|

Reading the Translucent Mirror:

A Reflection on Metaphors and Mythic Vision

by Jennifer Tronti, M.A.

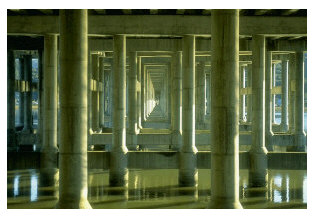

[Images: Hall of Mirrors, photographer unknown

Child Looking in a Mirror painting by Elizabeth Louise Vigée le Brun (1755—1842)]

Revelation through metaphor is a process of redirection, a bouncing backward of information between image and origin, between thought and action. Parallelism — evidenced in the mirror-like structure of metaphors and artistic creation — exposes the underpinning construction of mythic thinking, knowing, and expressing. Joseph Campbell wrote that the "endless mutations" (Gander 15) of the artistic remnants of mythic thinking, seen in sculpture, pottery design, or folktale as he discussed with readers of Flight of the Wild Gander , are like the layers within , are like the layers within a hall of mirrors where images are multiplied and refracted one upon the other. What can come from examining the visual dynamics concentrated around artistic endeavors which signify the physical manifestation of the metaphysical phenomena of myth? Campbell posited that "without images [...] there is no mythology" (Space xxii). This complexity of Campbell's summation of myth requires further scrutiny, for the mechanism of the eye — the literal and the abstract nuances of vision — connects the disparate characteristics of word and image. a hall of mirrors where images are multiplied and refracted one upon the other. What can come from examining the visual dynamics concentrated around artistic endeavors which signify the physical manifestation of the metaphysical phenomena of myth? Campbell posited that "without images [...] there is no mythology" (Space xxii). This complexity of Campbell's summation of myth requires further scrutiny, for the mechanism of the eye — the literal and the abstract nuances of vision — connects the disparate characteristics of word and image.

In his first chapter of Flight of the Wild Gander, "The Fairy Tale," Campbell described myth as "a picture language" (22). He further commented that "the folk tale is the primer of the picture-language of the soul" (Gander 25). The dichotomy between word and image, picture and language, accentuates and stretches taut the divisionary space out of which parallel constructs are possible. In speaking of the correspondence between symbol and meaning, Campbell reflected "that silence is where we are between two thoughts" (Gander 143). Meaning and representation give voice to larger webs or constructs; they act as verbal direction, pointing us "to." Speaking, however, negates silence. Silence exists as a liminal space, framed between one utterance and the next. The gap between idea and example — a metaphor — is silent. The gap between mirror image and physical image is silent. The gap between myth and meaning is silent. This silence infuses the realm which is "transparent to transcendence" (Space 34), but what does this mean? Understanding Campbell's notion of transparence and transcendence requires a new definition of sight.

In her pithy poem, "Mirror," Sylvia Plath's speaker, an anthropomorphic mirror, positions itself between the polarities of impenetrable objectivity and subsuming subjectivity. It speaks first as a thing which is "exact" and has "no preconceptions" (line 1); but it will later assert its sentience as a being which is "important" (line 15) and capable of faithfulness. Plath's mirror reveals the dilemma of transparency, that silent space. The mirror's human qualities articulate a yearning for a relational "looking at" rather than an unmindful "looking through." Thus, for the individual, mythic endeavors are not easy negotiations.

The overlapping and superimposed quality of the literal and symbolic nature of vision, which must be exercised and enacted simultaneously, asserts itself as the fundamental shock and toil of the mythopoetic project. The fullness of the symbolic vision is not readily unlocked until it has first employed, not an ordinary sense of perception, but a ripe awareness laden with a ruminative sensitivity. Ralph Waldo Emerson posits that "the poet" is "he whose eye can integrate all parts" (1108); this sense of poetic power is indicative of myth's power to revolutionize vision.

Artistic vision, seeing and perceiving on the level of myth, acts as a type of perceptual translation, but it is not conciliatory. This project of reformulation reconstructs by first tearing apart before bringing together. Myth rips apart formerly complacent or unmindful vision in order to reveal a new and radical configuration between reality and history. Defined as "religious recitations conceived as symbolic of the play of eternity in time" (Gander 7), myths revise any reliability upon the physical, material plane. The artistic eye perceives this new sensibility through a great fixation of purpose. Plath's mirror comments: "Most of the time I meditate on the opposite wall./It is pink, with speckles" (lines 6-7). Through this act of examination and meditation, the animated mirror declares: "I have looked at it [the wall] so long/I think it is a part of my heart" (lines 7-8). Through gazing with intent and purpose, the "object" and the "gazer" come into a new understanding. In The Inner Reaches of Outer Space , Campbell noted: "nature, as we know, is at once without and within us. Art is the mirror at the interface. So too is ritual; so also myth" (101). Observation and rumination can transform perception, and through this transformation a new relationship between myth and individual is birthed and bridged. , Campbell noted: "nature, as we know, is at once without and within us. Art is the mirror at the interface. So too is ritual; so also myth" (101). Observation and rumination can transform perception, and through this transformation a new relationship between myth and individual is birthed and bridged.

