|

Introduction to Introduction to

The Art of Pilgrimage:

The Seeker's Guide to Making Travel Sacred

by Phil Cousineau, used by permission

Travel without sacrifice is tourism. — Phil Cousineau

I have been on the road all my life. When I was only two weeks old, my parents bundled me into their 1949 Hudson and drove thirty straight hours from the army hospital where I was born, at Fort Jackson in Columbia, South Carolina, to Detroit, where I grew up. That early journey set the peripatetic pace for my wanderings.

As a family, we took trips whenever possible. My father was convinced that travel was good for the mind, while my mother believed it was good for the soul. Our adventures were wide-ranging, from nostalgic visits to the ancestral family farm in northern Ontario to weekend drives to faraway museums, homes of inventors, and tombs of famous authors. of_fame.jpg) They were great getaways, but the trip that stands out for me was one my father planned especially for my benefit, to the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York. That visit to my pantheon of heroes was as powerful as later journeys to Delphi, Ephesus, or Jerusalem. It was a waking dream to walk on the hallowed ground where, according to legend, my favorite game was first played. I was awestruck at the chance to see the great relics of baseball: Babe Ruth's bat, Ty Cobb's spikes, and Shoeless Joe Jackson's glove. They were great getaways, but the trip that stands out for me was one my father planned especially for my benefit, to the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York. That visit to my pantheon of heroes was as powerful as later journeys to Delphi, Ephesus, or Jerusalem. It was a waking dream to walk on the hallowed ground where, according to legend, my favorite game was first played. I was awestruck at the chance to see the great relics of baseball: Babe Ruth's bat, Ty Cobb's spikes, and Shoeless Joe Jackson's glove.

After graduating from university in 1974, I undertook the rite of passage for thousands of my generation by recreating the old Grand Tour of Europe. Tramping over the cobblestones and riding the rails of the Old World for six glorious months lit a fire in my soul. I became so enthralled with the marvels of ancient history that I sent a telegram to my family explaining that I wouldn't be coming home for a long while. I told them that I had never felt so alive, and wanted to try to live somewhere for a stretch before going back and embarking on a career. In truth, I dreaded the idea of returning home.

I found a small room in a boarding house in Kilburn, in the north of London, and worked at an array of odd jobs for six months until I'd saved enough to start all over. To paraphrase Henry David Thoreau, I longed to travel deliberately to encounter the "essential things" of history, venture somewhere strange and unknown, ancient and elemental.

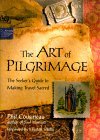

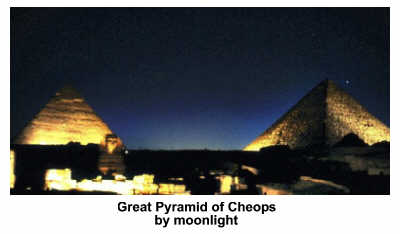

One day, I passed a travel poster for Egypt in the window of an airline office near Marble Arch, and my pulse raced with the thrill of recognition. I had fantasized about exploring the world of the pharoahs since childhood. I felt beckoned. One day, I passed a travel poster for Egypt in the window of an airline office near Marble Arch, and my pulse raced with the thrill of recognition. I had fantasized about exploring the world of the pharoahs since childhood. I felt beckoned.

Overwhelmed by the immensity of the ancient history looming before me, I prepared assiduously, seeking out the old Egyptology rooms at the British Museum, and reading arcane books on archaeology and mythology discovered in musty old bookstores along Charing Cross Road.

But as the day of my departure for Cairo loomed closer, I was overwhelmed with anxiety. The night before I was to leave, Ahmet, a young Egyptian who was also living in the boardinghouse, approached to wish me well on my journey. He asked me why I had chosen to travel to his homeland, what purpose I had. Taken aback, I paused for a moment, then told him I'd seen an exhibition, "The Art of Egypt's Sun Kings," at the Detroit Institute of Arts when I was in college, and it had haunted me ever since. Now I wanted to see with my own eyes "where it all began," meaning civilization itself.  Suddenly, I recalled something else, a photograph from the exhibition that burrowed into my memory, a black and white image of the archeologist Howard Carter taken at the moment he opened the tomb of Tutankhamen in 1923. In that picture, which I still have hanging on my writing room wall, Carter's expression isn't one of greed at the sight of gold artifacts, but radiance from the revelation of a sacred mystery. Instantaneously, I knew what I was seeking: not just a surfeit of impressions, the casualty of modern travel, but a glimpse of an ancient mystery. Suddenly, I recalled something else, a photograph from the exhibition that burrowed into my memory, a black and white image of the archeologist Howard Carter taken at the moment he opened the tomb of Tutankhamen in 1923. In that picture, which I still have hanging on my writing room wall, Carter's expression isn't one of greed at the sight of gold artifacts, but radiance from the revelation of a sacred mystery. Instantaneously, I knew what I was seeking: not just a surfeit of impressions, the casualty of modern travel, but a glimpse of an ancient mystery.

