It simultaneously acknowledges it, but on the other hand, it suggests that human beings can somehow do something with it.

Walter: Death is the great teacher, too. Campbell talks about the fact that mythology arises, in his perception, with the recognition of death and the awakening of awe. Suddenly you're confronted with this thing that was alive and is not alive anymore. What does that mean? That's the unknowable. What's beyond that? Where has it gone? A lot of the earliest teachings come along to reconcile the human experience of death. The Inu raise a bear cub as the honored guest in the house. Then they slay the bear cub and feed it a bowl of its own meat stew. They send it back to the spirit realm so that the bears will come. The Bushmen identify with the animal, slay the animal, and send the animal back to the Other World to say, "Come to us as animals because we need you in order to live."

Shore: They're also saying, "You need us."

Walter: Yes.

Shore: That the regeneration of the species lies in the act of destruction.

Smoley: Precisely.

Flowers: I think that we have a lot of slaughter these days, but not much true sacrifice. Back to your point about being hidden, sacrifice requires the witness. Sacrifice has three actors in it. One is the victim, second is the witness (who sometimes actually performs it), and God. Without that triangulation of the three, you're not in the heart of a mystery. You're just slaughtering. "Sacred" and "sacrifice" come from the same root. When we read these stories, the slaughter is very apparent to us. The sacrifice part of it, the sacred disapears.

Shore: And the final one is meaning.

Flowers: You left two minutes for meaning? (laughter)

Shore: Maybe we'll change it to information. (laughter) Presumably, the question has to do with the shadow side of meaning — no pain, no gain — that meaning itself seems to traffic not only with enlightenment but with darkness as well.

Smoley: One thing that occurs to me in terms of meaning, you could say that when people perceive a meaningless world, it's because we're not doing our jobs. Our purpose for existence is to create meaning. Perhaps that's the need we supply in the biosphere, because no other creature seems to do it quite the way we do. That seems to be an integral part of what we're here to do.

Walter: And yet, to quote Campbell, people say they're looking for the meaning of life when they're actually looking for the experience of being alive...

Flowers: The experience of the rapture of being alive. You have to put that in there for Campbell.

Walter: ...and when you're caught in that rapture, meaning disappears. Meaning is an abstract concept. You're in it. You're riding the rapids. You're not understanding the nature of hydrodynamics. To some extent, in the search for meaning is the tension and the abstraction from the experience itself, which brings us right back around to this paradox of gnosis, of knowledge.

Shore: From a knowledge point of view, I always think of meaning like thinking of Plato's Meno. The interesting point there was that Plato concluded after interrogating this young lad about mathematics that he already knew the answers to everything he'd said, that "all knowing" is a form of recollection, anamnesis. It's clear that you really can learn new things, but new things are not meaningful unless they're apprehended as a form of memory, that you always knew them. In other words, from there you get the idea that knowledge is impelled by a sense of separation. Things only become meaningful when you say, "Wait a minute. I'm recovering them." There's a wholeness underlying the initial separation. That's the difference between somebody memorizing an answer to something, and somebody saying "Oh, my god!" The "oh, my god!" is experiencing this as if I always knew it.

Audience Member: I think that Robert Heinlein came up with the right word to describe that feeling. He said that it is "to grok."

Shore: To grok. (laughter) That's great. We're coming to an end, so I'll be able to answer my cell phone... (laughter)

Walter: What comes to mind quickly, to bring us back to our subject in a sense, there's this scene in a book called The Man Who Fell In Love With The Moon . This Native American has gone out on a vision quest, and he's standing out on a rock. He says, "Standing out on a rock, looking out, I understood it all. Life is a dream. It's all a dream when it's not in front of your eyes. What's in front of your eyes now will soon be a dream." That's why we have the stories. The stories put us in a place, allow us to remember, and allow us to keep on knowing. It's not until we know it again, until we find the narrative encapsulation, until we embody it, that we know it. Otherwise it's a dream. We're all going to walk out of here, and you're all going to be a dream. . This Native American has gone out on a vision quest, and he's standing out on a rock. He says, "Standing out on a rock, looking out, I understood it all. Life is a dream. It's all a dream when it's not in front of your eyes. What's in front of your eyes now will soon be a dream." That's why we have the stories. The stories put us in a place, allow us to remember, and allow us to keep on knowing. It's not until we know it again, until we find the narrative encapsulation, until we embody it, that we know it. Otherwise it's a dream. We're all going to walk out of here, and you're all going to be a dream.

Shore: And then like my friend Irving, you don't have to say it. (laughter) So silence. You've heard a lot of statements and a lot of collective learning and thoughtfulness. I would like to end this very interesting panel on a question mark. I'd like people to think about when all is said and done about creation, what mystery for you is still the deepest in terms of perplexity, questions? I prefer to end it on a subjective note rather than on an assertive note.

Flowers: Questions about creation, or just questions?

Shore: No, no, no... about any of the stuff that we've focused on today. What continues to really puzzle you?

Smoley: Why does it always seem so hard sometimes?

Walter: I guess that mine would be why is it that the more we know, the more we realize there is, and the less we realize we know? It's the onion sequence. How many layers to this onion? And when you finally get to the middle, what's there?

Shore: I always feel why am I impelled to always sound as if I'm saying something new when I'm really saying what I've already known? (laughter) And I say it again and again. And why is it that when I hear it, it sounds new to me? (laughter)

Flowers: I guess that the question arises, and I have a different question every hour, so that is just the question right now — is God enjoying it, too? (laughter)

Smoley: Thank you very much everybody. (applause)

Works Cited:

- Bierce, Ambrose, The Unabridged Devil's Dictionary

, University of Georgia Press; New Edition (January 3, 2002) , University of Georgia Press; New Edition (January 3, 2002)

- Boyce, MaryZoroastrians: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices (Library of Religious Beliefs and Practices)

, Routledge; 2 edition (February 5, 2001) , Routledge; 2 edition (February 5, 2001)

- Bruner, Jerome, Acts of Meaning: Four Lectures on Mind and Culture (Jerusalem-Harvard Lectures)

, Harvard University Press (September 1, 1992) , Harvard University Press (September 1, 1992)

- Goethe, Johan Wolfgang von, Faust: A Tragedy

, W. W. Norton & Company; 2 edition (September 2000) , W. W. Norton & Company; 2 edition (September 2000)

- Milton, John, Paradise Lost

, Oxford University Press, USA (August 19, 2005) , Oxford University Press, USA (August 19, 2005)

- Spanbauer, Tom, The Man Who Fell In Love With The Moon

, Harper Perennial (September 9, 1992) , Harper Perennial (September 9, 1992)

- Wilber, Ken, Up from Eden: A Transpersonal View of Human Evolution

Return to Passages Menu

Subscribe to the Passages e-zine

|