The basic optical dynamics of sight itself also shed a distinctive light upon the nature of myth. To begin, comprehensible human vision is physically possible through an inversion of images. The act of vision instinctually creates a sense of the world by reordering images to allow the viewer to interact with the environment. Campbell admiringly remarks that the Grimm brothers "never developed their idea" but "began with it full blown" (Gander 3). Not unlike the unimpeded power of sight, their methodology to approaching myth's "primer" is analogous to the very act of a functioning vision. For Campbell's notion of mythic images as "opening backward to mystery" (Gander xii), what is immediately perceived is only the first step in the mythic dynamic. Mythic-charged artistry seems to be vitally engaged in the translation between physical temporal existence and metaphysical eternal existence. When we begin to read the tales recorded and restored by the Grimms, with their wicked crones, their starved children, and their dark forests, we readers are thrust into a separate realm, yet one that finds accord in Campbell's writings. The basic optical dynamics of sight itself also shed a distinctive light upon the nature of myth. To begin, comprehensible human vision is physically possible through an inversion of images. The act of vision instinctually creates a sense of the world by reordering images to allow the viewer to interact with the environment. Campbell admiringly remarks that the Grimm brothers "never developed their idea" but "began with it full blown" (Gander 3). Not unlike the unimpeded power of sight, their methodology to approaching myth's "primer" is analogous to the very act of a functioning vision. For Campbell's notion of mythic images as "opening backward to mystery" (Gander xii), what is immediately perceived is only the first step in the mythic dynamic. Mythic-charged artistry seems to be vitally engaged in the translation between physical temporal existence and metaphysical eternal existence. When we begin to read the tales recorded and restored by the Grimms, with their wicked crones, their starved children, and their dark forests, we readers are thrust into a separate realm, yet one that finds accord in Campbell's writings.

Additionally, Campbell described the Grimms' project as an endeavor "to resurrect the present through the past" (Gander 3). The Grimms' folktales, not unlike the caves in Spain or France that Campbell later remarks upon, are "dangerous and absolutely dark" (Gander 76). By reading these tales, the participant is "immediately transported to the same visionary field. That mystery-dimension of man's residence in the universe opens through an iconography of animal [or in the case of folktale, elemental and magical] messengers" (Gander 76). Reading a Grimms' tale such as "Hansel and Gretel" or "The Girl without Hands," like entering these ancient caves, requires a similar kind of emotional stooping and straining, a wincing confrontation with the darkness of the world, without and within our spheres of touch, in order to reach a point of comprehension and communion as much with the like-minded as with the otherworldly.

The resemblance of myth's function to that of sight may be seen in its unconscious and thus perceived immediacy. Like the "full blown" ideas of the Grimm brothers, or the easy emergence of a dream, myth and sight share a rapidity of formation. After all, do we struggle to birth a dream or does it not frequently drop into view, Athena-like, full grown from somewhere within us? In his introduction to The Flight of the Wild Gander, Campbell established early on myth's right to proclaim itself a "natural phenomen(on)" (xii). "Mythology," Campbell commented, should be viewed "as a production of nature, serving, on one hand, the biological function of fostering a wholesome maturation of the psyche, and, on the other hand, the metaphysical, or mystagogic function of a Buddha-thing, 'thus come,' tathagata, opening backward to mystery" (Gander xv). This backward moving quality of myth, like optical inversion, owes its potency to its immediate and instinctual state. Campbell recognized this as the "native speech of dream" (Gander 22). He acknowledged a "parallelism of dream and myth" (Gander 33), and he further delineated: "the dream is the penultimate truth about the dreamer, of which all his experience is the temporal reflection" (Gander 34). Campbell spoke in the language of the mirror. Like Plath's poem, myth is both calm and "terrible" (line 18); the mythic mirror reflects and revises as it deflects and destroys.