Ahmet nodded, gracefully, then extracted a small piece of cardboard from his pack of Gauloise cigarettes. On it he wrote some words in Arabic script which looke like birds in flight:

Be Safe and Well

Peace, Love, Courage

"This is the traditional farewell among my people for those leaving on a pilgrimage," he explained. At first, I was startled by his description of my upcoming trip. The word pilgrimage sounded arcane, even pious, suggesting a long-forgotten lesson from catechism class. Strange to say, as he spoke about his favorite archaeological sites along the Nile, the reverence with which he used the term enabled it to hover in my imagination. I remember him saying that making a pilgrimage was a way to prove your faith and find answers to your deepest questions. That stymied me; it forced me to ask myself what I believed in so strongly. But as Ahmet wrote down some names of friends and remote archaeological sites that would give me a sense of "the soul of the land," I realized that the word pilgrim captured what I had been secretly hoping to accomplish with my travels.

As we stood there in the dark hallway, I could smell tea brewing downstairs and hear the sound of trains rumbling from the nearby Tube station. Slowly, the thread of connection appeared between my boyhood journeys with my family and my recent wanderings to sacred sites such as Chartres Cathedral, the megalithic stones of Cornwall, the home where James Joyce was born, the healing waters of Lourdes, and the trenches of Flanders where millions died in the slaughter of World War I. My parents had instilled in me an appreciation for the soulful things in life — the world's sublime mysteries — and the fascination still burned in me.

Over the next few weeks, as I climbed the Cheops pyramid at midnight, explored the thrilling chaos of monumental sculpture in the Cairo museums, and sailed down the Nile in an azure blue felucca, Ahmet's words came back to me again and again. One afternoon, after exploring the tombs in the Valley of the Kings across the river from the vast ruins at Karnak, I wandered for hours in the desert sands nearby, a white bandana wrapped around my head to protect me from the fiery sun. Alone, I stumbled through the tumbledown ruins of unnamed temples until I came upon a group of Bedouins sitting in the shade of towering date trees. With supreme grace, they invited me to sit with them. They poured the finest mint tea I ever hope to drink. Patiently, they pointed out hieroglyphics on the fallen columns and examined the symbols for heart, eye, and the soul. The oldest among them slipped a wrinkled photograph out of his djellaba for me to see. He pointed at a young man laboring on an archaeological dig, then back at himself and at the rubble all around us. He was letting me know that many years before he had participated in the excavations of the temple grounds. A smile spread across his swarthy face as he made digging gestures with his hands. The gentle choreography animated the pages of the schoolbooks that still hovered in my imagination, and brought back my father's discussions about the ancient travelers here, Herodotus and Pausanius. The old truism rings true about the thrill of history coming alive, but there was more. a group of Bedouins sitting in the shade of towering date trees. With supreme grace, they invited me to sit with them. They poured the finest mint tea I ever hope to drink. Patiently, they pointed out hieroglyphics on the fallen columns and examined the symbols for heart, eye, and the soul. The oldest among them slipped a wrinkled photograph out of his djellaba for me to see. He pointed at a young man laboring on an archaeological dig, then back at himself and at the rubble all around us. He was letting me know that many years before he had participated in the excavations of the temple grounds. A smile spread across his swarthy face as he made digging gestures with his hands. The gentle choreography animated the pages of the schoolbooks that still hovered in my imagination, and brought back my father's discussions about the ancient travelers here, Herodotus and Pausanius. The old truism rings true about the thrill of history coming alive, but there was more.

Something ancient and holy was unfolding all around me. It was what the wandering pilgrim-poet Basho called "a glimpse of the underglimmer," an experience of the deeply real that lurks everywhere beneath centuries of stereotypes and false images that prevent us from truly seeing other people, other places, other times. An enormous gratitude welled up in me for the ritual kindness accorded the stranger. Me. During those hours I was never more a stranger and, uncannily enough, never more at home. That encounter was the first of many in my life that drove home the unsettling but inescapable fact that we are all strangers in this world, and that part of the elusive wonder of travel is that during these moments far away from all that is familiar, we are forced to face that truth, which is to say: the sacred truth of our soul's journey here on earth. This is one reason the stranger has always been held in awe, and why the stranger on the move is perpetually a soul in wonder.

Towards twilight, a stillness came over the Bedouins. The sun was setting below the long red line of the desert horizon. Silently, we watched while the tea simmered and the smell of cinnamon lingered in the air. It was a stillness that was there before the pyramids, a timelessness I hand't known until then that I had longed for. I felt utterly happy.

That afternoon of simple travel pleasures changed me. Farther down the road, over the next year of my travels which took me from Egypt through the Greek Islands and around Israel, Ahmet's respectful tone of voice resounded like a blessing. By naming my journey a pilgrimage, he had conferred a kind of dignity on it that altered the way I have traveled ever since. He had detected that I was at a crossroads in my life and seeking answers. With that kind of intention and intensity, my travels were moving question marks, as if journeys to ancient oracles. Each stage of my trek through the Mediterranean for the next year became imbued with the spirit of pilgrimage in which I was aware, as never before, of traveling back in time in search of the sacred, to places where the gods shined forth, to holy ground that blazed with meaning. I found it in the place I least expected; a few hundred yards away from famous tombs of Tutankhamen and Ramses VI, in the timeless shade of a Bedouin camp.

In the more than twenty years since that journey, I've traveled around the world, marveling both at its seven-times-seven thousand wonders, and at the frustration of fellow travelers I saw at those same sites, whose faces, if not their voices, cried out like the torch singer, "Is that all there is?"

I am haunted by the memory of an old friend who spent three days at Stonehenge, leaning against the megaliths, dreaming of Druids and King Arthur, and yet felt nothing. I remember meeting an Australian wanderer on the fifteen-mile hike through the Samaria Gorge in Crete who had been on the road for five years. He boasted of "taking in," as he put it, most of the world's monuments, then sighed the sigh of the world-weary. He hadn't really been impressed, he confessed, by anything, anywhere. "History is overrated," he concluded torpidly, as we reached the end of our hike. In response, he decided to live in a cave there on the beach for a few more years. I recall, too, the cruise ships I've lectured on and the passengers who never disembarked at Bali, Istanbul, Crete, or the island of Komodo, preferring to stay on board to play cards or watch old videos. Besides hearing a thousand complaints through the years by bored and disappointed travelers, I'm also aware of the spate of angst-ridden travel writers complaining we've gone from a world of classical ruins to sites simply ruined by too many (other) tourists. I am haunted by the memory of an old friend who spent three days at Stonehenge, leaning against the megaliths, dreaming of Druids and King Arthur, and yet felt nothing. I remember meeting an Australian wanderer on the fifteen-mile hike through the Samaria Gorge in Crete who had been on the road for five years. He boasted of "taking in," as he put it, most of the world's monuments, then sighed the sigh of the world-weary. He hadn't really been impressed, he confessed, by anything, anywhere. "History is overrated," he concluded torpidly, as we reached the end of our hike. In response, he decided to live in a cave there on the beach for a few more years. I recall, too, the cruise ships I've lectured on and the passengers who never disembarked at Bali, Istanbul, Crete, or the island of Komodo, preferring to stay on board to play cards or watch old videos. Besides hearing a thousand complaints through the years by bored and disappointed travelers, I'm also aware of the spate of angst-ridden travel writers complaining we've gone from a world of classical ruins to sites simply ruined by too many (other) tourists.

What strikes me about all these incidents is not my fellow travelers' cynicism or jadedness, but the way their faces and voices and words betray the longing for something more than their travels were giving them. Conjuring up their collective disappointment, I'm reminded of the statement I read years ago in the Irish Times by a Connemara man after he was arrested for a car accident. "There were plenty of onlookers, but no witnesses." In other words, we may log impressive miles in our travels but see nothing; we may follow all the advice in the travel magazines and still feel little enthusiasm.