Myth's action, akin to the "terrible fish" of Plath's poem, revolves around the forward thrusting motion of swallowing, which takes in, and the inward collapsing of drowning, which is overwhelming. Dreams, too, contain the ability to reflect the terror and beauty within individual and collective dynamics. Ignoring for the moment daydreams and fantasies, which can be linked to consciously manipulate artistic scribblings, dreams develop with a certain amount of immediacy. Their images appear "antecedent" to "meaning" (Gander xii). As landscapes populated with a variety of images spring unconsciously into view, dreams share a parallel connection to myth. The artist maneuvers these images emerging from a human and temporal condition and representative of a divine and eternal yearning. Campbell believed, "The artist sees with two eyes, and alone to him is the center revealed" (Space 117).

Myth and visual perception are sensitive to patterns and reflexive to context. Representation through metaphor and analogy, through compositional parallelism, is a mirror-like project, which illuminates, frames, and encapsulates the mysterious and ephemeral upon a "screen." However, this screen "swallows" as much as it shows. Meaning may be clouded, but the patterns are often left clearly visible. A king dies, a child is lost, a dragon is slain: seen through folktale's primer, myth delineates and enumerates visual and narrative patterns that organize and structure the range and periphery of our mythopoetic vision. "The oxymoron, self-contradictory, the paradox, the transcendent symbol pointing beyond itself, is the gateless gate, the sun-door, the passage beyond categories" (Gander 161). Campbell's "transparency of transcendence" exists in this pointing beyond self so that it is seen through and beyond and not at and to. The solidity of Plath's mirror's "opposite wall" is no longer speckled pink façade but a fleshy manifestation of meditation's transformative power over sight and relationship. Campbell underscores his own position by emphasizing James Joyce's comment that "any object intensely regarded, may be a gate of access to the incorruptible eon of the gods" (Gander 160).

Optical perception, too, is responsive to revision. The human eye can be trained: to sort variations, to gauge similarities, to perceive complexities. Similarly, "poets, prophets, and visionaries" (Gander 22) train our inner eyes. Picassos and Monets and Dalis can compel us to see a face or a landscape or an object beyond its surface details. Cubist, impressionist, and surrealist artists, through a process of inward and outward reconstruction, can revise our perceptions of past and present reality.

In the same paragraph that Campbell proclaimed "myth is a picture language" (Gander 22), he also cautioned that "the language has to be studied to be read" (Gander 22). Studied to be read: this is a matter of perception. We read, yes, but we must first see and in seeing perceive gradations of same, different, and varied. Our mythical vision must be sharpened before our mythical comprehension can be claimed. This passage from Campbell's chapter, "The Fairy Tale," lists figures from Dante to T'ai Tsung as the social and cultural revisionists of myth. Their revision began with an essential "brooding" upon the many manifestations of myth. This brooding, an act of deliberate internal contemplation, relies upon an internal perception of external ideas and images; myth and folktale become readable through an eye which has become sensitive and responsive to itself, its context, and the other.

Works Cited

- Campbell, Joseph. Flight of the Wild Gander: Explorations in the Mythological Dimension: Select Essays, 1944-1968

. Novato, California: New World Library, 2002. . Novato, California: New World Library, 2002.

—. The Inner Reaches of Outer Space: Metaphor as Myth and as Religion . Novato, California: New World Library, 2002. . Novato, California: New World Library, 2002.

- Emerson, Ralph Waldo. "Nature". The Norton Anthology of American Literature

, 6th edition, Volume B. Ed. Nina Baym. New York: Norton, 2003. 1106-1134. , 6th edition, Volume B. Ed. Nina Baym. New York: Norton, 2003. 1106-1134.

- Plath, Sylvia. "Mirror." The Bedford Introduction to Literature: Reading, Thinking, Writing

Ed. Michael Meyer. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin's, 2005. 828. Ed. Michael Meyer. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin's, 2005. 828.

Jennifer Tronti received her B.A. in English from California Baptist University and her M.A. from The Claremont Graduate School in English language and literature. She is currently a student in the Mythological Studies Ph.D. program at Pacifica Graduate Institute. She has been an assistant professor of composition and literature for seven years at California Baptist University. She lives in San Bernardino, California, with her husband and two sons. Jennifer Tronti received her B.A. in English from California Baptist University and her M.A. from The Claremont Graduate School in English language and literature. She is currently a student in the Mythological Studies Ph.D. program at Pacifica Graduate Institute. She has been an assistant professor of composition and literature for seven years at California Baptist University. She lives in San Bernardino, California, with her husband and two sons.

Return to the Mythic Passages Menu

Subscribe to the Mythic Passages e-zine

|