Of course, the gap between ecstasy and irony in the realm of travel is a reflection of the abyss of experience in modern life. The phenomenon strikes at the core of this book. I don't believe that the problem is in the sites as it is in the sighting, the way we see. It's not simply in the images that lured us there and let us down, as in the imagining that is required of us. Nor does the blame lie in the faiths that inspire throngs to visit religious, artistic, and cultural monuments, as much as in our own lack of faith that we can experience anything authentic anymore.

With the roads to the exhalted places we all want to visit more crowded than ever, we look more and more, but see less and less. But we don't need more gimmicks and gadgets; all we need do is re-imagine the way we travel. If we truly want to know the secret of soulful travel, we need to believe that there is something waiting to be discovered in virtually every journey.

There are as many forms of travel as there are proverbial roads to Rome. The tourism business offers comfort, predictability, and entertainment; business travel makes the world of commerce go 'round. There is exploration for the scholar and the scientist, still eager to encounter the unknown and add to the human legacy of knowledge. The centuries-old tradition of touring to add to the social status endures, as does traveling to ancient sites for the sheer aesthetic "pleasure of ruins," as Rose Macaulay described it. In the seventeenth century there emerged the custom of the Grand Tour, which recommended travel as the last stage of a gentleman's education. Most recent is the phenomenon of the "W.T.," the World Traveler, renowned for drifting for the sake of drifting, and the "F.B.T.," the Frequent Business Traveler.

For each of these kinds of travel, there are more resources than ever. Bookstore shelves groan under the weight of guidebooks that cover major sightseeing in more than 200 nations around the world, custom regional guides for restaurants, cruises, architecture, gardens, ballparks, homes of famous artists and authors, guides for safe travel, and even a guide to the "most dangerous places in the world."

All of these roads to Rome are legitimate for different travelers, at different stages of life. But what if we are at the crossroads, as the blues singers moan, longing for something else, neither diversion nor distraction, escape nor mere entertainment? What if we have finally wearied of the paladins of progress who promise worry-free travel, and long for a form of travel that responds to a genuine cri du coeur, a longing for a taste of mystery, a touch of the sacred?

For millennia, this cry in the heart for embarking upon a meaningful journey has been answered by pilgrimage, a transformative journey to a sacred center. It calls for a journey to a holy site associated with gods, saints, or heroes, or to a natural setting imbued with spiritual power, or to a revered temple to seek counsel. To people the world over, pilgrimage is a spiritual exercise, an act of devotion to find a source of healing, or even to perform a penance. Always, it is a journey of risk and renewal. For a journey without challenge has no meaning; one without purpose has no soul.

*******

Over the years, I've participated in many traditional forms of religious pilgrimage, as well as modern secular ones, and trekked through the accounts of a wide range of travelers throughout history. I am convinced that pilgrimage is still a bona fide spirit-renewing ritual. But I also believe in pilgrimage as a powerful metaphor for any journey with the purpose of finding something that matters deeply to the traveler. With a deepening of focus, keen preparation, attention to the path below our feet, and respect for the destination at hand, it is possible to transform even the most ordinary trip into a sacred journey, a pilgrimage. In the spirit of the poet John Berryman, who reserved his severest criticism for "unobserved" writing, I don't believe tourism is the problem; the struggle is against unimaginative traveling. What legendary travelers have taught us since Pausanius and Marco Polo is that the art of travel is the art of seeing what is sacred.

Pilgrimage is the kind of journeying that marks just this move from mindless to mindful, soulless to soulful travel. The difference may be subtle or dramatic; by definition it is life-changing. It means being alert to the times when all that's needed is a trip to a remote place to simply lose yourself, and to the times when what's needed is a journey to a sacred place, in all its glorious and fearsome masks, to find yourself. Since the earliest human peregrinations, the nettlesome question has been: How do we travel more fruitfully, more wisely, more soulfully? How can we mobilize the imagination and enliven the heart so that on our special journeys we might, in the words of Louis Pasteur, "see everywhere in the world the inevitable expression of the concept of infinity," or notice, along with Thoreau, "the divine energy everywhere"? Or recall with Evan Connell the advice to medieval travelers: Pass by that which you do not love.

The earliest recorded pilgrimage is accorded to Abraham, who left Ur 4,000 years ago, seeking the inscrutable presence of God in the vast desert. His descendants, Moses, Paul, and Mohammed, embody the notion of sacred journeys. The Bible, the Torah, and the Koran, the holy texts of Hinduism and Buddhism — all admonish their followers to flock to the birthplaces and tombs of the prophets, the sites where miracles occurred, or the paths they walked in search of enlightenment.

We know of people as early as the fourth and fifth centuries leaving their villages to journey along the "glory road" to the Holy Land so that they might tread in the footsteps of Christ. By the eighth century, the first travelers were making the hajj to Medina and Mecca to make contact with sites made holy by the prophet Mohammed. Between the fifth and tenth centuries, the Irish made the turas, the circuit to the shrines of saints and ancient Celtic heroes. Besides religious pilgrimages, we have ample evidence of lovers of philosophy and poetry going to the shrines of classical writers in Athens, Ephesus, Alexandria, and to the tombs of Dante, Virgil, and the troubadours.

During the Middle Ages, going on pilgrimage to a holy site became an immensely popular practice and, in a way, was a forerunner of modern tourism. To help them on the long and often dangerous road to Jerusalem, Rome, Mecca, or Canterbury, medieval pilgrims often carried an inspirational book: a small Bible, a Book of Hours, even a literary classic such as the Illiad, or a work by Dante. Eventually, a kind of guidebook began to appear, such as the Marvels of Rome, which was immensely popular for the traveler and pilgrim to the ancient sites of the city. During the Middle Ages, going on pilgrimage to a holy site became an immensely popular practice and, in a way, was a forerunner of modern tourism. To help them on the long and often dangerous road to Jerusalem, Rome, Mecca, or Canterbury, medieval pilgrims often carried an inspirational book: a small Bible, a Book of Hours, even a literary classic such as the Illiad, or a work by Dante. Eventually, a kind of guidebook began to appear, such as the Marvels of Rome, which was immensely popular for the traveler and pilgrim to the ancient sites of the city.

For the ancient pilgrimage to the tomb of Saint James at Santiago de Compostela in northwest Spain, which attracted hundreds of thousands of pilgrims every year from the eleventh to the eighteenth centuries, travelers consulted an indispensable little book, simply called The Pilgrim's Guide. Thought by some to have been written by Pope Callixtus, whereas others believe it was authored by a thirteenth-century Frenchman named Aimery Picaud, The Pilgrim's Guide combined inspiration and useful references, and is now regarded as the prototype for modern guidebooks. Within its leather-bound pages were descriptions of the "sights, shrines, and people" that the traveler was likely to meet along the "pilgrim's road," along with prayers for safe journeys, lists of relics, architectural wonders, commentaries both kind and caustic about those one might encounter along the route, and a list of inns that welcomed pilgrims with complimentary meals and lodging.

In modern times, Lord Byron's Childe Harold's Pilgrimage was the "sacred" text for romantic poets traveling to Greece, while Mark Twain's Innocents Abroad served as a whimsical guidebook for the first generation of American travelers to Europe and the Holy Land. The sacred can also be exploited. On the nefarious side is the Book of Buried Pearls and of the Precious Mystery, Giving Indications Regarding the Hiding Places of Finds and Treasures, a manual of advice to looters, which contributed to the pillaging of Egyptian tombs.

In our time, Isak Dinesen's Out of Africa and Jack Kerouac's On the Road have stuffed the rucksacks of thousands of travelers who agree with Umberto Eco that it is electrifying to read about a place you've dreamed about visiting while actually there. The Art of Pilgrimage follows in the footsteps of the venerable "Pilgrim's Guides." It is designed for "crossroads travelers" — those who have the deep desire to make a significant or symbolic journey and need some inspiration and a few spiritual tools for the road. It is also for those who are frequent business travelers and holiday-makers who would like a few tips to make their journeys more memorable. At the heart of this book is the belief that virtually every traveler can transform any journey into pilgrimage with a commitment to finding something personally sacred along the road.

Today, the practice of pilgrimage is enjoying a vigorous revival, perhaps more popular now than at any time since its peak during the Middle Ages, when millions annually followed the pilgrim paths to thousands of shrines all over Europe. As part of the celebrations for the turning of the millennium, the Vatican declared A.D. 2000, "the Year of the Pilgirm." In a good tourist year, 3 to 4 million visit Rome; 50 million people (were) expected to descend upon Rome in 2000, to touch the relics and tread on holy ground. Today, the practice of pilgrimage is enjoying a vigorous revival, perhaps more popular now than at any time since its peak during the Middle Ages, when millions annually followed the pilgrim paths to thousands of shrines all over Europe. As part of the celebrations for the turning of the millennium, the Vatican declared A.D. 2000, "the Year of the Pilgirm." In a good tourist year, 3 to 4 million visit Rome; 50 million people (were) expected to descend upon Rome in 2000, to touch the relics and tread on holy ground.

From Ireland to Romania, Greenland to Patagonia, old churches, long in disrepair, homes of noteworthy authors and scientists, even torture chambers in St. Petersburg and Phnom Penh, are being restored or opened to lure tourists. Enterprising guides are leading hordes of literary pilgrims along the footsteps of the Beats in Greenwich Village, the Bloomsbury crowd in London, and the Lost Generation in Paris, so that they might feel the thrill of association with genius. Nature reserves in India for tigers, and in Africa for elephants, are being cordoned off and advertised as pilgrimages for lovers of the last bastions of wilderness. In Los Angeles, old horses carry the starstruck to the hotels and seedy bars where the famous and infamous died.

Truly, the phenomenon of pilgrimage is thriving, though it never really disappeared. Peel away the palimpsest of the glossy images of tourism and you'll find ancient ideas. Still, the question remains as vital as it has for centuries when pilgrims turned to priests, rabbis, sheiks, mentors, and veterans from the venerated path: How do we make a pilgirmage? Turn an ordinary trip into a sacred one? How might we use that wisdom to see more soulfully, listen more attentively, and imagine more keenly on all our journeys? Either while trekking to Mount Kailas, Mecca, or Memphis? Exploring a distant landscape, a famous museum, or a favorite hometown park? Are there lessons to be learned from great travelers, tasks to follow in the manner of true pilgrims, that can make sacred our travel?

Twenty-five hundred years ago, Lao Tzu said, "The longest journey begins with a single step." For those of us fascinated with the spiritual quest, the deepening of our journeys begins the moment we begin to ask what is sacred to us: architecture, history, music, books, nature, food, religious heritage, family history, the lives of saints, scholars, heroes, artists?

However, a caveat. "The point of the pilgrimage," as a Buddhist priest told the traveling author Oliver Statler on his journey around the Japanese island of Shikoku, "is to improve yourself by enduring and overcoming difficulties." In other words, if the journey you have chosen is indeed a pilgrimage, a soulful journey, it will be rigorous. Ancient wisdom suggests if you aren't trembling as you approach the sacred, it isn't the real thing. The sacred, in its various guises as holy ground, art, or knowledge, evokes emotion and commotion.

The Art of Pilgrimage is designed for those who intend to embark on any journey with a deep purpose but are unsure of how to prepare for it or endure it. As the title suggests, this book emphasizes the art of pilgrimage, which to my mind signals the skill of personally creating your own journey and the daily practice of slowing down and lingering, savoring, and absorbing each of its stages. This is a book of reminders and resources, literally designed to encourage what Buddhists call mindfulness, and what Ray Charles calls "soulfulness" — the ability to respond from our deepest place.

The book's seven chapters follow the universal "round" of the sacred journey, exploring the ways in which the common rites of pilgrimage might inspire modern equivalents for today's traveler. Like John Bunyan's famous pilgrim, the book progresses from The Longing to The Call that beckons us onward, then the drama of Departure, the treading of The Pilgrim's Way and beyond to The Labryinth and Arrival, before coming full circle to the challenge of Bringing Back the Boon....

As the Sufi mystic Mevlana Rumi wrote seven centuries ago, "Don't be satisfied with the stories that come before you; unfold your own myth." His poetic brother here in the West, Walt Whitman, put it this way: "Not I — not anyone else, can travel that road for you. You must travel it yourself."

Together, these musings aspire to the idea echoed in the work of seekers everywhere, that travelers cannot find deep meaning in their journey until they encounter what is truly sacred. What is sacred is what is worthy of our reverence, what evokes awe and wonder in the human heart, and what, when contemplated, transforms us utterly.

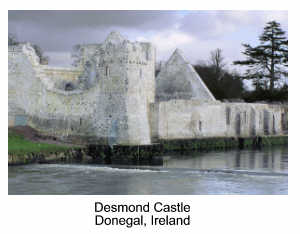

Surely, a voice whispered to me one night in the ruins of an old castle in Donegal, Ireland, surely there is a secret way. Surely, a voice whispered to me one night in the ruins of an old castle in Donegal, Ireland, surely there is a secret way.

The moon was rising like a celestial mirror over the heathered hills. The sea slapped at the peculiar basalt rock formations along the coast. The wind howled like Gaelic pipes. From a distant farmhouse came the sweet smell of burning peat.

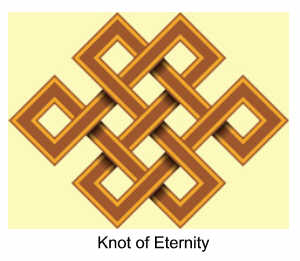

I stood shivering in the stone archway of an ancient chapel. Turning my head, I saw the weathered carving of a centuries-old Knot of Eternity. Each thread wandered far from the center, then whorled back in again. The ancient Celts believed this to be a potent symbol of life's journey, and the desire to return to the source that replenishes the soul.

Slowly, I followed the old stone path with my finger. Around and around went my hand, feeling the ancient chisel marks, the abrasions of wind, rain, and sun, and the tender burnishing of time. I thought of all the travelers who had come there, step by step, prayer by prayer, and wondered if they had discovered what they had been seeking, if their faith had be restored.

Slowly, the moon lit the ancient stone. The night air stung my eyes. My hand kept moving across the eternal knot, seeking out the hidden pattern beneath the whorling stone.

In that sublime moment I felt an ancient presence rise in my heart, and in my fingertips the unwinding spiral of joy.

This is the path that The Art of Pilgrimage follows, one carved out by the simple beauty of a handful of practices, tasks, and exercises that pilgrims, sojourners, and explorers of all kinds have used for millennia. In each of us dwells a wanderer, a gypsy, a pilgrim. The purpose here is to call forth that spirit. What matters most on your journey is how deeply you see, how attentively you hear, how richly the encounters are felt in your heart and soul.

Kabir wrote, "If you have not experienced something, then for you it is not real." So it is with pilgrimage, which is the art of movement, the poetry of motion, the music of personal experience of the sacred in those places where it has been known to shine forth. If we are not astounded by these possibilities, we can never plumb the depths of our own souls or the soul of the world.

Hearing this, let the voyage begin, recalling the words of the Spanish poet Antonio Machado:

Traveler, there is no path —

Paths are made by walking.

Phil Cousineau is a best-selling author, award-winning documentary filmmaker, photographer, teacher, and sports coach. He has published over twenty books, most recently Once and Future Myths: The Power of Ancient Stories in Modern Times Phil Cousineau is a best-selling author, award-winning documentary filmmaker, photographer, teacher, and sports coach. He has published over twenty books, most recently Once and Future Myths: The Power of Ancient Stories in Modern Times and Stoking the Creative Fires, and he has more than twenty film credits, including The Hero's Journey: The World of Joseph Campbell and The Future of the City: Reinventing the Urban World. His books include: The Hero's Journey: Joseph Campbell on His Life and Work and Stoking the Creative Fires, and he has more than twenty film credits, including The Hero's Journey: The World of Joseph Campbell and The Future of the City: Reinventing the Urban World. His books include: The Hero's Journey: Joseph Campbell on His Life and Work , Soul - An Archaeology - Readings From Socrates To Ray Charles , Soul - An Archaeology - Readings From Socrates To Ray Charles , The Art of Pilgrimage: The Seeker's Guide to Making Travel Sacred , The Art of Pilgrimage: The Seeker's Guide to Making Travel Sacred , Once and Future Myths: The Power of Ancient Stories in Modern Times , Once and Future Myths: The Power of Ancient Stories in Modern Times , and The Way Things Are: Conversations with Huston Smith on the Spiritual Life , and The Way Things Are: Conversations with Huston Smith on the Spiritual Life . .

Read more by Phil Cousineau at his website philcousineau.net

Return to Passages Menu

Subscribe to the Passages e-zine

|